As this is again being discussed, I thought I’d bring it back to the top of the blog.

First posted July 2007, with a more personal follow-up here.

In the ‘I confess’ post, I said:

“I confess: that the idea of lay presidency appals me. It’s either a redundant aim (because communion is celebrated by everyone) or it’s simply an expression of immature and astonishingly impoverished theology. Priesthood is a differentiation sideways, not vertically, so what precisely is being objected to? I can’t see this as anything other than being haunted by a 16th century ghost.”

This has caused a bit of comment (off-line as well as on!) and it’s certainly something which is being discussed here in Mersea. So I thought I’d expand a little further. Click ‘full post’ for text.

This is still in the style of summary points:

– the role of the ordained minister is not ‘above’ the people, which would undermine the priesthood of all believers, but ‘alongside’ the people – separated out to perform a particular role on their behalf – if they were all one part where would the body be?;

– if a bunch of Christians were stuck on the proverbial desert island without an ordained minister, then clearly it would be good for them to celebrate together; it is the community gathered which does the celebrating (even when not on the desert island) – but I would lay odds that they would choose one person to do it, and not just take turns (unless they were already formed in that theology!) – NB there’s a thread in Lost that explores this, but I haven’t finished series 2 yet, so I don’t know where it’s going;

– a community celebrating because there cannot be an ordained minister present is very different from a community celebrating because they choose not to value what the ordained minister represents (ie unity with the wider church) – one is acquiescence to necessity, the other is an elevation of separation;

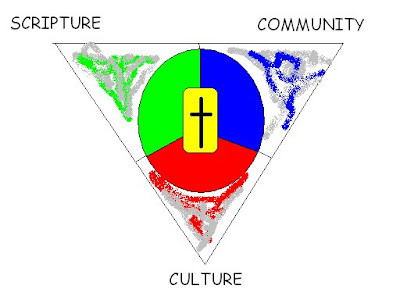

– it is precisely that elevation of separation which is the core problem with lay presidency, so far as I understand it, ie it is a mark of the local community gathering all authority to itself, saying to all outside their self-defined boundaries ‘we don’t need you’, whereas I see one of the essential tasks of the ordained minister as being to represent the wider church to the local community, and call it to account, not least through being the sign of fidelity to apostolic teaching;

– accepting ordained ministers is therefore accepting a wider church and all that that entails – it’s the definition of catholic, in its proper sense, and it’s the opposite of sectarian. It’s about being a part of something larger than the individual ego, or even a gathering of individual egoes;

– the task of the ordained minister is balanced – to represent the wider church to the local and vice versa – and the ordained minister is the one who has overall pastoral and teaching responsibility within a particular community – presiding at the eucharist is the function and sign of that authority, not the source of it;

– the ordained minister therefore also has important disciplinary functions – eg the excommunication of unrepentant sinners; the rooting out of bad theology – which cannot be delegated – or is this also included in ‘lay presidency’?!? I have visions of a church version of the grand Mexican Stand Off: ‘I excommunicate you!’ ‘No, I excommunicate YOU!’ ‘NO, I EXCOMMUNICATE YOU!’;

– of those whom I have met who advocate lay celebration, none actually want _anyone_ to do it, that is, they wouldn’t be happy if a stranger walked in from the street; nor even if some particular known members of the congregation performed the duty (for various reasons). Moreover, the idea that the person doing it should be trained up to do it is uncontentious – and this leaves open the real issue which is about the laying on of hands by the wider church, and the value of sacramental theology as such;

– in other words, what is being objected to isn’t the idea of some members of the community being allowed to preside rather than others, it’s the idea that being ordained by the wider church body represents something important – and so we are back to the idea of the local congregation being an authority unto itself, without any accountability to the wider church, either in space or time;

– at bottom, my strong reaction against this notion is a belief that it is yet another example of the idolatry of choice that has infected Western society, whereby each person is their own little God able to muster tributes according to their own taste (much the most insidious form of slavery) and where worship simply becomes an agglomeration of common preference, leading to the ten thousand things (denominations) rather than a unity with a Body much greater than oneself. I think this is one of the core things that identifies me as ‘Anglo-Catholic’ – though this is supposedly ‘whole-Anglican’ theology;

– I find great comfort in the idea that my ministry and authority does not rest upon meeting the particular standards of a local community but is bound up with the wider church as a whole (as signified by the laying on of hands). Without this form of acknowledged authority it seems that each congregation goes its own separate way, in smaller and smaller splinters, in more and more egotistical forms (even when the egotism isn’t exercised in a personal way, it is still a function of a theologically elevated egotism as such). One tyranny has replaced another (and the New Testament is hardly silent on the idea of ministerial authority). There seems to be no distinction between the idolatry developed in Western theology in the late Middle Ages, which separated priests from people, and the theology developed by the church – the same church that was inspired enough to put the Bible together – which progressively delineated who had authority to preside. Hence my comment that I see advocacy of lay presidency as “an expression of immature and astonishingly impoverished theology… I can’t see this as anything other than being haunted by a 16th century ghost.”

None of this is to say that an ‘agape’ isn’t something wonderful, and to be encouraged, eg in small group ministry, only to differentiate it from ‘Holy Communion’ – that foretaste of heaven which is the celebration of the catholic church, local and universal. The ordained minister is the sign of that wider unity. ‘Just’ a sign? Only in the sense that the bread is ‘just’ a sign of the Body of Christ! It’s not an accident that the idea of lay presidency is most closely associated with the least sacramental understandings of the Eucharist. If what happens in communion isn’t ultimately that important, then it’s not that important who presides – but if what happens in communion is a means of grace and essential medicine for the soul – then it’s much more important that it is done rightly. “For anyone who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment on himself” – and ‘the body’ here isn’t simply the bread, it’s also the communion of saints, in heaven and on earth.