Extracted from some notes for the PCC here in West Mersea. Our existing heating system has failed and we’re considering putting in a like-for-like replacement boiler – diesel at the moment, but we could shift to gas. (We remain committed to a greener system in the longer term, but the social costs of doing without heating, eg at weddings and funerals, are too much).

Peaking

The concerns I have centre around what is called ‘Peak Gas’, a variant of the ‘Peak Oil’ that I have frequently mentioned in meetings, talks and sermons. “Peaking” describes the moment of maximum flow of a resource, whether of oil or gas or any other non-renewable commodity. It tends to come at around the half-way point of extraction of the resource and so, by definition, there is as much of the resource left as has yet been exploited. In the case of both oil and gas this remaining resource is a vast quantity.. (I’ll use ‘billion cubic metres’, or bcm, as the units in this note.)

Given the inexorable decline of domestic production, not only will we be importing most of our natural gas needs in a very short period of time, so too will North America and the remainder of the EU.

Imports

So where will this imported Natural Gas come from? At the moment the EU imports its gas principally from Russia, and to a lesser extent from North Africa:

Through to 2020, however, there will be an increasing reliance upon newly established LNG imports, to the tune of over 200bcm.

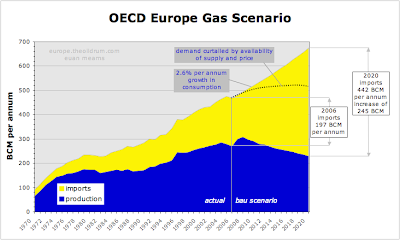

This assumes some demand growth, however, which may not be quite so plausible in the current climate! Another way of considering this, for the EU, is through this chart, which shows OECD Europe needing to import over 400bcm, from all sources, by 2020:

So where will the gas come from?

Russia

Although there has been some concern about the strategic viability of depending on imports from Russia, due to the ‘crisis’ in the Ukraine, it is in Russia’s own interest to be a dependable partner to the EU, not least because it is such a huge source of income. With the development of new gas fields to replace the more mature declining fields, it looks likely that Russia will be able to sustain her production capacity.

However, there are two other considerations. The first is that Russian internal demand for natural gas will be increasing over time, so, given static production, the amount available for export will decrease. More significantly, as other supplies to the EU decrease the competition for Russian supplies will become more severe. So, although Russian supplies to the EU are likely to be comparatively stable, ie amounting to the same quantity in 2020 as in 2010, they will become increasingly expensive.

LNG 1: North Africa

The second principal source for Natural Gas imports to the EU is from North Africa. Here there is some better news, in that increased capacity should raise the amount importable from this region:

Let’s be generous and say that through to 2020 up to 50bcm of extra import capacity is available from North Africa. This leaves some 350bcm to find.

LNG 2: Middle East

Along with Russia, the nations with the largest resources of Natural Gas are in the Middle East, principally Iran and Qatar, with Saudi Arabia having a little more. However, these vast quantities of reserves do not translate simply into a readily available resource. According to the EIA the export capacity of LNG from the Middle East, (around 200bcm now and mainly exported to the Far East), will be around 340bcm by 2015, rising to around 640bcm by 2030. This is one potential source of LNG imports to the EU.

Realistically there are no other sources of Natural Gas supply that could be imported to the EU. Whilst there are other Natural Gas sources (eg Indonesia) their supplies are both subject to peaking and already tied up in export contracts (eg to China and Japan). There are essentially two main LNG export markets, the Atlantic Basin (EU and Eastern US) and the Pacific Basin (Asia and Western US). What we are facing is a bidding competition between all the advanced nations for the increased LNG capacity from the Middle East; and even if the EU were able to completely win that bidding competition then there would still be a shortfall of around 200bcm each year!

What does this mean for the UK in particular?

This image, from 2005, shows where our government expects our gas supply to come from:

This picture is more than a little misleading in that it shows the capacity to import, rather than anything more concrete (worldwide LNG import capacity is around double the export capacity). What I would point out is that it also assumes that the UK can access the extra gas supply from Norway/Russia/LNG without giving any consideration to how realistic it is. If, as I believe to be true, a) Russian production is static and b) EU demand is static, then the gas imported from Russia is going to have to be obtained over the heads of an existing customer, which, again, will be expensive even if it is possible at all.

If we assume a demand for gas equivalent to today then we are looking at importing around 60bcm of gas; if we accept the government’s figure then we are looking at importing around 90bcm of gas needing to be imported. It is not at all clear to me where that gas is going to come from – even if the LNG capacity is developed in the Middle East according to plan, we are going to be bidding against other, richer nations for access to that gas, and there is not enough to meet the total demand.

As I see it the gas supplies will first become more expensive, as we rely on Norwegian gas and are only competing with other Northern European countries, and then the supply will become not just increasingly expensive but also scarce, as we start competing with the rest of Europe, the United States and Asia for access to a restricted resource. If I had to hazard a guess as to when these problems will start to become manifest I would suggest the 2012-14 time frame, as that is when Norwegian production is expected to have passed its peak. This is why I am concerned about our natural gas situation and why I don’t think it’s a good idea to commit ourselves to a gas supply for the next ten years.