Amidst all the national celebrations associated with a wonderful Olympics, I doubt that many people will have been following the financial news quite so closely. The Bank of England has indicated that it is going to continue with its policy of ‘Quantitative Easing’ (which is a technical euphemism for ‘printing money’). I’d like with this article to explain why that policy has not been working – and why it will not work – and link it in to an update on one of my perennial themes, of Peak Oil.

We live in an economy that has largely been dependent upon growing consumption. The more we spend, the more people are employed making things on which we can spend, and those employed people can spend their earnings on more such things, making more employment in turn, and so on. In other words, every pound that we spend then circulates in the economy and helps it to grow. Over the last several decades, this expenditure from earned income has been significantly supplemented by finance from another source – debt. So, if we imagine the economy to be like a balloon, what has happened is that, for a time, the air being blown into the balloon by our own lungs has been supplemented by air being blown in by an extra pump – and the balloon has therefore grown much further and faster.

The trouble is that this ‘over-inflation’ was a financial bubble, and the bubble has now burst. As a result of the financial crisis starting in 2008 the supply of credit into the economy – that is, the source of air from the pump – has been taken away. Worse than this, because the costs of that extra pump still have to be paid for, some of the air from our own lungs – that is, a significant part of our own spending power – is now being diverted from blowing up the balloon (growing the economy) to paying down accumulated debts. Those accumulated debts represent a hole in the balloon, and the balloon is not going to start being pumped up again until those debts have fallen to a more manageable level.

That is why the Bank’s policy of Quantitative Easting is not working, nor is it likely to. The extra money that the Bank is providing – which it hopes is going to enable the High Street banks to start lending again, and thus get the economy ‘blowing up’ once more – is simply being used to pay down and manage existing debt – that is, it is paying for the previous use of the extra pump, it is not actually pumping more air into the balloon itself. In other words, the Bank of England is engaged in a vast exercise of blowing air into a burst balloon, and that will be pointless until the balloon itself is fixed.

I am sceptical as to whether it is actually possible for the balloon to be fixed at all, and that is because of the impact of Peak Oil on our economies. Whilst the specifics of our present economic distress are all tied up with the financial world – the excess of debt most of all – what is not commonly appreciated is the role of energy in the economic system. That is, the great majority of previous recessions were triggered by an energy crisis, and our present on-going recession is no different. It was the massive run-up in oil prices beginning in 2005 that provided the pin which popped the balloon – and it is the continued high cost of oil which has placed a limit on how far the balloon of our economy is going to be able to grow.

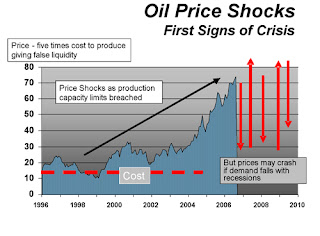

This is an image from one of the very first articles I read about Peak Oil, back in 2006, and I see it as one that has more and more relevance as we advance into an economic context dominated by expensive energy.

Notice that the oil price in 2006 was just breaching $70 a barrel – and that in 2008 it reached a high of almost $150 a barrel (it is presently $100-$120 a barrel, dependent on source). Each time the economy begins to recover, and demand picks up again – each time that air is pushed into the balloon – the price of oil will rise far enough to choke off that recovery. It is a simple application of supply and demand. According to the International Energy Agency Peak Oil – that is, the high-point of oil production – was reached in 2006. There has not been any significant increase in the production of conventional crude oil since then. The upshot is that we will never again have access to large quantities of cheap and easily obtainable oil. As the supply is fixed (and will diminish) the demand for oil can only be met by an increase in the price – essentially, the different economies of the world are bidding against each other for access to this commodity (the same thing will apply to gas, but with a 20-25 year delay, as Peak Gas will strike after Peak Oil).

So we are in a situation where we have two significant constraints on reviving our economy. The first is the residue of debt built up in previous decades, which will have to be paid down before the economy, in purely financial terms, is able to recover. The second is that we have shifted from an environment where energy was cheap and easy to obtain into one where energy is expensive and difficult to obtain – and we have only just begun to experience the implications of that shift.

Our best hope is that the economy is enabled to move sideways for a generation, and that during that time our political leadership takes the far-sighted decisions needed to position the country for the transformed economic environment that we shall be living in. There is a very great deal that could be done (in local terms it is called ‘Transition Town’)… but I’m not holding my breath.