Exhuming that Iraq post was revealing, in terms of how far my political perspective (on the Bush administration in particular) has shifted, and how much closer I am to embracing non-violence completely. Yet there is something that prevents me from going the whole hog – and in fact there is a part of me which has started to become suspicious that ‘non-violence’ is an idol. Here are some more or less connected thoughts, which represent a snapshot. The last paragraph is probably the most important.

A sincere embrace of the just war perspective would practically differ from a pacifist perspective in only a very small minority of cases. Most wars are unjust and unjustifiable.

Tim sent me an interesting link – here – which contains an interesting argument: “A second confusion in this argument is the notion that taking part in war shall be regarded as a lesser evil, rendered necessary by extreme circumstances. Such a claim has no part in traditional just-war theory—or, indeed, in any coherent moral theory.” This is exactly my perspective. It may well be true (though I doubt it) that it has no part in traditional just-war theory, but to engage in the discussion on those grounds would rapidly become academic and abstract. The intriguing question, for me, is whether it is true that this perspective has no place ‘in any coherent moral theory’ – because this I think is quite true, and it underlies why I chose the Bonhoeffer quotation this morning: “The knowledge of good and evil seems to be the aim of all ethical reflection. The first task of Christian ethics is to invalidate this knowledge.” This, I think, puts the finger precisely on the difference between a Christian perspective and a more conventional philosophical/ moral position. We live by grace.

Hauerwas’s argument (in The Peaceable Kingdom) about interrogating our imaginative examples is a strong one, but he doesn’t actually deal with the examples themselves – and the examples themselves are not abstract, but are real. So for the time being, I remain of the view that there are situations where I would resort to violence. This is an admission of sin, but I can’t see any way around it. Where things get awkward is when this perspective is shifted to a wider context, ie national or cultural. I remain of the view that Islamo-fascism is a radical evil, and one which if left unchecked will cause a tremendous pestilence to descend upon the world.

Yet is this just a question of lack of faith? That’s the issue that repeatedly nags at me. If I really believed in the overcoming of the world, I would not presume to judge the outcomes of decisions that might be made – I would simply obey the divine commands. For example, in pragmatic terms, I think that the Islamo-fascists have enough truth in their arguments to be heard sympathetically by most Muslims; I think that the Western world is sufficiently weak in material and spiritual terms that the eventual ‘victory’ of the West is not assured [[I’m a long term optimist there – I think the West will bounce back – but I think we have a darkness to work through first – and I don’t think we will be able to bounce back without addressing our cultural blind spot with regard to our Christian inheritance, in other words, without something like a revival]]; so it is not by any means implausible to me that the gospel could be eclipsed in the world; that the Bible could become a demonised text, that, over time, within a world-wide caliphate, the New Testament becomes something forgotten. Now I don’t believe that God will ever leave himself without witnesses, and I think Shia theology in particular has resonances that cross over into Christianity, so whether the Word becomes silent, that I don’t believe. But how far is the Incarnation repeatable? And does it threaten the church’s understanding of itself if it allows itself to die?

And what is the cost? Even if I was convinced of the long term triumph of the gospel against all odds (and I do believe in the long term triumph of the gospel in the hearts of all people) – does it really make sense to acquiesce to the fascists? And if we embrace a non-violent resistance against them, what does this mean when the fascists also embrace non-violent processes (eg democracy) to introduce something abhorrent (eg Sharia law)? Rowan Williams is fond of asking the question – and I think it is an extremely good one – “Who pays the price?” Is it legitimate, by my actions, to expect others (eg children) to pay the price? Or is there something here worth defending with dirty hands?

I am also starting to harbour a suspicion about non-violence, about whether it can itself take an idolatrous position within a theology. The Scriptures are violent texts; Jesus himself is angry and acts in ways that can be considered violent (Temple cleansing, obviously, but also violent speech acts); most of all, the violence of the world exhibited in the crucifixion is incapable of preventing God’s plans being accomplished. I do not doubt that violence is inherenty and inevitably sinful. My dispute is about whether it is always the MOST sinful option available.

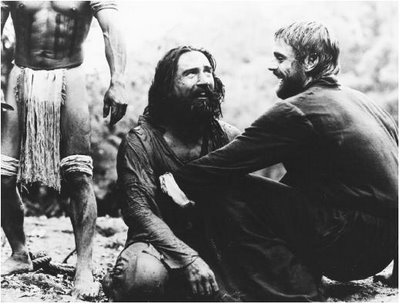

I am thinking an awful lot about two films. One is the Passion of the Christ, which haunts me, and was responsible for a significant shift in my attitudes. Watching Jesus exhibit non-violence was intimidating and inspirational. The second is the Mission, full of wonderful filmic imagery, and which throws up the fundamental choice at the end. Do you walk with Jeremy Irons behind the monstrance, or do you pick up your musket with Robert De Niro? I’ve always thought I’d be with De Niro (partly because my character is much more like the one he portrays in that film) but I am perennially disturbed by a sense that Irons is the one who shows faith. Yet the outcome of his faith is that the villagers are slaughtered.

There is a different way, I am sure. Not bound by pre-existing categories, into which we must fit our moral instincts. We can only ask ‘Lord, what is your will for me here and now?’ – and then seek to follow it, leaving any judgement as to merit in His hands alone.