“Work out what God is doing, and then get out of the way.” (Eugene Peterson)

Following that earlier discussion about music in the liturgy – see here and here – I thought I would set down a few thoughts about the new service that has taken root here at West Mersea, which may be worth sharing.

Firstly some background (taken from a paper I wrote whilst planning the changes in July of 2004). Within a month or so of my arrival in Mersea I began to argue for making the Eucharist the main service every Sunday (a return to the practice that had held with my predecessor but one – there had been an increase in the number of parishes in the benefice, which had provoked a change with my immediate predecessor, but I was taking a different view of things). Initially I was concerned that my understandings were not central to the Church of England, but were in fact extreme Anglo-Catholicism – and that I was therefore imposing my own understandings on a community for whom they would be alien. However, I did a fair bit of research on the mainstream Evangelical understandings of the Eucharist (see in particular this book) and was greatly reassured by what I found. Most pertinently, the first meeting of the National Evangelical Anglican Congress at Keele in 1967 adopted a resolution (following arguments led by John Stott) committing itself to ‘work towards the practice of a weekly celebration of the sacrament as the central corporate Service of the church’. As Colin Buchanan put it, “there can only be one top priority for all Christians. And it is communion. Any other service must fall into the category of helpful but not mandatory”. (This, by the way, was what led into my ongoing exploration of evangelical/reformed theology, which I knew very little about, but have found, on the whole, quite congenial. See this, written around this time.)

Anglican identity

Clearly, there are different congregations in a parish church, who attend different services at different times, and it is not the case that every service has to be exactly the same. What holds different congregations together, however, is a ‘family resemblance’ in terms of the overall spirituality; that is, each service is reflective of Anglican theology and understandings of faith.

In the preface to Common Worship is the following:

“The forms of worship authorized in the Church of England express our faith and help to create our identity… Just as Common Worship is more than a book, so worship is more than what is said; it is also what is done and how it is done. Common Worship provides texts, contemporary as well as traditional, which are resonant and memorable, so that they will enter and remain in the Church of England’s corporate memory – especially if they are sung. It is when the framework of worship is clear and familiar and the texts are known by heart that the poetry of praise and the passion of prayer can transcend the printed word. Then worship can take wing and become the living sacrifice of ourselves to the God whose majesty is beyond compare and whose truth is from everlasting.”

I see this preface as having a substantial amount of authority for the style of worship in the Church of England; that the normative style of worship is that described above, where “the framework of worship is clear and familiar and the texts are known by heart”. This places repetition – of structure and language – at the heart of the Church of England’s patterns of worship. In other words, it is through assimilating the patterns and prayers so deeply that they become unconscious that we are truly enabled to worship God.

CS Lewis made the same point in this way:

“As long as you notice, and have to count the steps, you are not dancing but only learning to dance. A good shoe is a shoe you don’t notice. Good reading becomes possible when you need not consciously think about eyes, or light, or print, or spelling. The perfect church service would be one we were almost unaware of; our attention would have been on God.” (C.S.Lewis, Letters to Malcolm, p.5)

“All Age Worship”

There was an existing “All Age Worship” (AAW) service, whose aim was meeting the needs of those members of the congregation who were in some way ‘disenfranchised’ by a choral eucharist. It is undeniable that this is a rich diet for those who are on the fringes of a church community (eg baptised but not confirmed, unchurched ‘seekers’ – call these ‘group one’) and those who are culturally distant from the dominant culture (young families, those who prefer more modern hymns – call these ‘group two’). Where AAW works is in ministering to these groups and enabling them to worship ‘in Spirit and truth’ in a way that is more natural to them. However, my concern was about the way AAW links together with that predominant form of service – I sometimes thought that AAW stood for ‘autonomous acts of worship’! – and also about the simple quality of the worship itself. There seemed to be no consideration given to where AAW was directed, that is, in what way was AAW functioning to bring people into the fullness of the faith – or was AAW presented as being an end in itself, with no call to those attending to move further? How was it linked with the broader church?

These issues did, of course, raise the question about whether the main service (choral and liturgical) should be as it was, or whether it should move in the direction that AAW had established. I felt that the answer to that question was different for the two groups identified above. Those in group one should be taught the truths of the faith, especially about the Eucharist, so that any and all obstacles which prevent them from full participation in the Eucharist are removed. Those in group two, however, represent the future worshipping life of the church community and so, to a significant extent, the “main service” will inevitably move in the direction that group two finds helpful in enabling right worship.

A community wounded by theological confusion

When I arrived in West Mersea I perceived a great deal of hurt surrounding the pattern of worship – lots of strong feelings and high emotion, a polarisation of views, and evidence of open conflict. AAW itself was the principal contested issue, with ‘battle lines’ drawn up for and against. Where something so central to church life is fought over, the church cannot be itself. It is prevented from giving praise and thanksgiving to God; it is prevented from an effective ministry within the local community. Such a wound, if unaddressed, destroys a church. I had never previously been exposed to a church where the basic parameters of acceptable worship were so contested, and so I saw addressing this problem as my overwhelming priority.

My first impression of the nature of the wound was that it stemmed from a theological confusion. This can be explained in the following way: in terms of the spectrum of Christian understandings, there are different emphases upon Word and Sacrament:

Far left – WORD ALONE

Left – WORD and sacrament

Centre – WORD AND SACRAMENT

Right – Word and SACRAMENT

Far Right – SACRAMENT ALONE

I see the middle three understandings as all falling within the broad church of Anglican theology. My concern was that a ‘far left’ theology had taken root, which saw the Eucharist not as a means of grace but as merely a visual aid, and hence the main thrust of my early teaching was on a right understanding of the sacraments, and a weekly parish communion being offered at 11am. However, I came to believe that I was at least partly mistaken in my initial analysis of the wound, for the situation was more complex. More important than the theological concern, in terms of the ‘heat’ of the debate, was a cultural one, which overlapped with the theological and caused great damage within the church community. The ‘group two’ that I referred to above were those who were culturally distant from the dominant culture of the main service, ie predominantly (but not exclusively) those of a younger generation. To try and put this across, I think we can use a scale of ‘Bible translations’:

A Authorised Version

B New International Version

C The Message

Christian communities evolve over time, and this is simply a way of trying to describe that process of evolution, from A through to C. (I am not wanting to explore questions of poetry or accuracy in Bible translations!) The AAW can then be placed as ‘Far Left – C’.

As I came to understand the wound in the Church, the polarisation and damage came from two communities who were talking past each other, who both (rightly) perceived something important to be at stake. Those who opposed AAW saw it as a ‘far left’ form of worship which had recklessly discarded Anglican theology and tradition. Those who advocated AAW were wanting to reject a suffocating formality which was seen as more and more culturally irrelevant and inhibiting. In other words, one group was arguing ‘left-right’, the other was arguing ‘A-C’. The problem as I understood it was rooted in an identification of these two differences, ie one about churchmanship, one about culture. I was led to believe that the way forward was to change the nature of AAW so that it fitted naturally into the ‘left’ or ‘centre’ columns, whilst retaining its position culturally.

Morning Praise

Hence I saw the way forward as the establishment of a new 9:30am service with the following characteristics:

- A stable liturgical structure – essentially CW Morning Prayer;

- To be called ‘Morning Praise’;

- To last approximately 45 minutes;

- To fit in ‘Left C’ on the grid above;

- Weekly provision (not monthly) to ensure stabilitas;

- Resourced with minister and organist, but not choir;

- Clearly understood as a supplementary ministry, pointing to the Eucharist.

It seemed to me that this would keep our centre of spiritual gravity in the mainstream of the Church of England; continue to minister to the majority of people who sought something like AAW; and provide a platform to grow in the way that a healed and healthy community should. Most importantly, I thought it would provide clarity about who we were as an Anglican church, and therefore be a base from which we could engage with our wider society and be provocative, without having our energies turned inwards in debates about worship.

One of the most important decisions that I made right from the start – and on which I expended much mental anguish and prayer – was a decision to include the Benedictus within the order of service. I had qualms that this would be seen as archaic, and would put people off. However, I also saw it as a core element of the service, one which maintained continuity both with the Anglican family of services, and, indeed, with deeper roots in Christian history going back to the Church Fathers. It was one of the principal elements preventing Morning Praise from simply becoming a ‘hymn sandwich’. I was therefore most reluctant to let go of it, and I asked a colleague with much expertise in the area to compose a new setting. I am pleased to say that this has worked extremely well, and the Benedictus has a settled place within the service.

Results

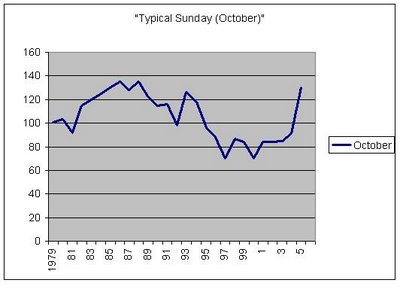

The service began on Advent Sunday 2004. The congregation was initially stocked with a ‘transfer’ of people from the 11am service, so that congregation dropped from around 85 people to around 65 people each week. However that 20 strong congregation has now grown to an average of more than 50 adults per week and, most importantly, we have seen children come back into church. At the service that I took eight days ago we had over fifty adults and some sixteen children – the first time that the congregation was significantly in advance of the 11am – and the Sunday School has shifted to this service to accommodate the need. Having said that, the 11am service is also beginning to find its feet, and numbers there, having gone through a trough – at one point hitting the low 50s – are now creeping back up past the 70 mark on a regular basis. This graph shows the results visually:

The graph shows 11am attendance for an average October in each year, and a combined 9:30 and 11am attendance for 2005. (2006 will be higher still, but not hugely – around the 150 mark.)

The graph shows 11am attendance for an average October in each year, and a combined 9:30 and 11am attendance for 2005. (2006 will be higher still, but not hugely – around the 150 mark.)

So what are the main factors behind this? Firstly, we undoubtedly benefited from the existence of a group of people who had been accustomed to the AAW and therefore provided an initial core congregation and ministry team. The most important factor that I would identify, however, related to the the benefit of particular expertise in two areas – the musical composition of the Benedictus, and the leading of music within the service itself. We made a decision early on to concentrate almost exclusively upon modern worship songs, ie those with a modern ‘rhythm’. This was seen as the form of musical expression that those coming into a church for the first time would be most familiar with, and would therefore enable this service to work as a ‘front door’ to the church’s life. As this was an area of church life with which I was markedly unfamiliar I relied upon the good taste and discretion of other members of the ministry team; fortunately we rapidly reached a consensus on what counted as ‘good’ (this book was circulated with great amusement).

In addition to the music, a significant aid has been the level of informality with which the service has been conducted. This, however, is perhaps the most important question, and deserves a section all to itself.

Tearing down the curtain

The service is deliberately ‘light’ in feel, even to the extent of there being banter amongst the ministers and between the ministers and congregation. This has led to the charge of the service being ‘irreverent’ which I have come to see as a) partly true and partly false, but more importantly, b) the partly true is a benefit not a loss. Let me explain. The sense in which ‘irreverence’ is partly false is that there are certainly elements of the service which are prayerful and reverent – especially the intercessions themselves, unsurprisingly enough. However, the ‘partly true’ is more interesting.

Jesus said that he would tear down the Temple and build up a new one in three days – referring to the establishment of the Church, His Body. The great symbol of Christ’s activity for me is the tearing of the curtain in the Temple, which destroys the barrier erected between the divine and the human, and thereby represents both the incarnation and the achievement of the incarnation – reconciliation between the human and the divine.

More subtly what this means – and what I am now beginning to properly recognise – is that Jesus is shifting the locus of worship. The Temple form of worship is vertical and hierarchical, with God at the summit. Jesus says, wherever two or three gather in my name, there am I in the midst. The form of worship – most supremely exemplified in the eucharist – is now horizontal, a gathering. God is immanent, incarnate, in the midst. Transcendence is still there but it has been transformed, reshaped, in line with Christ’s intentions. We see the image of God in our neighbour, the face of Christ in the person whom we are alongside.

‘Reverence’ seems so often to mean a desire for vertical worship, what we might think of as Temple worship – a holy of holies, towards which mere mortals should fear to venture. In practice, what happens is that the vertical worship becomes a barrier – it is a replacing of the curtain. Where once there may have been priests and temple guards preventing an approach to the divine, now there are different cultural forms. This is why I see an embrace of contemporary music (the best of, not the entirety of) as being wholly in line with both the Reformation impulse and indeed Christ’s own example and teaching. Worship of a form that is ‘understanded of the people’ (Article 24 of the 39 articles). Embracing contemporary music now seems simply a refusal to replace the curtain.

Where does this leave mystery? For I do retain a view that mystery is essential, ‘mysterium tremendum et fascinans’ – and God cannot be wholly domesticated. Yet our sacred mysteries are the sacraments; it is sacramental worship where a sense of mystery and awe is most necessary – and yet, even there, if we understand the eucharist aright, what greater mystery can there be than the face of God revealed in a human being, in a neighbour?

Conclusion

I began with the quotation from Eugene Peterson which represents my thinking on the 9:30 service, for the simple reason that my dominant impression is of ‘getting out of the way’ of something which God was bringing into being here in Mersea. God is always present and active – the gifts of many people have been brought together to shape the service, and to make it into the success which it has become. It would be fair to say that it has exceeded our expectations; that the congregation continues to grow both in numbers and spirituality – indeed, several members were recently confirmed. Although it is a small service, in a small corner of Essex, I do see the flourishing of this plant as a sign of hope for a church too often weighted down with a sense of failure.