My journey from the first book to the second…

My earliest recollection of an environmental awareness dawning in me was when I was reading an Enid Blyton book, the name of which I cannot now recall – I must have been aged around seven or eight years old. It wasn’t one of the Five or Seven sequences, but within it there was a description of some children playing in the outside, beyond a wood, a long way from home (something that I did a lot in real life) and coming across some rubbish that had been left. I think it was paper wrappings rather than anything more foul, but from memory Blyton talks about the way in which the rubbish would remain, marring the environment. That situation struck me as a wrongness; this wasn’t an argument, just an instinct, a seed.

That seed only really started to grow after I had left school. First, and fundamentally, reading Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance helped me to put that instinct into a wider context. In particular, I still often find myself remembering a scene where Pirsig and his son cross over a highway, and look down on a traffic jam. The contrast between those two experiences of technology has always resonated with me; that is, I am fully convinced that the Buddha can be found within the pistons of an internal combustion engine! The point is to make the technology serve the human, not to conform the human to the Machine.

At University my understanding of the green perspective properly started to broaden out. Amongst many other books I was particularly influenced by Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Jonathan Porritt’s Seeing Green. This was also when I read The Limits to Growth; whilst I found that analysis plausible on an intellectual level, it didn’t grip me in the way that the other books did. For me being Green was about living in the world in a certain way, with a certain set of virtues and with a view towards harmonious and community-centred living (I was also getting to grips with liberation theology at this point). I wasn’t particularly politically involved (the reasons for that are a story for another time) but I remember knocking on doors and campaigning for Mike Woodin at one point.

When it came to deciding what to do after graduating I was tempted by academia – I have always been tempted by academia – but the lure of earning a living was stronger. Most of the commercial options had no appeal and I chose to further my environmental awareness by joining the Department of the Environment. Here I was involved right at the sharp end of environmental debate from the beginning, as my first job centred on the safety of nuclear power! Although the postings were only supposed to be for a year, my first one was extended in order for me to run the ‘THORP consultation’, which was fascinating, and I got to see green politics from the inside, both how decisions are made by No 10 and the Cabinet, but also how the external bodies and campaigning groups made (or didn’t) any impact (without going into details, I was massively more impressed by Friends of the Earth than by Greenpeace).

Whilst I stayed in the DofE for a few more years, and learned an immense amount, in 1995 I got ‘clobbered by God’ and my attention turned to vocational matters. All matters green started to take a back seat, and after much change and moving around, it was only in 2005 that I started to look again at environmental concerns. This was triggered by reading an article by Bryan Appleyard that introduced me to the issue of Peak Oil, and this became an abiding passion for me. From working on the nuclear industry I had developed some awareness of questions around power supply, and I remain very interested in questions around energy.

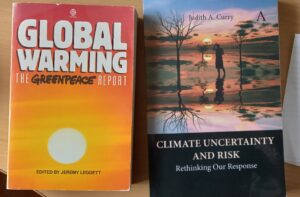

So this reawakened me to the analysis offered by the Limits to Growth perspective (Peak Oil is simply one facet of that, albeit, for me, the most salient) and my dormant green concerns now started to wake up again. At this time – as had been the case ever since I became aware of the issue after Thatcher’s speech in 1988 – I accepted the mainstream consensus around what was then called global warming. That was when I bought the Jeremy Leggett book illustrated at the top (in 1990). What I want to sketch out now is how I became more and more detached from that consensus, and now regard it as a bad religion, a form of insanity.

The first knock came when in 2007, via the excellent (sadly now moribund) website The Oil Drum, I came across the work of David Rutledge. Rutledge pointed out that the IPCC estimates for available fossil fuels took no account of the ‘Peakist’ perspective (peaking applies to all the fossil fuels, not just oil), and that the most alarming models were radically unrealistic. This was a surprise to me. As I found the scientific understandings around resource limits persuasive and ‘hard’ (ie grounded in solid data) this meant that there was, for the first time, a question mark against the IPCC. I was working on my book at this time, and I wasn’t sure whether to use as the precipitating challenge global warming or peak oil; discovering Rutledge’s work made the choice very easy.

More radical was the impact of Climategate in November 2009. The IPCC not taking the Peakist arguments into account I thought was a simple mistake, that would be corrected over time – an innocent assumption on my part. Climategate persuaded me that there were bad actors involved, Michael Mann foremost amongst them. As this was deeply challenging to my preconceptions I felt the need to dig into the details of this (and learned a lot about paleo-climatology in the process) and I particularly benefited from Andrew Montford’s writings. I go into some detail here, but the gist of my conclusion was simply that a) the Hockey Stick is very bad science, and b) the perpetuation of the Hockey Stick was not driven by scientific considerations but by social and cultural ones. I am persuaded that the understanding of historic temperatures that prevailed before the malign Dr Mann got involved is essentially correct, ie that there were previous warm periods in human history that reached higher temperatures than we now face (Minoan, Roman, Medieval warm periods).

This was an uncomfortable time for me in many ways. I remained (so I thought) within the overall environmental, green worldview, I was just more and more persuaded that the greens were making a great mistake in placing all their emphasis upon climate questions. I read a lot by people on all sides of the issue at this time, from Watts Up With That to Real Climate, and my principal take away was that reasoned argument was being lost beneath the politics, that is, the ‘scientific consensus’ was being enforced by social pressure and force – by bullying. The science simply wasn’t strong enough to win arguments on its own, so unethical behaviour had to be relied upon to make up the difference. Round about 2011 or so I settled on one main person to follow, who had earned my trust as someone who took a genuinely scientific approach to these questions: Judith Curry at her Climate Etc blog, and she is also interested in the philosophical aspects, which are my bailiwick. I still read a handful of others (Steve McIntyre, Roger Pielke) but I have stepped away from following all the detailed arguments.

Whilst I am open to further arguments on the technical questions, it is the wider sociological aspects that interest me now. I am persuaded that the present noise is essentially a bad religion, a conclusion that I had reached before coming across this book (which I have purchased but not yet read). When truth becomes subordinate to political questions, and those questions are shaped and structured by prior political interests, then the scientific discussion is compromised by human nature. That is, as I have argued more substantively elsewhere, good science is a subset of good religion. It is impossible to carry out good science without the context of a robustly embedded good ethic (= it is bad to falsify research), and that good ethic cannot subsist without a grounding in a religious, narrative framework (= ‘this is why it is bad to be bad’). It is not possible to be a good scientist without a sense of holiness (and, I suspect, it’s not possible to be a good scientist if your metaphysic is antithetical to the Christian worldview – I might go into that more on another occasion).

Why does this matter? For all my life I have had what I would now call an environmental concern, and I have often been either a member of the Green party, or a green member of another. I still think of myself as ‘green’, but what I see in the present Green movement seems insane, and not just about environmental questions. So in part, I wanted to tell this story in one place, so that I can refer to it in future. I sometimes think of myself as ‘a deep green climate sceptic’ – I remain convinced that we are in a state of overshoot, I’m sympathetic that we might be in an olduvai gorge situation, and we certainly have to reckon with the nature of the one-time ‘carbon pulse’ (we will go back to coal as we descend the down-slope). In particular our general cultural conversation is ‘energy blind’; most especially the ways in which, even now, investment in renewables is dependent upon the ready availability of fossil fuels, especially diesel, and the way in which our economy is influenced by the availability of oil (which was the underlying cause of the 2008 financial crisis). From my point of view the attention given to climate change is a great green herring.

This is slowly becoming obvious. When the bad science is only (literally and metaphorically) in the stratosphere, the ordinary person quietly ignores it. Now that it has triggered the idolatry of Net Zero it is beginning to impact upon most people’s daily life. When it gets to the point of saying ‘you must not heat your home because of climate change’ resistance gets stronger and the standard of evidence that the science has to meet becomes much more important. As that evidence doesn’t exist, the modern green movement is about to have its very own ‘Wile E Coyote moment’ and be left behind. Pointing out that the climate is changing is not enough (it clearly is); even pointing out that human activity is involved in that change is not enough (our behaviour does have an impact). It is the catastrophising which is the bad religion – and bad religion can only be overcome by good religion, not by the absence of religion at all.

Which is why, in the end, I’m a Christian not a green.

Here I stand, I can do no other; God help me.

You must be logged in to post a comment.