Ben Myers has been hosting a sequence of ‘why I love…’ This is my offering.

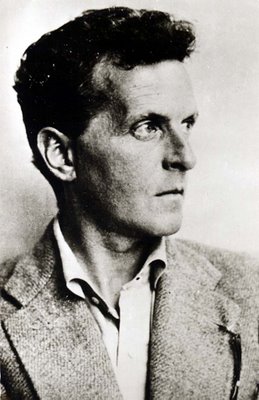

“If what we do now makes no difference in the end, then all the seriousness of life is done away with” – a remark which Wittgenstein made to his friend Drury, skewering the universalist heresy. Wittgenstein was a deeply serious man, and I believe he developed insights which all theologians need to absorb. Whilst it is debatable whether he was in fact a Christian, he certainly believed in God, and infamously saw things ‘from a religious point of view’. Whilst at service on the Eastern Front in WW1, he was known as ‘the man with the gospels’, as he never went anywhere without taking Tolstoy’s summary with him. He was a rather tortured soul in terms of his sexuality, he revered Augustine (the biggest influence on his own thought – he felt the Confessions to be “the most serious book ever written”), he hated virtually all modern music (you could “hear the machinery in Mahler” for example) and he gave up all his wealth to his sisters, as he felt that they were the only people unlikely to be spoiled by it. Clearly, in a different era, he would have been a monk, possibly a hermit. I find him a compelling human being: complex, flawed, yet gripped by the claim of the divine upon his life.

What is most important about Wittgenstein intellectually is his method of philosophy, which prevents a fruitless pursuit of metaphysical ‘solutions’; more precisely, it teaches us what metaphysics actually is. As such, Wittgenstein’s method is a necessary discipline for theologians, as it prevents us from mischaracterising the nature of Christian doctrine. As he put it himself “Christianity is not a doctrine, not, I mean, a theory about what has happened and will happen to the human soul, but a description of something that actually takes place in human life. For ‘consciousness of sin’ is a real event and so are despair and salvation through faith. Those who speak of such things (Bunyan for instance) are simply describing what has happened to them, whatever gloss anyone may want to put on it.” Wittgenstein has had a great influence on contemporary theology, from Hauerwas to Herbert McCabe, and it seems to me to be a wholly beneficial one.

Whilst most understandings of Wittgenstein do emphasise the ‘Sturm und Drang’ of his life, I think there is a generally underappreciated current of joy. He used to relax by going to the cinema, especially enjoying Westerns – and he found this to be of value. He wrote early in 1947, ‘I have often learnt a lesson from a silly American film’ – and I believe that he watched something that year which gave him some inner peace, that allowed him to believe that his life was worth something after all. After all, his last words were ‘tell them I’ve had a wonderful life’. I like to think it was what he had in mind.