Our organist is dipping his toe into the world of blogging…

Do go and say hello and reassure him that the blogosphere is full of nice, charitable and sane people 🙂

Our organist is dipping his toe into the world of blogging…

Do go and say hello and reassure him that the blogosphere is full of nice, charitable and sane people 🙂

He wrote me a prescription. He said “you are depressed,

But I’m glad you came to see me to get this off your chest.

Come back and see me later – next patient please!

Send in another victim of Industrial Disease.”

One of the insights that I have found helpful whilst pursuing psychotherapy is the realisation that I was struggling with something that, at least potentially, has a label. At the moment my therapist and I are calling it “depression”, although I’m digging down into it more deeply at the moment, as I think there is more to be discerned, and I think ‘burn out’ may be more accurate. (For what it’s worth, my therapist agrees that whatever it is, I’m not depressed at the moment – thank God, my CME adviser and my Bishop for my sabbatical.) That is, as discussed on this blog before, I think I was/am burnt out by the pressures of ministry in this place.

From “Time to Heal”:

Burn-out in carers

This is a syndrome of physical, spiritual and emotional exhaustion that is particularly likely where there is an experience of discrepancy between expectation and reality.

Three stages of burn-out have been described:

– In the first stage there is an imbalance between the demands of work and personal resources, which results in hurried meals, longer working hours, spending little time with the family, frequent lingering colds and sleep problems. This is the time to take stock, seek God and the advice of those around us.

– The second stage involves a short-term response to stress with angry outbursts, irritability, feeling tired all the time and anxiety about physical health. This stage highlights a real need to get away from it all.

– Terminal burn-out, stage three, creeps up insidiously. The carer cannot re-establish the balance between demands and personal resources. He or she goes into overdrive, works mechanically, by the book, lacking the fresh inspiration of the Holy Spirit. They tend to be late for appointments and to refer to those they are caring for in a derogatory manner, using superficial, stereotyped, authoritarian methods of communication.

On an emotional level, the carer becomes exhausted, incapable of empathy and overwhelmed by everyday problems. Emotional detachment becomes a form of rejection, which can develop into irritability and even aggression towards those nearby. Persons in this situation put themselves down, feel discouraged and wonder how they ever achieved in the past. Problems pile up and paralyse the mind. Disorganisation results in more precious energy being expended to make up for lost efficiency. Fatigue deepens and thought processes slow. Physically, an inner tension, an aching across the chest, weakness, headaches, indigestion and a lack of sleep are often experienced.

The caretaker was crucified for sleeping at his post

They’re refusing to be pacified it’s him they blame the most

In retrospect I can see various symptoms quite clearly, not least, for readers here: fewer blogposts, dropping off my beach photos, stopping the Learning Church programme and, frankly, growing my hair (= not paying attention to taking care of myself). I think there were specific tensions causing a problem – some of which I have taken action to address, and I’m optimistic for the future there – but the fundamental one is one of workload.

The maximum size of congregation:priest

On ITV and BBC they talk about the curse –

Philosophy is useless, theology is worse.

History boils over, there’s an economics freeze,

Sociologists invent words that mean ‘Industrial Disease’

I read in many places that 150 people is the practical top limit for a congregation to be manageable for a single stipendiary priest. Bob Jackson calls this the ‘pastoral church’ and the minister is thereby the key to how far the congregation grows or flourishes, for better or for worse. It ties in with sociological and anthropological research suggesting that 150 people is a universal human limit.

One aspect of this is that, unless steps are taken to directly address this problem, congregation size is independent of surrounding population. Beyond a certain point, increasing the population will not affect the size of the congregation as the glass ceiling will remain in place. This, I think, is the primary driver for my burnout:

Trouble is, whenever I raise this topic in formal meetings like the Deanery Standing Committee, people’s eyes tend to glaze over with a ‘here goes Sam again’ expression. It’s true that there are some mitigating factors, not least a significant number of retired clergy, but to my mind that doesn’t address the point. To my mind it is more about a different model of ministry being employed – one aspect of Herbertism which we could call ‘establishment’.

This is not a novel insight. Bob Jackson has discussed it in great depth in his books and given what I think is quite a compelling analysis. If we accept the establishment model then local population becomes the most significant factor – and the clergy are then deployed ever more thinly. Given the glass ceiling of 150 as a maximum size of congregation per pastor this approach guarantees further decline. The alternative model would be to reinforce patterns of growth – but that involves a profound culture shift away from the establishment pattern. This raises the shade of ‘congregationalism’, but that seems bizarre to me. After all, TEC is still episcopal isn’t it??

“Part of the trouble is that the Church of England’s ‘managers’ have in many cases committed themselves to a model of ministry which denies that the clergyperson is ‘chaplain to the congregation’. Ministry is conceived as being to the ‘whole parish’, and since need is seen in material terms, a large parish in a deprived urban area is defined as more ‘needy’ than a small parish in a well-off rural area.” (I wrote about a related aspect here)

The trouble is that what has happened to me is in the process of happening to all the other clergy too, as we start to wrestle with the impact of ‘downsizing’, ie industrial disease. The overwhelming majority (95%+) of clergy that I know are already overworked. I think it is a truism that the potential work for a priest is infinite, and as priests tend to be conscientious, there is an inbuilt tendency towards overworking and exhaustion. This is reinforced by masochistic minister syndrome, by which, unless a priest is suffering, they don’t feel that they’re doing their job properly. And, of course, George Herbert has something to do with it.

What this also means is that, in a context where virtually every priest complains (legitimately) about overwork, there are no commonly agreed criteria on what constitutes an excessive workload. How do you compare and contrast a job with several PCCs to a job with several CofE schools? Inherent in any discussion is the question of what model of ministry is being favoured and, therefore, questions of churchmanship are not very far away and liable to erupt (invariably unhealthily IMHO).

Trouble is, if the various Diocesan authorities don’t take a step back and resolve to make some very fundamental decisions then to all practical purposes mission and ministry will collapse in the CofE. I would distinguish this from “keeping the show on the road”, and keeping services going. I don’t see any need for those to stop, as that doesn’t require full-time ministers to maintain – and I wouldn’t want to underrate how important that is – but if your vision of church is seven days a week then you cannot be happy with that. In other words, are we simply about ‘managing the decline’ – thereby doing many things wrongly in my view, not least destroying a great many stipendiary clergy – or can things be done differently?

The further problem of bigness

Two men say they’re Jesus – one of them must be wrong

If we carry on the way that we are going, then all full-time ministries will look like Mersea. There are consequences to this. The first, rehearsed ad nauseam in George Herbert discussions is that the priest is no longer a pastor but a manager. Yes, managerial work is still pastoral – and if the management is not conducted in a pastoral manner then all sorts of havoc follows – but I can’t help feeling that there is a gap between what is envisaged at ordination and what actually follows on in practice.

This is not necessarily wrong, and it may well be of God. The Church seems to be more or less consciously adopting a model whereby priests are placed on to one of two tracks: a full-time stipendiary track, with associated full-time training, with the eventual destination of exercising ministerial oversight over parishes; a second, part-time, associate priest track, emphasising the pastoral (dare I say Herbertian) model of priesthood. I don’t have much of a problem with that – I can see that it makes all sorts of sense and I can see that this may be what God is calling us to pursue – I just can’t escape a sense of mourning. This is an ongoing issue for me – of actually wanting to be part of a congregation where I know, not just everybody’s name, but have some sense of where they are with God at the moment. Life would be much easier if I didn’t care so much.

Some more John Richardson: “The fact is that if the clergy of the future are to be team leaders, they must also be allowed to be team managers, and this means being allowed independence to exercise local initiative, authority to commission local leadership and financial control to fund what they propose doing.”

In one sense, the answer that the church is being called to affirm is that of the priesthood of all believers, understood not in the ‘fighting a 16th century ghost’ sense of advocating lay-presidency, but in the sense that all the baptised have a common vocation to ministry. The trouble is that in large agglomerations there is much more room for people to be passengers.

“Once anonymity is possible, the church ceases to be a community of followers of Jesus.”

Subsidising our own decline

Meanwhile the first Jesus says ‘I’d cure it soon:

Abolish Monday mornings and Friday afternoons!’

The other one’s out on hunger strike he’s dying by degrees.

How come Jesus gets Industrial Disease?

Related to this are all the questions about parish share. I don’t have any disagreement in principle with the transfer of monies between different Christian churches, it’s just that the present system seems to take away all discretion from the parishes themselves. Do the central authorities believe that, without a parish share system, Christians would not wish to fund missionary work? The real trouble is that – as Bob Jackson (him again) has identified – the existing system is a socialist system. Not (chance would be a fine thing) socialist in an Acts of the Apostles sense, but socialist in a Stalin-knows-best sense.

What this means, in practice, is that those parishes which are able to grow and develop are deprived of the resources with which to sustain that growth, and end up falling back. Whereas, those parishes which have found a comfortable spot (eg the 120 members mark) will continue to be subsidised and supported no matter what happens in terms of mission.

If I sound a little bitter it’s because I think that’s a good description of what has happened to the Mersea benefice.

Surely at some point the powers-that-be will wake up and discern that the present situation isn’t simply unsustainable but that it is unChristian too. We are pouring all of our resources into maintenance, aka genteel decline, when in fact we need to be engaged in a much more bracing embrace of mission.

Bob Jackson, in his book ‘Road to Growth’, spends several chapters describing the problems associated with the parish share system. He summarises them in these bullet points:

“In conclusion, the whole chaos of quota, parish share, or common fund systems is simply not serving the church well.

1 It is inconceivable that every diocese, with its own unique system changing every few years, has currently found the best possible one, or even a good one;

2 Systems risk provoking conflict and dishonesty. They can lead to more serious division;

3 They do not provide a secure and stable framework in which churches can do long-term planning;

4 They fail to provide the fairness their architects desire;

5 They absorb the best energy, time and expertise of diocesan leaders and officials. They divert people at every level from concentrating on the real ministry and mission of Christian churches;

6 They asset-strip the large churches and tax away the growth of growing churches. They encourage the declining and sleepy in their ways;

7 They encourage false judgements to be made of clergy and endanger the future provision of dynamic senior leadership;

8 They cannot cater for fresh expressions of church;

9 They fail even to maintain the current levels of parochial staffing, let alone to produce the resources for growing the new sorts of expression without which the Church may wither away.”Jackson recommends a solution incorporating the following elements:

1. Churches pay the costs of their own ministers

2. Fee income stays with the local church

3. Diocesan costs are shared by local churches

4. The total bill (1&3) is presented to each church each year, and published in the church accounts.

Essentially what Jackson proposes is a way of a) localising the process; b) making the system completely transparent (and therefore much more defensible); and c) restoring the relationship between those who give and those who receive. I can’t see the powers that be choosing to shift to this system, but it will come – not least because the Transition process will dictate it.

Still pursuing my own vocation

There are times when I get gloomy about the present situation. I find this quotation useful: “Francis Dewar identifies three vocations which, he maintains, can often become confused. Our primary vocation is to know God, it is the call to basic Christian discipleship. Our second vocation is to become the person we have been created to be; celebrating, developing and using that combination of gifts and experience that is uniquely ours and growing into maturity of personhood in Christ. The third vocation is to particular, recognised and authorised ministries in the Church or the world; this includes, of course, the vocation to ordained ministry. The great danger for all who have experienced the third call is that it can begin to undermine the first two. And the relentlessness of parish ministry, the fact that there is always more to do and never enough time in which to do it, can be one of the biggest contributory factors.”

At such times I peruse the Church Times jobs pages, and see things like this and wonder whether it would be the right thing to pursue. Such thoughts tend not to last for very long though. Whilst there is a sense of being in the middle of a car-crash when I think about the Church of England, I do think I am where God wants me to be. I’m not supposed to run away into the abstract. I’ve got to stick at it, partly for Bonhoefferian reasons of ‘sharing in the shame and the sacrifice’, although that is melodramatic and vainglorious. Reality is more prosaic. I think this is more to the point:

The apostolic role within established churches and denominations requires the reinterpreting of the denomination’s foundational values in the light of the demands of its mission today. The ultimate goal of these apostolic leaders is to call the denomination away from maintenance, back to mission. The apostolic denominational leader needs to be a visionary, who can outlast significant opposition from within the denominational structures and can build alliances with those who desire change. Furthermore, the strategy of the apostolic leader could involve casting vision and winning approval for a shift from maintenance to mission. In addition, the leader has to encourage signs of life within the existing structures and raise up a new generation of leaders and churches from the old. The apostolic denominational leader needs to ensure the new generation is not “frozen out” by those who resist change. Finally, such a leader must restructure the denomination’s institutions so that they serve mission purposes.

I think that’s what I’m called to do here on Mersea. Don’t expect support from the wider institutions, or approval from all sectors of the congregation(!) – just stop whingeing, and get on with the job.

Doing some research on ministry thoughts (long post coming) and discovered this little gem from July 2007:

“I was told a few days ago that there is a group of people in the parish who welcomed my arrival but who are now eager for me to be gone.”

I had forgotten that. Makes me realise that many of the tensions which erupted into the open last year had been a long time coming.

The Lord being my helper, I’m going to be here for some time yet.

Is now posted on my other blog here.

I sometimes daydream about planting a new church here on Mersea.

It would need at least a dozen people to get it going – people who were seriously committed to a path of discipleship and spiritual growth.

It would meet once a week to do the Acts 2.42 stuff, but not necessarily on a Sunday morning.

It would also meet at other times for broader fellowship, worship and teaching – understood as supplementary.

It would be a group of sojourners, tent dwellers, maybe meeting in a home or hall, maybe even meeting in an historic church sometimes.

It would pay a fair proportion (pro rata) of the parish share, but not be committed to the financial upkeep of the historic site.

It would have a cell group structure and mentality. Nurture would be done through small groups (up to half a dozen persons). It would also multiply as a whole when it grew to, say, forty people.

It would have autonomy over its manner of life; its form of worship; its expectations for social service and behaviour.

It would not have autonomy over doctrine and sacramental discipline – in other words, it would remain Anglican. It would operate under the oversight of the Rector of the parish (well I would say that wouldn’t I?) who would join in with the Acts 2.42 part, but not the rest – unless asked. It would accept the Lambeth quadrilateral as a framework for faith. However, it could sit very lightly to the Anglican acquis communautaire. It could be mostly independent of a) the inherited plant, and b) the structure of committees and processes. Although no group can operate without the formalities for long – the static latching is what enables survival over time rather than being dependent upon the passing emotions of the group.

Occasionally it would gather with the other Anglicans – and indeed the other Christians on the island – for broader worship and fellowship.

Worth exploring further?

H/T Juliet – like her I wish the presenter pronounced the name correctly, ‘Merzee’ not ‘Mercy’!

One of the issues on Mersea at the moment is the proposed installation of a new nuclear reactor at Bradwell, just across the water from us. As you can imagine, this has raised a lot of strong emotions. What I want to do in a series of posts is explore some of the different aspects to this question before, eventually, coming off the fence on the issue myself. Part of the reason for writing is, of course, to work out exactly what I think.

So why is the government looking to build new nuclear power stations? Because it has belatedly realised that there is a looming energy crisis and, if it doesn’t build new power stations, a lot of people will be trying to function without electricity in the near future.

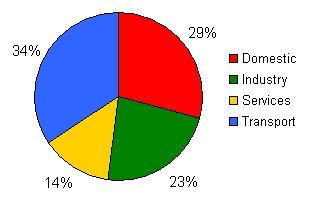

One of those nice colourful pictures that I like so much:

This shows the amount of nuclear generating capacity that is expected to go ‘off-line’ over the next decade or so. Simply to maintain a power supply equivalent to what we have today we need to find some 8GW of generation capacity. Of course, the ‘equivalent to what we have today’ understates the issue. I’ve talked about the gas situation here, but it is also worth mentioning that a number of coal-fired power stations are due to close by 2015 due to European legislation. Even if we ignore the problematic nature of depending on fossil fuels over the coming decades, we are facing a shortfall of generating capacity. Which is why the Government indicated in 2006 that they would look to build some new nuclear power stations, as part of the requirement to generate some 25GW of new capacity.

This is the first reason why the government is looking at expanding the number of nuclear power stations.

Image from here, which is highly relevant.

This was originally going to be a much longer post, but it was verging on the indiscreet, so I’ve pruned it back. The PCC might get the original version at an away day this year!

One chapter of Gladwell’s book Outliers discusses airplane crashes, specifically the way in which human communications in the cockpit directly contribute to a surprisingly high number of catastrophes. Specifically, he talks about something called the ‘Power Distance Index’ developed by Hofstede which is about the way in which less powerful members of a group accept the inequality of that power relationship. The way in which this led to plane crashes is frightening but very human: Gladwell documents cases where the assisting officers were not direct with the captain of the plane even in situations where catastrophe was imminent, eg the plane wasn’t where the captain thought it was, or where it was about to run out of fuel. Instead, the subordinate officers relied on mitigated speech, that is, they weren’t direct in telling the captain exactly what was going on, relying on hints, suggestions and euphemisms, which were catastrophically inadequate. Gladwell outlines six levels of mitigated speech, going from the most explicit to the most implicit:

1.Command – “Strategy X is going to be implemented”

2.Team Obligation Statement – “We need to try strategy X”

3.Team Suggestion – “Why don’t we try strategy X”

4.Query – “Do you think strategy X would help us in this situation?”

5.Preference – “Perhaps we should take a look at one of these Y alternatives”

6.Hint – “I wonder if we could run into any roadblocks on our current course”

What Gladwell makes clear is that communication can’t simply be analysed in terms of what is said or not said; rather it cannot be abstracted from the political context (ie hierarchy) within which communication takes place. The subordinate officers on the airplane did pass on sufficient information to the captain to make it possible for the captain to change course, if he had been actively listening. Tragically the captain – either from personality or tiredness – didn’t hear what was being said. In other words, I don’t think that the fault with the plane crashes was simply that the subordinate officers weren’t direct enough, there was an equal component where the captain was not receptive enough.

The reason why I was struck by this was because I felt it gave a lot of insight into the ‘plane crash’ that took place in the parish last year, following my decision to ask the Director of Music to retire. Without going into the messy details, I do think that the nature of communication between the various parties involved was a significant factor, not simply in terms of how explicitly various things were said or not said, but also in terms of what people were able to hear or not hear.

The Korean airline that was the principal subject for Gladwell’s analysis managed to change their culture in such a way that they were no longer vulnerable to these catastrophes. What I am pondering now is how to foster the right sort of culture within a parish whereby it is possible to genuinely ‘speak truth in love’. I think a large part of the answer has to be modelling the right sort of behaviour myself, which gives permission and space for the truth to be spoken. The two risks to avoid are ‘too much truth’ – which can become bullying – and ‘too much love’ – which means that the community simply sags into a morass of niceness.

The good news is that there is a lot of explicit Scriptural guidance on this topic, which I’m going to spend some time studying before the parish away day.

Just doing a little research on how much energy the UK uses, and where it goes – with a view to wondering what we are going to be able to hang on to. This is where we get our energy from (here)

Units are Million tonnes of oil equivalent

Coal: 37.9

Oil: 74.4

Gas: 93

Nuc: 11.9

Hydro: 1.1

Imports: 0.9

Renewables: 5.3

Total: 224.4

On an individual basis this works out at 3,814kg per head (here)

The fossil fuel elements of that are going through the peaking process, so we can expect them first to become more expensive, then to become increasingly scarce (over what I would guesstimate as a twenty year period, see my post on UK gas supply here).

Balance of payments questions

It has to be said that the UK is not best placed to withstand a constrained energy context. We import most of what we use and we are running out of ways to pay for it. This graph is from this post:

End use:

source

This is where household fuel goes:

Some rapid tentative conclusions from the household level:

this is also why combined heat and power is important

This is where the transport fuel goes (source):

Rapid tentative conclusions:

there will be much less road transport on the other side of the bump – this will be a very good thing

I don’t know much about the industrial use, so I’ll find out more about that.

Of course, all I’m doing here is thinking about an energy descent action plan. Which is what the Transition Town movement is for. Next step might be to find out more information about Mersea and how these broad patterns apply locally.

“Get a move on you ‘orrible lot! You’ve got another three miles of sand to run in, now watch your step! Move it, move it, move it!”

Not quite the exact words I heard, but close enough.

Is it wrong to occasionally wish that churches could be led like an army? More could be achieved in some ways, but doubtless that means that the mistakes would be huger alongside the successes, and I suspect a muddling through, soul by soul, is more what the Lord has in mind for us. In his patience is our salvation.

(NB Ollie was most excited to see them, thought it was great fun. I don’t plan to run along with a pack on my back any time soon though.)