This is the political reality of Europe, since nothing of importance can be done without Germany. All else is wishful thinking, clutching at straws, and evasion. If this means the euro will shed some members or blow apart – as it almost certainly does – then the rest of the world must prepare for the day.

Monthly Archives: September 2011

Quote

The fact that mark-to-market is still religiously shunned 3 years after Lehman should tell you all you need to know about what’s real and what’s not.

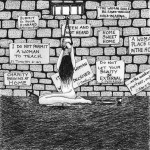

Gallery

This gallery contains 1 photo.

Women and the church (from the wonderful and inimitable Naked Pastor)

Link

Trigger’s Broom and Living Traditions

In one episode of ‘Only Fools and Horses’ Trigger is boasting about having received an award from the local council for having used the same broom for twenty years – and he then reveals that in that twenty years the broom has had 17 new heads and 14 new handles. Is it the same broom?

This is actually a new form of an ancient philosophical argument, first written down by Plutarch in the first century, where he discusses ‘The Ship of Theseus’ – a ship where all the different planks and masts and so on have been replaced over time, so that not one original piece of timber has remained. Is it still the same ship?

This is one of those questions that occupies philosophers for a very great deal of time, and I don’t plan to get very technical in this column (I have been known to learn a lesson. On rare occasions). The reason why I mention it is because it cuts right to the heart of the various changes that are going on in and around Mersea at the moment. Is it still the same Island?

My view is that Trigger’s Broom, and Theseus’ Ship, are the same, despite the changes. That is because there has been a continuity of use over time. Trigger has been using a broom to do his work in a consistent fashion for over twenty years, and each day he has taken the broom from the same place, and at the end of the day he has put it back in that place. The fact that on several occasions parts of the broom have changed has not affected the identity of the Broom – at any one point, people could have pointed to the one object and truthfully said ‘That is Trigger’s Broom’. In a similar fashion, there was a sailing vessel crewed by a community of sailors that achieved certain travels under the command of Theseus – and at any point people could have pointed to that vessel and truthfully said ‘that is Theseus’ Ship’. In other words, the identity of the object (the broom or the ship) rested as much in the continuous use by the community as in the continuity of any particular physical element.

This is a debate that often comes up when considering churches. The parish church here in West Mersea has seen vast changes in its history. The origins of the Christian community there are likely from the early seventh century, and the importance of that community (as what was then called a Minster church) was such that the King of Essex, Saint Sebbi, built the Strood in order to gain regular access to it. Almost nothing physical from that time now remains (there is one very small Anglo-Saxon carving in the church and that’s it) but I would argue that the church now is the same as the church then, simply because there has been a continuity of use on the site ever since. Similarly, the various physical changes to the church – building the tower using old Roman Tiles, the expansion of the different aisles, the massive re-ordering through the Reformation period, and more recently the installation of memorial pews and so on – all these things are simply like replacing the decking on Theseus’ ship. For some 1400 years the ‘sailors’ in the church have continued to share bread and wine while telling the story of Jesus. It is that which gives identity to the church, rather than any one particular configuration of the church fabric.

In the same way, when we are considering the various things about Mersea which may or may not be changing in the future, we need to remember that what gives Mersea its identity is not any one particular physical feature so much as the nature of the community that lives here – and that too has seen many great changes over time. The issue is perhaps not so much ‘we need to preserve that particular set of decking’ as ‘will this help us to keep sailing’? So in the context of Mersea, the questions are – what will best enable the population to flourish fully? That includes the environmental and historical questions; it also includes questions of employment and local amenities. Judging the balance between these elements is a complex task and I don’t envy those who have the responsibility for making the final decisions. I do however believe that decisions are best made at the level closest to those affected – which means, for many issues, that decisions need to be made by the Mersea community and not in Colchester.

What I am trying to describe here is the reality of a living tradition. When a tradition and a culture is alive then it is open to ongoing evolution and development in response to different circumstances – in other words the ship is kept seaworthy. It is when a tradition has begun to die that different elements from that tradition get broken off and held up as totems, the ship is only good for salvage value. At that point there is no longer a living tradition, there is a museum full of relics – and museums are wonderful and important places, they can tell us the story of where we come from and therefore help us to know where we are – but I wouldn’t want to live in one, or on one.

First world problems

Link

This is very good: “It’s cool NOT to have a Facebook account. Cool in exactly the same way that it was exciting and interesting to sign up in 2006….”

A little honesty from a market trader; listen especially to his advice at the end.

Priesthood and pastoral care

This is something I’ve been pondering anew since Graham reminded me of something Eugene Peterson wrote: “Most pastoral work actually erodes prayer. The reason is obvious: people are not comfortable with God in their lives.”

What is the specific duty of pastoral care laid upon a priest?

It seems to me that there is a general duty of pastoral care laid upon every Christian. After all, it is every Christian who is to obey the command to love their neighbour as themselves; to pray for their enemies and to practice forgiveness; to share the faith – and so on.

Clearly the priest is not to be any less obedient to those commands than other Christians – possibly they are to be more so – but is that ‘more so’ the distinctive nature of the pastoral care offered by a priest? I would say not.

If you go to a Doctor, and you find that they have what might euphemistically be called a ‘deficient bed-side manner’ you might still walk away content if you know that you have received the right medication for your ailments, and have confidence that where once you were ill, now you are on the path of becoming well.

The cure of souls should surely be the same. However good at being straightforwardly pastoral the priest may be – that is, in being generally, kind, caring, solicitous and so on – that is not the central feature of their pastoral ministry. The priest is given the cure of souls within a parish. That means that the priest is called to cultivate and exercise spiritual discernment, in order to ‘feed the sheep’ appropriately. More and more I think St Benedict’s Abbot is a good model to have in mind, as he is called to “so temper all things that the strong may have something to long after, and the weak may not draw back in alarm.”

This is not a matter of being simply kind and compassionate – although those things are in short enough supply. Rather, as with the doctor who has no social grace, it is still possible to receive cure if the person administering is competent. So the question is: in what does this competence consist?

I would suggest the following. The priest is first and foremost one in whom the conversation with God is being conducted religiously, for whom the relationship with the divine is living and active, and who is therefore able, in some small way, to bring others into that same conversation. So the priest has to be a person of prayer, and to put that life of prayer before all other duties. Secondly, the priest has to be orthodox, and have the ability to share that orthodoxy with the flock. Doctrine is pastoral; poor doctrine is at the root of a very great deal – possibly the majority – of the suffering within the churches. The role of the priest is to share a right understanding of the faith – and therefore a right understanding of how we are in the world – with those who come to them in distress. The priest is one who understands and takes seriously the nature of spiritual warfare, and who has the most effective tools with which to further that combat. Lastly, and following on from this, the priest’s ministry is necessarily sacramental as the sacramental tools are the principal means of spiritual combat. The proper use of sacramental ministry is the summation of pastoral doctrine, which achieves what it teaches. And when the priest is sufficiently advanced in the faith, then they begin to share in the nature of the sacrament themselves.

We have forgotten what priesthood is for. This is the logical consequence of losing confidence in the faith more generally. If you take the faith seriously, then you take the ability to teach the faith – and share the fruits of the faith – very seriously. If you no longer have confidence in the faith then you scratch around for more or less acceptable substitutes – priest as social worker; priest as nice person; priest as politician; priest as the entertainment package on the cruise liner. Then, slowly, the whole edifice begins to drift, and starve, and succumb to the blandishments of the world. It is because we have failed at being a Christian community that we no longer have a distinctive sense of the ministry of the priest. They are simply to be the representative ‘nice person’, and heaven help the one who fails in that most solemn of Anglican duties.

If this is truly the nature of the priesthood, how then are we to find such people? How are we to train them? The training of a priest becomes not so much a matter of choosing nice people, those with a particular gift of smal talk making them more compassionate – although one would hope and expect that to be a natural byproduct – but one of deepening an understanding of the faith, equipping them with the capacity to share that faith with those in their charge, so that the sheep are fed and ministered to. This is not an academic exercise – a filling of the mind with theory and grammar – but the conscious guiding and shaping of a person’s soul, ‘spiritual formation’. How can one hope to be a priest – and therefore seek to help form the souls of a flock – unless that process of formation has been undergone in one’s own life?

Training, therefore is not a matter of abstract academics, even less is it a matter of learning a better bedside manner. All the various elements taken over from modern management and counselling theory are at best icing on a cake, at worst they are the idolatrous substitutes that we use to try to fill the void where a living faith once was. And the church will reap what it has sown. (See John Richardson for a related thought on this from the evangelical perspective).

The situation in the Church of England regarding the training of clergy is, at the moment, very fluid, but if I were to be given some dictatorial powers I would like to see a structure which made all those approved by the Bishops’ Advisory Panels full-time employees, based in a parish, from the start, with all the housing and other benefits that a curate would normally receive. This curacy would be for a period of seven years, and during those seven years the candidate would pursue a rigorous course of theological study on a part-time (50%) basis. I would provide that theological education from a non-University setting, to avoid the Babylonian captivity of atheist academia. This would give much greater economic security to candidates – and probably to the various colleges – and would enable a much more rooted form of training.

Yet none of this would be of any benefit if the core vision of priesthood remains deficient. Until and unless we regain a sense of the nature of our faith we shall continue in our managed decline, and repeatedly sacrifice ministers and vocations to the domestic gods of the English middle class.

Gallery

This gallery contains 1 photo.

He wants to learn how to fish. I think I’m going to join him in that project…

You must be logged in to post a comment.