Should a Christian be offended by blasphemy, in the way that various Islamic groups have been offended by those cartoons? I believe not – and I’d like to explain why.

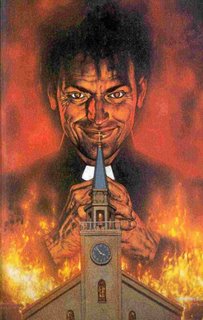

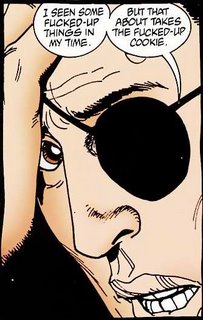

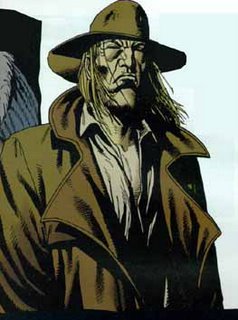

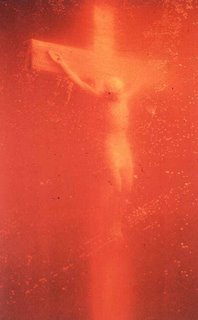

There is no shortage of material that could be cited as offensive to Christians – the ‘piss Christ’ is possibly the most egregious – but I’d like to focus on the graphic novel ‘Preacher’, written by Garth Ennis, partly because it is a cartoon/ comic, and partly because it is a work that I am familiar with.

To understand ‘Preacher’ you must imagine a tale composed of a blend of three other stories, but then put through the blender of a particular film. The three stories that ‘feed’ it are: Unforgiven, the Clint Eastwood western; the Da Vinci Code (although it predates the Da Vinci Code – it’s actually drawing on the Holy Blood and the Holy Grail); and Anne Rice’s ‘Interview with a Vampire’; and all of this is then fed through the blender of Quentin Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction”. It is certainly blasphemous, also obscene, disturbing and very funny. I believe it also makes some interesting theological points – not as profound or interesting as I had once hoped, when I was first reading it, but interesting nonetheless.

The basic plot is this: an angel and a demon come together and conceive a child; when the child is born it is immediately expelled from Heaven, and God vanishes from His throne. Genesis (the child) plummets to earth and is ‘united’ with Jesse Custer, a preacher (probably Episcopalian

Ennis grew up in Northern Ireland, not a place where balanced Christian thinking has been much in evidence, and there is clearly a kinship between the God in ‘Preacher’ and the attitudes of someone like Ian Paisley. I had hoped that there would be something theologically creative at the end – that was what kept me reading – along the lines of Genesis becoming a renewed God, essentially a retelling of the Christian story but in a modern idiom. Instead, Preacher is profoundly atheistic, and is in fact much more of a story about the importance of friendship than anything about theology. It remains deeply memorable, and the set-up I think is wonderful, but in the end there is little engagement with ‘mainstream’ Christianity – Christians within it are portrayed as either fundamentalist fascists or as idiots, and the ethics that are vindicated are those of the western, ie righteous violence.

Now, in the face of such a sustained and offensive criticism – how should a Christian react? Should a Christian shun any contact with such writing, with a view to avoiding ‘contamination’ from its blasphemy? My reading of Christianity, influenced from what I know of the work of René Girard, (partially mediated via James Alison) is rather the opposite, and that the degree of our ‘offense taking’ is the degree to which we remain to be converted to the gospel.

A key word in Girard’s analysis is skandalon (see the analysis here). It means the taking of offence, seeing something as shocking or blasphemous. As part of his anthropology, Girard argues that scandal is contagious and reproduces itself across a society, forming a major way in which a society polices its own customs. (In MoQ terms it is the most important social level pattern of value). The practices of societies are founded in sacred violence and scapegoating – in other words, societies reinforce their identity by choosing a person or group as the ‘cause’ of all their problems (think Jews in 1930’s Germany) and the society achieves a sense of unity by combining against that person or group, expelling them violently from their midst, and then telling a religious mythology justifying their actions. This practice persists over time, for the society is never able to completely eradicate tensions within itself, due to the maintenance of rivalrous desire, when one person wants what another person has.

Girard describes this contagion of scandal as the way of the world, and sees the Satan, the ‘lord of this world’ as that force which seeks to reproduce scandal, the taking of offence – for it is in the shared nature of the offence taking that the social solidarity is affirmed and reinforced. A society has a vested interest in ensuring the maintenance of scandal, for that is how the society itself is maintained. What such a society cannot accept is the continued existence of the source of scandal.

I believe this can be seen rather clearly in the case of the cartoons published by Jyllands-Posten. When they were first published, nobody in particular took offence – they were even reproduced by an Egyptian newspaper! Yet certain authorities have a vested interest in shoring up the unity of Islamic societies over against the West – the West being scapegoated as the source of the problems (internal tensions) experienced in Muslim countries. Thus it is Islamic sources which seek to generate a sense of scandal about the cartoons – to great success.

Christianity, however, begins with the scandal of the cross. That is, in the story of Jesus we have the unmasking of this process – a scapegoat who isn’t simply a victim, but one who is cognisant of this process and who forgives those who take part in it. In other words, a victim who does not take offence. This “non-taking of offence” is central to Jesus’ entire ministry – indeed, he is regularly criticised for eating with sinners and tax collectors, and memorably criticises the religious authorities saying that the prostitutes will get to heaven before them! Through not taking offence, through not seeing religious pieties as things to be defended, Jesus changes the social dynamics and enables a non-violent reconciliation with the excluded to take place. That is the essence of the Kingdom – an unmasking of this process of scandal, scapegoating and violence, in order that a new common life, not built upon these elements, can come into being.

Thus, for a Christian, it is wrong to take offence. To take offence is to play the devil’s games, to enter into antagonism between the ‘righteous’ and the ‘unrighteous’, the ‘sinner’ and the ‘saved’. In letting go of any sense of offence, one is released from the mythological pressures embedded in all stories of ‘them and us’, and is set free to become the sort of person that God originally intended – living in peace and loving the neighbour. This is what lies behind the striking language in Matthew’s gospel (5:29, where Jesus commands us to pluck out our eyes if it “causes us to sin” – language taken up by a great many moralists seeking violent self-harm, as it is, of course, to scapegoat a part of oneself). The original language used in Greek, however, is related to this word skandalon and the passage means ‘if your eye is scandalized, pluck it out’ – in other words, do not see offence.

This I find profoundly helpful, in terms of guiding my engagement and interest in the world. We are not to seek to preserve some sort of moral purity – that runs counter to Jesus’ own well documented practice. Nor are we to protest at being offended. If God does not take offence at the murder of his Son, how can we take offence at anything milder?

The lesson I take from Girard and ‘Preacher’ is that the Christian community must understand why it is seen in such negative terms, in order to move more completely into the Kingdom itself. Paradoxically, it is precisely because of this bias against ‘offence’ embedded in Christianity from the beginning that Western society has grown up with this remarkable notion of free speech and free enquiry, which is what is now at stake in the confrontation with the Islamists. It is the unmasking of the sociological processes of scapegoating and sacred violence by Jesus on the cross that fundamentally enables the fruits of Western society that we presently enjoy – including, not least of all, modern science. Girard puts it well: “The invention of science is not the reason that there are no longer witch-hunts, but the fact that there are no longer witch-hunts is the reason that science has been invented. The scientific spirit … is a by-product of the profound action of the Gospel text.”

Western civilisation is under threat and it is worth defending, but not by being offended by those who hate it, whether the Islamists, or delinquents like Andres Serrano: