First published: 19/12/07

Archbishop Rowan – peace be upon him – says in his Advent letter “a full relationship of communion will mean… The common acknowledgment that we stand under the authority of Scripture as ‘the rule and ultimate standard of faith’, in the words of the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral; as the gift shaped by the Holy Spirit which decisively interprets God to the community of believers and the community of believers to itself and opens our hearts to the living and eternal Word that is Christ. Our obedience to the call of Christ the Word Incarnate is drawn out first and foremost by our listening to the Bible and conforming our lives to what God both offers and requires of us through the words and narratives of the Bible. We recognise each other in one fellowship when we see one another ‘standing under’ the word of Scripture. Because of this recognition, we are able to consult and reflect together on the interpretation of Scripture and to learn in that process. Understanding the Bible is not a private process or something to be undertaken in isolation by one part of the family. Radical change in the way we read cannot be determined by one group or tradition alone.”

Sadly I’m coming to see that I don’t agree with this. This post explains why – and it ties in with a conversation about fundamentalism that John, Doug and some others have been having. This is really a post about my view of Scripture, and it’ll overlap with some of my recent Learning Church talks.

I think the first and most important thing to say, and the root of my disagreement with Rowan’s letter, is that I don’t see Scripture as my highest authority; I don’t see Scripture as “the rule and ultimate standard of faith”; and I don’t see Scripture as that which “decisively interprets God to the community” (my italics). To be honest, I’m surprised to hear that from Rowan, but there is a fair bit of evidence that his views have developed over the last several years.

Now why am I saying this? Am I turning into a liberal backslider? I really don’t think so. It’s more that I start from a different place – and a place that I described when discussing the Chicago Statement of Faith. I see Jesus Christ as the Word of God; the Word Incarnate; the Word made Flesh. And I understand ‘word’ to be a mere shadow of what is meant by the untranslatably rich word λογοσ – so all of the emphases relating to all things being created through him and nothing being made without him are very real and meaningful to me. Now I see that Word – the living Christ – as the highest authority, the Lord to which we are subject, and I have difficulty with something other than that Lord being put in his place! Which seems to be what Rowan’s language is doing.

Strangely enough I consider myself to have a high view of Scripture. I would want to talk about the authority of Scripture, and I would want to flesh that out with some description of what it means to live under the authority of Scripture. So, for example, I would want to say that Scripture is a) the principal witness to the Incarnation – and thereby an irreplaceable source for how we know Jesus (and that not being restricted to the Gospels, or even the New Testament); b) independent of my own preferences; and c) something which has the capacity to question and interrogate me, and overthrow my self-delusions. Yet what is often missed is that Scripture testifies about itself that it refers beyond itself. The point of Scripture isn’t that we get to know Scripture, it’s that we get to know Jesus, that we get to know the God who is revealed in Jesus. When this part of the process gets missed then we are stuck with the Pharisees who spend time searching the Scriptures and don’t realise what they are for.

What this means is that Scripture neither captures nor controls Jesus. It is of supreme importance, but it doesn’t have a lock on the living Christ. I believe that there are two other ways in which Christ can be known. I don’t believe that these ways conflict with Scripture – that is, they needn’t conflict with the proverbial ‘right interpretation’ of Scripture – but when Scripture is absolutised in this way then these other forms are needlessly, and recklessly, diminished.

The first way is through the community of the church, most particularly the sacramentally shaped community. Jesus said that wherever two or three were gathered in his name, there would he be in the midst of them. He also said that those who loved Him and obeyed Him would abide in Him, and the Father would make his home with them. This seems to me to describe an independent access to Jesus and the Father, one which is not mediated by Scripture. The community comes first; the praxis of the community drives the formation of the language which shapes and structures the community; and then Scripture captures that language and records it for posterity. Yet the life is not reduced thereby – it remains independent. I believe that Jesus can be known – and his life can be shared, in fact it IS shared – by a community gathered in His name which is concerned to love Him and obey Him. That community will undoubtedly revere Scripture, yet it need not give to Scripture the role which Rowan describes. Jesus will be found in such a community – he will be known in the breaking of the bread – and that knowing is not circumscribed by Scripture, however much the knowing in one way is interpenetrated by the knowing otherwise.

There is also, I believe, a third way in which Jesus is known – and that is by direct revelation. This need not be Road-to-Damascus style dramatics, it may be simply a long, slow dawning realisation that ‘here is Christ’, or ‘this is what Christ requires of me’. Jesus told us that at Pentecost the Spirit would come to give us all that is from Him, and that the Spirit would lead us into all truth. In other words the disciples around him did not have all truth. I don’t believe we yet have ‘all truth’, though I am sure we are more deeply embedded in it. Neither Scripture nor the community can capture the Spirit, for it blows wherever it will – but it will accomplish all that Jesus promised it would.

So I believe that there are three ways in which one can relate to the living Christ at this present time – and I do not believe that Scripture can be so construed as to become hegemonic over the other two.

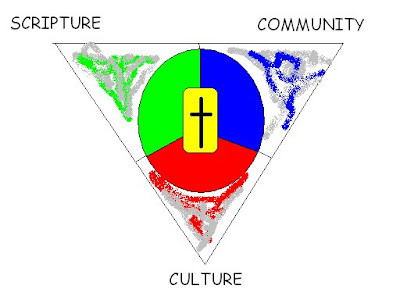

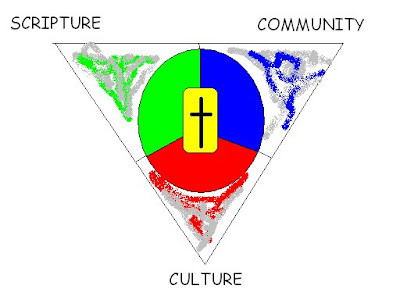

Let us return to my triangle, which I have amended:

The origin for this triangle was Hooker’s three legged stool, which I’ve always understood as the ‘classic’ Anglican approach, but I’ve made two explicit changes to it as I don’t take Hooker to have the last word(!). I have changed the word ‘tradition’ to the word ‘community’ to better reflect the nature of that field. I could have used the word ‘church’ instead, for that is what I am thinking of but I think that the word ‘community’ is less ambiguous and question-begging. (I also think that Scripture is itself a tradition!) Secondly, I have changed the word ‘reason’ to the word ‘culture’. I was never happy with ‘reason’ as the third element as reason is simply a tool not a source of authority, and as time has gone on it hasn’t captured what that third strand is really about (neither does “experience” which seems to be to be irretrievably compromised by Enlightenment metaphysics, but that’s a whole other story). What seems to be at stake in the third strand is what it means for the community informed by Scripture to incarnate in a particular time and place – not simply what is it to be faithful to Christ, and bear his witness in Scripture and Community, but what is it to be faithful to Christ here and now, in this place and this time, with these people holding these beliefs?

So I see these three sources of authority – in other words, these three ways in which the living Christ can be known – as both interdependent and themselves subject to Jesus himself, who is represented by the yellow area at the centre. I was asked, when discussing this in my lectures, about mysticism, and where it fitted in. Mysticism is the yellow area – it is where our path of discipleship is tending – it is where Christ lives in us and we live in him – and each part of the triangle is capable of leading us there.

No area of the triangle can preclude access to Christ from anywhere else and – possibly more importantly – each of the areas need the others if they are to have a full understanding of Him. The outer ‘spikes’ represent what happens when one of the areas believes it can travel alone. So the outer green represents fundamentalism; the outer blue represents a dead tradition and ritualism; the outer red represents the logical culmination of liberalism in atheism and cultural collapse.

The mid-points also represent something.

Firstly, opposite the red cultural area is a mid-point between tradition and community. This I see as ‘conservative’ Christianity, opposed to innovation, concerned to safeguard the faith that we have inherited; as opposed to the opposite side which might be seen as the ‘liberal’ emphasis in the faith – that which is most concerned to be understood in the culture as it actually exists.

Secondly, opposite the blue community area is a mid-point between scripture and culture. I see this as charismatic Christianity, concerned to express the living reality of worship and being filled with the Spirit; as opposed to the blue Anglo-Catholic area (where I would situate myself) which is most concerned to carry forward the gifts, blessings and commands which Christ gave to his body, the church.

Finally, opposite the green area is a mid-point between culture and community. I see this as liberal Catholicism – Affirming Catholicism territory – which seeks to renovate the inherited traditions of the church in such a way that babies are not discarded with bathwater; as opposed to the green Scriptural area which is concerned to be faithful to the teaching of Scripture, the Word of God written down for our instruction, God-breathed and useful. This tensional line, between the liberal Catholic and the Scriptural is clearly the one presently dividing our Communion, however differently it is described elsewhere (in other words, it’s not simply a conservative-liberal argument).

We need all the different elements in order to be complete.

Which is why I have real problems with Rowan’s letter, and the language he uses – however well supported and affirmed they might be within Scripture and the tradition of Anglicanism. What Rowan seems to have done is exclude any way in which Christ might make himself known in a new way. For undoubtedly Christ does do so, and sometimes we are called and commanded to change both how we interpret Scripture and how the community functions; that is, even when Scripture and tradition are unanimous on a matter, that is still not sufficient to capture Christ. That happened with regard to slavery; it is in the process of happening with regard to women’s ministry. The argument at present is whether it should happen with regard to homosexuality. What Rowan seems to have done, through using the language that he has, is made such a development impossible, given the form of authority that he here recognises.

My qualm is not that the changes that TEC have made are necessarily right (though I become more persuaded that they are, however many tactical qualms I have) – it is more that the schema that Rowan here endorses precludes the possibility of change as such. I can’t believe that Rowan intended this wider consequence, but nor can I see a way for the Spirit – understood as potentially conflicting with “Scripture” and “Tradition” – to be allowed to lead us into all truth.

One final aspect to all this. I feel as if I am at one and the same time finally becoming a Protestant, in the sense of abandoning catholic ecclesiology, at the same time as realising that Protestantism is an historical phase which is coming to an end. In that latter sense it is not a matter of ecclesiology but of culture, of relationships to texts and the written word, which was dominant in North-Western Europe for (say) five hundred years from the invention of the printing press to the invention of the cathode ray tube. I don’t believe that a Christian living in the contemporary world can ever have the same attitude to Scripture – indeed, to any text – as would have felt so natural as to be unobservable in the Modern era.

So I am a little troubled by the way my thoughts have gone. Yet I simply can’t see Scripture in the way that Rowan seems to require, and I suspect that I am not alone in this. So I shall continue to worry and fret about the choices that will soon be imposed upon us, yet my mind is also gaining clarity as to what is at stake, and therefore what is right. Above all, I shall continue to trust in Him who is my highest authority, revealed to me in Scripture and through my sacramental community, and who wishes for me to reveal Him here, and now, on Mersea.