A post explaining to someone who doesn’t know anything about Peak Oil why it is important, and what I think will happen. Just my opinion, of course, and I don’t really go into the religious aspects of things – it’s mainly an economic analysis. Click ‘full post’ for text.

The industrial world runs on oil – in a literal sense, in terms of the transportation system, which has been built around the ready availability of cheap liquid fuel – but also in a more fundamental sense, in that so many of our industrial products are derived or dependent upon petroleum as a raw material, in clothing, chemicals, food production and so on. This is why the maintenance of this particular energy supply is of strategic importance to all nations, not least the United States. At the end of the 1970’s President Carter committed the United States to guaranteeing the flow of energy from the Middle East, with consequences that we are all familiar with. There are no known alternatives to oil, in terms of its density, ease of use, and quantity available.

The issue about Peak Oil is that for any particular oil field, there is a point of maximum flow (the ‘peak’) after which, no matter what happens in terms of the technological expertise and financial muscle deployed, the output of oil from that particular field will decline. This was first described by a geologist working for Shell named M King Hubbert, and he described this process using a graph which has become known as the ‘Hubbert Curve’, and looks like this:

Just as one particular oil field will have an initial rise in production before peaking, and then declining, so too will areas of oil fields. For example, the British section of the North Sea has been declining in output since 1999, at an extremely rapid rate.

This is likely to have significant consequences for the UK economy, particularly the balance of payments, as we move from being an energy exporter to an energy importer.

The real issue of present concern is found when considering the world as a whole. When previous areas have ‘peaked’ in terms of the flow of oil – for example, when the United States peaked in 1970 – then other producers came along who were able to ‘take up the slack’ and this allowed the process of industrial development to continue more or less unhindered. The most important producer at the moment is Saudi Arabia, who took from the United States the role of ‘swing producer’ – that is, they were able to modulate their production of oil in order to preserve overall economic stability. When there was a shock to the system, for example after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, then the Saudi government was able to increase their own production to compensate. However, there are now strong indications that the Saudi oil fields are hitting their own ‘peak’ – and that, as one analyst has put it, ‘When Saudi peaks, the world peaks’. In other words, we are now very close to – if not just past – the moment of peak flow of oil for the world.

To get an understanding of the implications of this epochal event we can consider the problems that the United States will face over the next few years. The largest oil field in the Western Hemisphere is called Cantarell, and is found in the shallow water off the Eastern coast of Mexico. Its peak rate of production was well over 2 million barrels per day (MBD) – this in the context of a current worldwide production of oil (and oil equivalents) of around 85mbd (this graph gives the context).

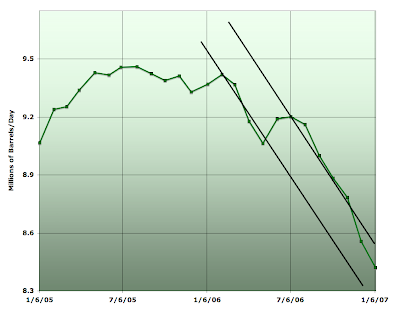

Cantarell is now in very steep decline, of the order of 20% in the last year. Graph:

The consequences of this are profound. Firstly, the oil company in charge of Cantarell is a nationalised utility (state-owned) and the revenues from the oil are responsible for some 40% of the Mexican government’s budget. There will be political consequences proportionate to the decline in revenues. Secondly, Mexico is a significant source of the oil imported to the United States – third largest after Canada and Saudi Arabia. As oil production from Mexico’s fields declines the Mexican government will face the dilemma of whether to continue to sell the oil that they are producing northwards, in order to maintain revenue, or whether to allow their own citizens to access that oil for their own purposes.

The United States economy is highly dependent upon the easy availability of petroleum – to the extent that the US consumes around 25% of all the oil produced in the world. The United States is also a very rich economy, and has, at present, very cheap petrol. Undoubtedly, to begin with, the US will pay whatever is needed to ensure the continuity of its oil supplies. The question is: from where will that oil come?

The standard answer offered by the authorities is ‘Saudi Arabia’. The Saudis assert that they have vast quantities of oil waiting to be tapped and brought into production. However, over the last year or so, their own production has been declining, despite the incentive of high prices and their own rhetoric. It is possible that Saudi production has itself peaked; we will know to a very high degree of certainty by the end of this year – if Saudi Arabia has not increased its production this year then it has almost certainly peaked. Graph:

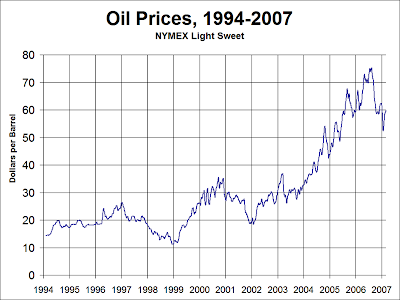

The issues raised above have been implicit within the economic system for some time; that is, the constraints of supply have caused ‘demand destruction’ as people have been priced out of the system over the last five years, as the oil price has hugely increased. Graph:

This is the first problematic: as demand continues to outstrip supply and the price rises, an economic recession will ensue. In previous periods where this has applied (1974, 1979, 1990) the supply of oil has in the end been adequate to meet the renewed demand, following the recession. The point about peak oil, as a geological phenomenon, is that without a thorough-going restructuring of our economic assumptions OIL WILL NEVER AGAIN BE ABLE TO MEET DEMAND.

There are some related issues to consider, which will add into this fundamental problem and make the overall problem swifter and more challenging to deal with.

The first is the assumption that the present worldwide market in oil will be maintained. China, whose government has been aware of the phenomenon of peak oil for some time, and has absorbed the implications of it, has been making bilateral agreements with oil suppliers around the world (eg Venezuela, several African countries) which effectively takes this oil off the market. However much the West may offer for this oil, it will not be available.

Second, as the economic environment produced by peak oil changes, it will become apparent to oil producing states that it is in their direct economic interest to keep the oil in the ground. Both Russia and Kuwait have been discussing this openly, and undoubtedly other producing countries have been discussing it behind closed doors. Given the precarious state of the US finances, it makes no sense to exchange an incredibly valuable raw material for US dollars which will sooner or later become worthless.

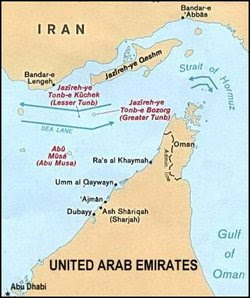

The final wild card is political; that is, the developing and widening crisis in the countries of the Middle East, especially with regard to the Iranian government’s pursuit of nuclear weaponry. Some 40% of the world’s oil is transported through the Straits of Hormuz at the outlet of the Persian gulf.

The US military believes that Iran has the capacity to shut off tanker traffic through the Straits, albeit – in their opinion – for only a short period of time. It would be best if we did not have to find out if that confidence is misplaced.

To sum up the foregoing:

– Peak Oil is a geological phenomenon that has been observed throughout the world;

– it appears that the flow of oil from all the oil fields in the world is now at its peak;

– this will have major economic consequences;

– these consequences are likely to be exacerbated by the interplay with political factors.

What I expect to happen is twofold:

firstly, oil will become more and more expensive, leading to more and more economic actors being taken ‘out of the game’. This will mean an ongoing and deepening recession that will continue until our economies have been reconstructed on a ‘steady state’ basis (ie an abandonment of the ideology of economic growth). The potentially positive aspect of this is that once the crisis has been generally realised there will be a huge amount of effort devoted to developing alternative sources of energy. I am optimistic that much of the ‘domestic’ demand can be sustained; I am convinced that the commercial demand, particularly that for individual commuting and transport, will fail, permanently;

secondly, following the period of high prices, there will develop a situation of permanent scarcity, wherein human society will either have adapted to a form of life less dependent upon easy energy, or else there will be no recognisable human society at all. To my mind the issue is the speed at which the transition from that first stage to the second takes place, and therefore how much of our present civilisation can be preserved. With enlightened political leadership and widespread popular understanding and support this crisis could be an immensely positive gift for humanity. However, it is precisely my contemplation of the absence of such leadership that persuades me that we are facing a generation of struggle and crisis, and much of humanity will not make it to the other side.

The last word can go to the Hirsch report, which was commissioned by the US government to explore the nature of the crisis which Peak Oil would provoke:

“The world has never faced a problem like this. Without massive mitigation more than a decade before the fact, the problem will be pervasive and long-lasting. Previous energy transitions (wood to coal and coal to oil) were gradual and evolutionary; oil peaking will be abrupt and discontinuous.”