First, a quotation from Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance:

“In a motorcycle… precision isn’t maintained for any romantic or perfectionist reasons. It’s simply that the enormous forces of heat and explosive pressure inside this engine can only be controlled through the kind of precision these instruments give. When each explosion takes place it drives a connecting rod onto the crankshaft with a surface pressure of many tons per square inch. If the fit of the rod to the crankshaft is precise the explosion force will be transferred smoothly and the metal will be able to stand it. But if the fit is loose by a distance of only a few thousandths of an inch the force will be delivered suddenly, like a hammer blow, and the rod, bearing and crankshaft surface will soon be pounded flat, creating a noise which at first sounds like loose tappets. That’s the reason I’m checking it now. If it is a loose rod and I try to make it to the mountains without an overhaul, it will soon get louder and louder until the rod tears itself free, slams into the spinning crankshaft and destroys the engine. Sometimes broken rods will pile right down through the crankcase and dump all the oil onto the road. All you can do then is start walking.”

I was pondering the growing food crisis and this image came to mind as an example of catastrophic positive feedback – of a system which starts to go wrong in a small way, but which is so finely calibrated that this small error impacts the system exponentially, and the whole process lurches more and more wildly before collapsing – and all we can do is start walking.

You could say that the problems that people are beginning to see with regard to food are the equivalent of the sounds in the motorcycle engine. Which then means that the most important capacity is the ability to discern and read the signals correctly. Are there loose tappets, or is the engine rod loose? At which point, an explanation of my TBTM comment that our government is institutionally incompetent.

Our government – most governments – rely upon energy resource forecasts produced by the Energy Information Agency, and a report on their recent annual conference can be found at the Oil Drum here.

As discussed in the comments, there is a profound disconnect between the two groups of people considering the available data. On one side are those whose worldview is primarily constructed from financial and economic experience and data, dominant in the EIA, which sees the availability of oil increasing out to 2030. On the other side are those who are driven more by the fields of geology and physics, who see the peak in production happening within five years at best, if not already here.

One side is hearing loose tappets. The other is hearing a loose rod.

The concern I have – originally mentioned here – is with the knock-on effects as they start to cascade through the system; the equivalent of the loose rod forcing its way through the engine and rendering it useless.

Consider some more graphs. This one is historic, and shows the decline in exports from the principal suppliers.

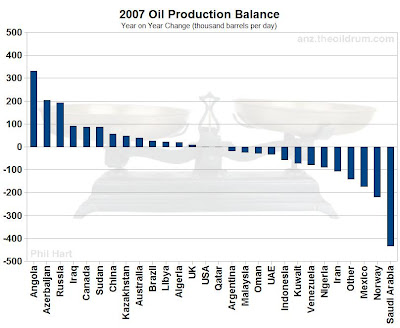

This one shows the change in production over the last year (which reinforces the point about exports).

Essentially, the “Peakists” envision a period twenty or so years from now when there is practically no fossil fuel available in the West – in other words, availability at around 10-20% of its present availability. (Note: availability, not cost). Whereas the EIA envision a smooth increase in oil supply in response to demand.

It’s impossible to predict how the impacts of peak oil will feed through the system, but that there will be catastrophic failure if the Peakists are correct is unarguable. The issue is whether what we are experiencing already is a loose rod or a loose tappet.

I have just planted an apple tree in our back garden. We’ll be planting some more in the coming weeks.