Category Archives: philosophy

Lego God

A comment I’ve left over on Stephen Law’s site, which may be worth sharing here.

My kids like to play with lego (so do I). Imagine they are making an item – eg a spaceship – and there is a piece missing, and the ship doesn’t function properly without it.

The ‘god of the gaps’ argument says that God is the missing piece. Which leads to all sorts of problems for theology when the missing piece is discovered down the back of the sofa.

I would argue that God is Lego as such. That is, all the pieces are part of God. God is not so much a missing piece so much as the precondition for being able to build things at all.

In other words, the individual lego pieces are different aspects of life that are meaningful.

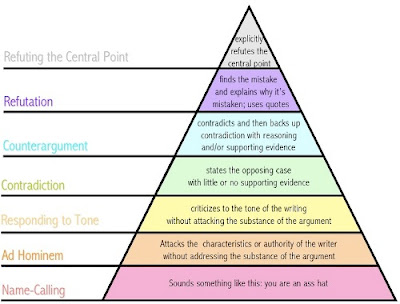

How to argue

There’s a lot I could say about this but for now I’m just going to sigh with relief.

(Stolen from OSO)

Meaning, Suffering and Integrity

Returning to the discussion about suffering. This is long (c 3700 words).

We had an interesting reading from Romans in our last Sunday service:

“…but we also rejoice in our sufferings, because we know that suffering produces perseverance; perseverance, character; and character, hope. And hope does not disappoint us, because God has poured out his love into our hearts by the Holy Spirit, whom he has given us.” (Rom 5.3-5, NIV)

~~~

What does it mean to believe in God? Specifically, what does it mean for a Christian to believe in God? As I understand it, the essential element is about meaning or purpose – to believe in God is to believe that life is meaningful, is purposeful, and this meaning is by definition independent of personal choice or preference, it is something that stands outside of our desires and it is something to which we need to conform in order to flourish. The Christian claim is that this meaning became manifest in human form in the person of Jesus of Nazareth who taught, was crucified and rose again on the third day two thousand years ago. This is what is meant in the prologue to John’s gospel: the Word became flesh. The logos (meaning, purpose) took human form, lived amongst us, full of grace and truth. Thus, there may be many ways of describing meaning in human life; the Christian claim is that this meaning is explicitly revealed in Jesus yet (if a Christian accepts that all things were made through Christ) we can expect to find meaning outside of the Christian tradition. No genuine human meaning is incompatible with Christianity.

~~~

Consider what happens at a church wedding, and specifically the contrast with a state service. At both of them legal vows will be exchanged, yet in the former the language and liturgy of God is foremost; in the latter all references to religion are forbidden. Specifically, in the vows spoken in a church service there is the phrase ‘in the presence of God I make this vow’.

What is being referred to with this language of God is precisely the larger purpose, the larger framework of meaning, within which the vows have their place. There is an acknowledgment of several things: that the desires of the couple are not sovereign; that they are dependent upon God’s grace for the health of their relationship; that the commitment is sacred involving the most profound elements of the personality; that the process is open-ended, may involve drastic change to one or both parties, but that the covenant being made in the sight of God is being set up above whatever individual choices and preferences the parties bring to the agreement.

In other words, a marriage is not just a contract. To say that the marriage is being made ‘in the presence of God’ is to place the relationship in that larger framework of meaning and purpose from which all other meanings and purposes (in a Christian culture) derive their sense. It is about rooting the relationship in a much longer and deeper pattern of life than personal choice and desire.

It is, of course, perfectly possible to have a non-Christian wedding service that partakes of this same character, eg Jewish, Hindu, Buddhist wedding services. What I do not perceive to be possible is to have an explicitly atheist wedding service which partakes of the same sharing in a wider purpose, independent of human choices. The difference I perceive between humourless and sophisticated atheism is that the former doesn’t recognise there to be any problem here; the latter does, and offers alternatives. It is not so much the word ‘God’ itself that matters, it is the acknowledgment of something higher.

~~~

How does human suffering fit in with this context of meaning? How does this understanding of the word ‘God’ fit in with “the problem of suffering”? There seem two ways to address this issue, one academic, one more personal.

The academic issue is to point out inconsistencies between supposed attributes of God and the presence of suffering, either as a logical problem (see here) or as an ‘evidentiary’ problem (see here). The greatest problem of these academic approaches is that they mistake the nature of (in particular) Christian faith in God. There are three inter-linked problems:

i) it is a central claim of the tradition that God is ultimately mysterious and not finally knowable. We cannot attain to a position of oversight with respect to God, we are always in an inferior position – that’s part of what the word ‘God’ means – something which is above and beyond our comprehension. Any analysis which seeks to render God’s attributes definable is not engaging with a Christian analysis;

ii) related to this is the axiom that I have mentioned several times before about idolatry. This can be defined in several ways, one of the simplest being ‘God is not a member of a set’ (including the set of things which are not members of a set!). This is a rule of thumb – a grammatical rule – determining how the word God can be used. What it means is that nothing definable in the human realm can be given an absolute meaning. All things are subject to change;

iii) a third implication is that it is blasphemous to try and justify God to humanity – what is technically called theodicy – because the attempt necessarily violates points i) and ii) above, and therefore runs counter to the meaning and purpose that the word God refers to. This doesn’t mean that the problem can’t be considered and clarified further through discussion – it does mean (and this is something that is slowly dawning on me personally) that the faithful not only cannot provide an intellectually satisfactory answer, but that they mustn’t. This is one of the points I take from the Hart article.

~~~

One of the problems that I have experienced in discussing this issue is that many theologians explicitly pursue theodicies. The implication of my argument above is that they are faithless. I do not believe it to be an accident that Modern Protestants are over-represented amongst such thinkers.

A Modern Protestant might agree that ‘There is an x such that x is God’. More traditional Christians cry out with Augustine ‘our hearts are restless until they find their rest in thee’.

~~~

You can add up the parts

but you won’t have the sum

You can strike up the march,

there is no drum

Every heart, every heart

to love will come

but like a refugee.

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

(Leonard Cohen, Anthem)

~~~

The more personal problem of suffering relates to what people actually do when they are faced with suffering. When a person’s world crumbles around them because of a particular turn of events is it still possible to claim that life is still meaningful? Does the language about the world having meaning and purpose, apart from our own choices, still make any sort of sense when confronted with life-shattering circumstances? The question could be: when we are in the pit of despair, is there a ladder that can be used to climb up out?

There are at least three options:

i) a nihilist answer: there is no ladder. Life is bleak and meaningless. There is no higher purpose. Get used to it! Stop indulging in lily-livered sentimentalism and self-deceit. The trouble I see with this sort of answer is that it destroys everything that makes humanity distinctively human – there is no longer any human Quality available. There is nothing to build a life around.

ii) an enlightened existentialist answer: make the ladder yourself, out of your own resources. Where I think this line of thought breaks down in this context (it breaks down elsewhere too) is that it is appealing to resources of character and moral strength that may be precisely what have been exhausted by the suffering.

iii) a Christian (or other religious response) which, ultimately, ends up talking about mystery. That which was thought to be God – a stable source of meaning and value – turns out now to be no such thing. Either there is no God (options i) and ii) open up) or else God is not what God was thought to be. In other words the context of suffering is one where we are brought closer to reality and closer to God. For they are the same thing in the end. Option iii) is essentially a declaration of faith.

~~~

This was a sermon I gave at the funeral of a teenage girl who had taken her own life:

We have come and gathered in this church today to mourn the death of _____; to lament for a life lost all too soon; to seek some measure of understanding of what has been, and perhaps, some hope for what will be.

In all of the tragedies offered up in our human life, very few are as severe or as painful as the loss sustained by ________’s family. It is a loss which shatters all the foundations on which a family is built up – the bonds of love and trust which hold a family together. As the reading from the book of Lamentations puts it – “In all the world has there been such sorrow?” And this shock and grief is not confined to ________’s own family, for it is something which affects the entire community, all of us gathered here today. For we do share life with each other. We are not separate from each other. We are our brother’s keeper, and our sister’s keeper. And so this wound, which is so overwhelming for _______’s family, is also a wound in our community, our fellowship of neighbours and friends. Where do we go from here?

When someone takes their own life, we who are left behind are confronted with questions. The pain inside demands an answer, and so the mind tortures itself with doubt and worries. Was there something that I could have said differently that might have prevented this? Was there something I could have done that would have eased the pain in _______’s heart? If only I hadn’t done this or said that. This is our natural reaction, it is a reaction of care and concern which demonstrates the love we had for _______. But ultimately, there can be no final answers; there certainly cannot be any final blame. We are confronted, in _______’s taking of her own life, with a deep and a very painful mystery. And all we can ask is ‘why?’ Perhaps most of all, we ask, ‘Why God? Where were you in all this?’ For it seems to me that when we are faced with pain that we do not understand, when we come close to being overwhelmed by it, what is most painful is the meaning of what has happened. We ask the question why. Why God? Why?

In our gospel reading we heard the story of the death of Lazarus, which also gathered a community together in grief. When Jesus comes to Mary and Martha he is too late to prevent Lazarus’ death – Lazarus, whom he loved and befriended. And it wasn’t that Jesus couldn’t get there in time – he chose to delay for a few days. And both Mary and Martha ask him why, saying “Lord, if you had been here, Lazarus wouldn’t have died.” We don’t know why Jesus didn’t come immediately. Just as we don’t know why nothing prevented _______’s death. We do know that Jesus was terribly upset by the death, and by the grief of the community. And in consequence, Jesus acts to raise Lazarus from death, to unbind him from his shroud and release him from his tomb. Lazarus is set free from death – a promise of resurrection that is extended to all who trust in Jesus.

But why couldn’t Jesus just have prevented the death in the first place? Why couldn’t God make a world which doesn’t have suffering in it? Why can’t he tell us how and why it all makes sense – why is it that this world is the sort of place that _______ couldn’t cope with, when she had so much to live for, and there was so much love available for her? I have no easy answer for that question. We live within the world that He has created, where we must wrestle and struggle with this mystery of human pain and suffering. But in the face of that suffering, I do believe that there is the possibility of hope; and that hope is the only answer we can find, which might heal our wounds.

For Christians follow an innocent man who was hung to death on a cross; and a representation of that event hangs above me now. And his cry from the cross was “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” For Jesus also felt abandoned by God, even he couldn’t understand what it was that was happening. And yet on the morning of the third day, he was raised to life again, which is why we still talk about him over 2000 years later. This might seem just to replace one mystery with another, but what has changed is that we can hope. For when we are confronted with pain that we don’t understand, when we feel cheated by life, we still have a choice. We can say that life is meaningless, that it doesn’t make sense, and reject everything that God has given to us. But if we do that, we never move away from the cross. We remain rooted in our pain and we never get to Easter morning. For the alternative is to say, although I don’t, although I can’t understand how this tragedy can make sense, I trust… I trust that God is in charge, that He loves us, and that no one who is truly loved is ever lost. For love is eternal, it is what the world is made of, and it is what the maker of this world is made of.

In the face of the pain of this tragic event, if we can trust in God, if we can hold on to hope, we can trust that one day we will share in that resurrection when, finally, we will understand how and why it all makes sense. On that day we shall be reunited with those we love, and then there will be no more pain, there will be no more grief and sorrow, and God will gently wipe away every tear from our eyes.

~~~

I see the personal problem as much the most important and significant question to address. That is why I want to know what (humourless) atheists would say to people in concrete situations. Do they choose option i) or ii) or do they choose different ones? It’s not a trivial request and the discussion will forever share a certain abstract and unreal quality until answers are provided.

“Life can educate one to a belief in God. And experiences too are what bring this about; but I don’t mean visions and other forms of sense experience which show us the ‘existence of this being’, but, eg, sufferings of various sorts. They neither show us God in the way a sense impression shows us an object, nor do they give rise to conjectures about him. Experiences, thoughts, – life can force this concept on us.” (Wittgenstein, 1950)

Why is it that it was the highly educated in Paris who were so shocked by the Lisbon earthquake, whereas those who had experienced the suffering carried on with their prayers? Could it be that for all their intellectual refinement they were not as in touch with reality as the poor Portuguese? It is, after all, part of the logic of belief in God that non-belief is evidence of delusion, of a failure to properly grasp the nature of reality.

~~~

Can the ladder be climbed up? Or is it simply delusional to think that life is meaningful?

One of the things that I feel is often missed in discussion with atheists is the necessary connection between ‘God’ and ‘meaning/purpose’. From my perspective you cannot have one without the other – which means that if meaning and purpose are accepted as part and parcel of human life then that necessarily implies a belief in God.

Of course, the word ‘God’ is not the crucial thing here. The attainment of union with that meaning and purpose could be called Nirvana and still be referring to the same thing. The language that has been developed in our culture happens to be drawn from the Jewish and Christian scriptures. The way in which we talk about things that are worthwhile, indeed, what sort of things we count as being worthwhile, are inherited from this Christian context.

What is important is not the words or rituals that are used but the life that is lived. And where the life is lived with hope, integrity and purpose – there is God.

“What can we bring to the Lord?

What kind of offerings should we give him?

Should we bow before God

with offerings of yearling calves?

Should we offer him thousands of rams

and ten thousand rivers of olive oil?

Should we sacrifice our firstborn children

to pay for our sins?

No, O people, the Lord has told you what is good,

and this is what he requires of you:

to do what is right, to love mercy,

and to walk humbly with your God.” (Micah 6.6-8 NLT)

~~~

I was profoundly struck by Scott g’s comment (here)”pirsig painted constant attempts to have us resonate with a model of ‘quality,’ both by what it is and what it isn’t, and i would expect you to constantly attempt to paint whatever you need to to have us resonate with ‘god.’ this is the difference between what you do, and what pirsig does. what pirsig does is enlightening, and what you do is frustrating. pirsig wants us to get it. you seem to not want us to get it.”

I think I have been at fault in these discussions. The first fault is one which the interlocutors at Stephen’s site have picked up on, describing me as having a strategy “of obfuscation and smokescreen delivered with an air of intellectual and spiritual superiority.” I am culpable of intellectual arrogance. Specifically: I do believe that no open-minded person with a genuine curiosity about the issues could remain a humourless atheist; I do see it as an intellectual backwater driven more by a polemical agenda than a heartfelt pursuit of truth. Which is why I enjoy engaging with sophisticated atheists so much – they recognise, inter alia, that a) there is more to Christianity than Modern Protestantism; b) that the rhetoric of science doesn’t match up with the reality; c) that the heritage of Christianity is still dominant in Western societies; d) that Christianity and other religions engage in certain humanly essential pursuits which need to be addressed by anything purporting to replace it.

I think I need to repent of some intellectual arrogance, and that repentance needs principally to take the form of listening more attentively to interlocutors. What went wrong with the recent conversation at Stephen Law’s site would seem to be that I lost track of what was actually being asked.

There is a second fault flowing from this, and from the above. I have been engaging in the argument on secular terms and it is becoming more and more clear to me that the framework of the debate is inherently atheistic. That is, it is impossible to explain the word ‘God’ and all that it means whilst accepting a secular frame of reference (and by secular I mean the late Modern Protestant framework that most Philosophy of Religion is pursued within).

Scott correctly identifies the solution: ‘pirsig painted constant attempts to have us resonate with a model of ‘quality,’ both by what it is and what it isn’t, and i would expect you to constantly attempt to paint whatever you need to to have us resonate with ‘god.’

I think this is exactly right. I need to talk positively about what God means – God as understood and explored within the mainstream Christian tradition. God is not a concept to be defined but a reality to be explored. And I have no desire to hide that in a smokescreen.

~~~

What I am really thinking about is a discussion of ‘the way’. Protestant cultures have a high reverence for words – it is a legacy of the technological revolution which put the Bible into every household, as the immediate source of authority. Yet words are ultimately useless. Another Wittgenstein reference: ‘it has been impossible for me to say one word in my writings about all that music has meant to me in my life. How then can I hope to be understood?’

I do need to talk about the way – about how meaning and purpose are integrated into a life – about how the presence of suffering not only doesn’t destroy that meaning but is tied up with it, in that the most profound understandings of meaning and purpose come on the far side of the suffering, not before.

And the way is not something reducible to words. It has to be shown in order to make any sense. Which brings us back to where I began – with Jesus. Christianity makes no sense without him, without what he taught, how he lived, how he died and rose again. The way I would want to describe is the way that he walked. It is not a matter of words but of the Word – the logos. The logic which animates Christian life, and which can’t ultimately be wrapped up in neat and tidy definitions. It can only be shown with a life.

~~~

An honest religious thinker is like a tightrope walker. He almost looks as though he were walking on nothing but air. His support is the slenderest imaginable. And yet it really is possible to walk on it.

Wittgenstein, 1948

Reasonable Atheism (22): The problem of definitions

In the debate going on at Stephen Law’s place (here) The Celtic Chimp made this comment:

“I eventually had to give up arguing with Sam. His beliefs are so vague and insubstantial that I have come to doubt that Sam himself knows what he believes. I think ‘God cannot be the member of any set’ was the straw that broke the camels back.

I offer fair and honest warning to anyone with a healthy respect for actually taking a definable position. Debating with Sam is like going to the movies to see a film. There are tons of adverts for forthcoming movies and then the credits roll.”

I thought this was quite an amusing image, but it needs a decent response – click ‘full post’ for text.

In a debate where one person refuses to give a concrete definition of their terms, it is understandable that the other parties become frustrated because this seems to go against all the norms of proper philosophical debate. However, what this reveals is the desire for ‘definitions’ – and this desire is one of the main targets of Wittgenstein’s philosophical therapy.

Some paragraphs edited from this essay.

For Wittgenstein the source of the traditional approach to philosophy was Socrates (he sometimes called the source of confusion ‘Plato’s method’).. He once said to his friend Drury [Quoted in The Danger of Words, M O’C Drury, Thoemmes Press, 1996, p115.], ‘It has puzzled me why Socrates is regarded as a great philosopher. Because when Socrates asks for the meaning of a word and people give him examples of how that word is used, he isn’t satisfied but wants a unique definition. Now if someone shows me how a word is used and its different meanings, that is just the sort of answer I want.’ Or consider these remarks, the first made in 1931, the second in 1945: ‘Reading the Socratic dialogues one has the feeling: what a frightful waste of time! What’s the point of these arguments that prove nothing and clarify nothing?’; ‘Socrates keeps reducing the Sophist to silence, – but does he have right on his side when he does this? Well it is true that the Sophist does not know what he thinks he knows; but that is no triumph for Socrates. It can’t be a case of “You see! you don’t know it!” – nor yet, triumphantly, of “So none of us knows anything”.’

I expect that Wittgenstein had in mind a passage such as this one, from Socrates’ first speech in the Phaedrus: ‘in every discussion there is only one way of beginning if one is to come to a sound conclusion, and that is to know what one is discussing… Let us then begin by agreeing upon a definition’. In the conclusion of the Phaedrus Socrates restates this: ‘a man must know the truth about any subject that he deals with; he must be able to define it.’

For Wittgenstein it is this emphasis upon definability in words which is the source of all our metaphysical illusions. For Wittgenstein Socrates was the source of all our metaphysical troubles, and the source of (for example) Descartes’ ‘clear and distinct ideas’ lies ‘…as deep in us as the forms of our language’. It seems clear that, as Baker and Hacker put it in their commentary on the Investigations [GP Baker and PMS Hacker, Wittgenstein: Meaning and Understanding, Blackwell, 1997, p350], ‘Wittgenstein noted that some of the deep distortions of meaning, explanation and understanding originate with Plato’.

Consider this remark of Wittgenstein’s from 1931: ‘People say again and again that philosophy doesn’t really progress, that we are still occupied with the same philosophical problems as were the Greeks. But the people who say that don’t understand why it has to be so. It is because our language has remained the same and keeps seducing us into asking the same questions. As long as there continues to be a verb ‘to be’ that looks as if it functions in the same way as ‘to eat’ and ‘to drink’, as long as we still have the adjectives ‘identical’ ‘true’ ‘false’ ‘possible’, as long as we continue to talk of a river of time, of an expanse of space etc etc, people will keep stumbling over the same puzzling difficulties and find themselves staring at something which no explanation seems capable of clearing up. And what’s more, this satisfies a longing for the transcendent, because in so far as people think they can see the “limits of human understanding’ they believe of course that they can see beyond these’.

Fergus Kerr has written that ‘The history of theology might even be written in terms of periodic struggles with the metaphysical inheritance’ [Fergus Kerr, Theology After Wittgenstein, Blackwell, 1986, p187.] and it does seem as if there is something intrinsic to metaphysical endeavour which is inimical to the practice of theology, certainly on a post-Wittgensteinian account of metaphysics. The argument ultimately concerns the nature of language and how far it can express religious truth. For Wittgenstein ‘the words you utter or what you think as you utter them are not what matters, so much as the difference they make at various points in your life’ [Culture and Value, p85] and I think that this is wholly in tune with Wittgenstein’s comment that he would by no means prefer a continuation of his work to a change in the way people live which would make all these questions superfluous.’

For Wittgenstein it is always action which is primary – ‘In the beginning was the deed’ – and our language gains its sense from being embodied in certain practices. Consider the following passage (written in 1937): ‘Christianity is not a doctrine, not, I mean, a theory about what has happened and will happen to the human soul, but a description of something that actually takes place in human life. For ‘consciousness of sin’ is a real event and so are despair and salvation through faith. Those who speak of such things (Bunyan for instance) are simply describing what has happened to them, whatever gloss anyone may want to put on it.’

~~~

The reason why the Chimp finds me evasive, and others call me ‘more slippery than soap’ is because a) I don’t believe we can define God, b) I don’t think definitions are the be-all and end-all of fruitful discussion, but most of all c) because I accept that ‘practice gives the words their sense’ – and it is only by attending to the practice of Christian life, most of all in the Eucharist, that Christian understandings of God can be found.

Reasonable Atheism (21): Atheism and moral relativism

Some engagement with Tony Lloyd’s logic (which I mostly agree with).

Sam’s comments in italics.

If X follows from Y then it is not the case that you have Y and not X.

Minor quibble – I think you need the word ‘necessarily’ in there to exclude other conditions, but we can take that as read.

Moral subjectivism “M” would follow from Atheism “A” (“M follows from A”) if, and only if, you cannot have not-M and A at the same time. If we can show not-M and A then we have refuted “Moral subjectivism follows from Atheism”.

So far so good.

Logical

The import of a logical assertion of “M follows from A” is that it is inconsistent to hold “A and not-M”.

I do not see any contradiction in:

1. God does not exist

2. You should do what is right

Indeed there cannot be any contradiction. Whether God does, or does not, exist is a factual statement: an “is” statement. Whether we should do what is right is an ethical statement: an “ought” statement. The oft repeated maxim “you cannot get from ‘is’ to ‘ought’” can be rephrased as “an ‘ought’ statement does not follow from an ‘is’ statement”.

This is where it starts to get complicated, a) because no definition of God is offered, and b) because of the reliance on ‘no ought from is’. A Christian would deny b) because of their understanding of a) (and their ‘definition’ of God probably differs also). So if the premises are different it’s not surprising that different conclusions follow.

Mind you, Peter Hitchens may not agree that you cannot get from ‘is’ to ‘ought’. Let’s ignore the maxim and look in a little more detail. What does “moral subjectivism” mean? It plainly means that one considers morality to be a function of something about the subject. “It’s right, because I like it” would be a good summary of the position. So person does not subscribe to moral relativism if they hold that “it is not necessarily right just because I like it”.

Not sure I’d run with ‘It’s right because I like it’. I would rather have something like ‘I choose what is right’. Not sure this affects the underlying logic though.

“It would be wrong to kill Elton John even though I would dearly like to” would be an example of an objective moral statement, if I held to that I would be denying Moral Subjectivism.

The question at issue is whether atheism offers any intellectual support to that statement. Also, saying ‘it would be wrong to…’ could simply be a pragmatic recognition of social mores. What is the atheist meaning when they say this?

Is there any contradiction in:

1. God does not exist

2. It would be wrong to kill Elton John even though I would dearly like to

No. For it to be a contradiction would be to add a third premise:

3. If God does not exist then nothing is wrong.

I accept 3. I would also affirm the reverse – if something is wrong (outside of our choices and preferences, either individually or collectively) then God exists. That’s a central part of what I understand the word ‘God’ to mean.

There is nothing contradictory in holding that some things would be wrong if God does not exist.

This is what needs to be unpacked. This doesn’t need to be in the sense of providing a ‘basis’ or ‘foundation’ for something being wrong (although that’s perfectly possible). What I am after is something distinguishing ‘holding something to be wrong’ from ‘I choose (or like) X’.

Empirical

Even though it is possible to hold to moral objectivism and atheism at the same time without contradiction it may be in fact impossible. It may not contradict the meanings of the word but may contradict the facts about how people are. Does, in practice, Moral Subjectivism follow from Atheism?

“Blackness follows from raven-ness” (all ravens are black) can be refuted by showing a raven that is not black. If we change the hypothesis to say “Blackness generally follows from raven-ness” we can refute that by showing a lot of ravens that are not black, enough to rule out the word “generally”.

On the empirical side I give you Japan and China. The vast majority of these populations are atheist. The vast majority are not moral subjectivists, they do not think it is fine to act however one wants but that you should do what is right whether one likes it or not.

I agree with this. What I find interesting is how their “atheism” differs from that offered in the West, ie they have something to put in its place as a frame of reference for evaluating moral situations. I want to know what a Western atheist puts in place of the inherited Christianity.

“I’ve not seen it refuted anywhere”

You have now. But more importantly Peter Hitchens has heard it refuted. The above is the general import of Christopher Hitchens’ more colourful question: (paraphrasing from memory) “are you telling me that before the Ten Commandments came the Israelites wandered the wilderness thinking that murder, adultery and false witness was perfectly acceptable until God told them to “cut it out”?”.

The distinctive part about the Ten Commandments is the first half, not the second (and the first half gives specific weight to the second). I recently read that the first elements of the Ten Commandments are unique to Israel.

I repeat the original allegation. Not only does Atheism not entail Moral Relativism but Peter Hitchens knew that when he wrote the piece. He wrote it because of the rhetorical effect it would have not because he thought it true. That is defined as “bullshit”.

My concern is that the logical point (you don’t have to be a moral relativist if you’re an atheist, look at the Chinese) is being used to evade responsibility for the pragmatic social consequences (most atheists within UK society are moral relativists; the one led to the other historically; and moral relativism contributes to the breakdown of society). I’ve asked before about this – I want to know what are the generators of moral growth within an atheistic (Western, humourless) frame of reference?

ADDENDUM – picking up one thing from Tony’s later comment: “It depends on what you mean by “appeal can be made”. Do you mean that, in the last analysis it is the individual who decides what to do? In that case the statement is true, but trivially so. Even with an authority you have decide whether to obey it or not. In the last analysis the Pope is a catholic because his individual conscience tells him to be.”

I don’t think it is trivially true – partly because of an understanding of ‘obedience’ but more profoundly because of the nature of moral growth. ‘Ah, now I understand’ doesn’t seem to be possible if there is nothing outside of the individual’s choices to determine what is right and wrong. Conscience undoubtedly has a crucial place, but catholic theology recognises the importance of the conscience being educated, in other words there is an iterative engagement between conscience and authority that leads to right judgement. I want to know what stands in the place of the authority for the (western, humourless) atheist.

Theodicy meme

To my great pleasure and interest, people are running with the theodicy meme.

These are the answers I’ve found so far:

Peter

John

Doug

Iyov

Velveteen Rabbi (lovely title for a blog)

Lingamish

Jim West

James McGrath (and I should say that clicking through to his site made me see a tremendously significant SPOILER for the next episode of Lost which has made me a trifle upset; I normally postpone reading James until after I’ve seen the relevant episodes!)

Eddie Arthur

Journeyman

Tom

Chuck Grantham

Tzvee Zahavy

Duane Smith

Alto Artist

Amber Temple

Mark Woo

Several responses at Sarx

I’ll try and keep tabs on them all and put the links up here.

For my earlier post on the problem of suffering go here.

The meme is being spread around the community of believers (from which I gain reassurance that my perspective is not at all unusual) but criticisms from an atheist angle can be found at Stephen Law’s place. He’s written quite a lot about it (see here).

Reasonable Atheism (19): Four questions on theodicy

In a comment, scott (gray) asked these four questions, which I think could work as a meme…

1. if the nature of god is omnipotent, benevolent, and anthropomorphic (that god is a person, who sees suffering as wrong, and can change all of it), why does god not act to relieve all suffering, or at least the greatest amount of suffering for the greatest amount of people the greatest amount of time?

2. if you were god, and you were omnipotent and benevolent, how would you respond to suffering?

3. if this is not the nature of god, what is the nature of god, that allows suffering in the world?

4. if these are the wrong questions to ask, what are the right ones?

My answers:

1. Put briefly I don’t think that these philosophical categories map naturally onto the Christian God (they are Greek rather than Hebrew?). In particular God does not act arbitrarily (that is, he is consistent) and therefore once he is in the relationship of creator to creation, which allows freedom, he doesn’t overpower that freedom of creation. Hence we have sin which causes suffering (which is a way of saying: Christians interpret suffering as estrangement from God. I think there is a deeply embedded overlap here between the orthodox Christian view and the Buddhist idea that suffering is illusion, but I would want to ponder that more).

2. Well, I’m not God and part of the problem is that God’s will is by definition unfathomable. I’m not sure that a God who was fully explicable in human terms would be worth worshipping. I think this is one of the most crucial areas that lead to incomprehension on the part of atheists, because belief in God requires a certain degree of surrendering judgement and that is so profoundly taboo in Modern understandings that it is barely even mentionable.

3. The nature of God is resurrection after crucifixion. Suffering is overcome and redeemed, not blotted out.

4. I think the question I would want to pursue in the context of a conversation about suffering is: what makes life meaningful in the face of death? Does anything matter? How do we order our lives in such a way that they gain integrity and depth and meaning in the face of what can appear a totally capricious fate? (Nussbaum is really good on outlining the Ancient Greek interpretations of this in The Fragility of Goodness) It seems to me that as soon as a positive answer to these questions is explored either all meaning is self-generated and chosen (which is the specifically Modern conceit) or else we begin to talk about meaning being derived from something apart from our choices. At that point we have entered the realm of religious language and theology.

To turn it into a meme, I tag John, Peter, Paul, Joe and Tom.

Reasonable Atheism (18): Hart, Law and the problem of suffering

I sent a link to David Bentley Hart’s article on the problem of suffering to Stephen Law, which has occasioned some discussion, much of which seems to be incomprehension. I think this is a good example of where there is some talking past each other going on (partly because Hart’s argument is addressed to a Christian audience) so I thought I’d try and summarise what Hart’s argument is. Click ‘full post’ for text.

As I read it, Hart is arguing for the following four points (my emphases in bold):

1. The problems thrown up by these catastrophes are not new problems

“…nothing that occurred that day or in the days that followed told us anything about the nature of finite existence of which we were not already entirely aware.”

2. Atheists don’t understand Christian perspective

“…it is difficult not to be annoyed when a zealous skeptic, eager to be the first to deliver God His long overdue coup de grâce, begins confidently to speak as if believers have never until this moment considered the problem of evil or confronted despair or suffering or death.”

“It would have at least been courteous, one would think, if he had made more than a perfunctory effort to ascertain what religious persons actually do believe before presuming to instruct them on what they cannot believe.”

(On Voltaire’s response to the Lisbon earthquake): “Voltaire’s poem is not a challenge to Christian faith; it inveighs against a variant of the “deist” God, one who has simply ordered the world exactly as it now is, and who balances out all its eventualities in a precise equilibrium between felicity and morality.”

3. It is the fault of Christians themselves that they’re not understood – lots of bad theology

“In truth, though, confronted by such enormous suffering, Christians have less to fear from the piercing dialectic of the village atheist than they do from the earnestness of certain believers … more troubling are the attempts of some Christians to rationalize this catastrophe in ways that, however inadvertently, make that argument all at once seem profound.”

“All three wished to justify the ways of God to man, to affirm God’s benevolence, to see meaning in the seemingly monstrous randomness of nature’s violence, and to find solace in God’s guiding hand. None seemed to worry that others might think him to be making a fine case for a rejection of God, or of faith in divine goodness. Simply said, there is no more liberating knowledge given us by the gospel — and none in which we should find more comfort — than the knowledge that suffering and death, considered in themselves, have no ultimate meaning at all.”

Dostoevsky: “Ivan asks, if you could bring about a universal and final beatitude for all beings by torturing one small child to death, would you think the price acceptable?”

“Voltaire sees only the terrible truth that the actual history of suffering and death is not morally intelligible. Dostoevsky sees — and this bespeaks both his moral genius and his Christian view of reality — that it would be far more terrible if it were.”

“No less metaphysically incoherent — though immeasurably more vile — is the suggestion that God requires suffering and death to reveal certain of his attributes (capricious cruelty, perhaps? morbid indifference? a twisted sense of humor?). It is precisely sin, suffering, and death that blind us to God’s true nature.”

“…consider the price at which that comfort is purchased: it requires us to believe in and love a God whose good ends will be realized not only in spite of — but entirely by way of — every cruelty, every fortuitous misery, every catastrophe, every betrayal, every sin the world has ever known; it requires us to believe in the eternal spiritual necessity of a child dying an agonizing death from diphtheria, of a young mother ravaged by cancer, of tens of thousands of Asians swallowed in an instant by the sea, of millions murdered in death camps and gulags and forced famines. It seems a strange thing to find peace in a universe rendered morally intelligible at the cost of a God rendered morally loathsome.”

4. Suffering is evil, a cosmic disorder, which will be put right (ie mended)

“Ours is, after all, a religion of salvation; our faith is in a God who has come to rescue His creation from the absurdity of sin and the emptiness of death, and so we are permitted to hate these things with a perfect hatred. [SN: ie not try to justify them] For while Christ takes the suffering of his creatures up into his own, it is not because he or they had need of suffering, but because he would not abandon his creatures to the grave.”

“As for comfort, when we seek it, I can imagine none greater than the happy knowledge that when I see the death of a child I do not see the face of God, but the face of His enemy. It is not a faith that would necessarily satisfy Ivan Karamazov, but neither is it one that his arguments can defeat: for it has set us free from optimism, and taught us hope instead.”

“We can rejoice that we are saved not through the immanent mechanisms of history and nature, but by grace; that God will not unite all of history’s many strands in one great synthesis, but will judge much of history false and damnable; that He will not simply reveal the sublime logic of fallen nature, but will strike off the fetters in which creation languishes; and that, rather than showing us how the tears of a small girl suffering in the dark were necessary for the building of the Kingdom, He will instead raise her up and wipe away all tears from her eyes — and there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying, nor any more pain, for the former things will have passed away, and He that sits upon the throne will say, “Behold, I make all things new.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~

In sum, Hart is arguing that Christian theology does not seek to explain or justify the existence of suffering in the world in terms of God’s ultimate purpose. Suffering is understood as a disorder, a privation of the good, something which is opposed to God and which can therefore be ‘hated with a perfect hatred’.

Lying behind this article is another perspective that needs to be taken account of in order to understand his argument, about what it means to call God ‘good’. Orthodox Christianity is very careful about what it means to call God ‘good’ because of the ever-present danger of tacitly assuming a place from which to judge God as either good or evil. So when a Christian believer calls God ‘good’ the language does not function in the same way as it would when such a Christian describes another person as good (or evil), and, further, it becomes just as meaningful to describe God as the source of suffering (of ‘weal and woe’ as Isaiah puts it) as it would be to describe God as source of good things when those good things are judged as such in human terms.

This is why possibly the most important sentence in Hart’s article is this comparatively early one: “Simply said, there is no more liberating knowledge given us by the gospel — and none in which we should find more comfort — than the knowledge that suffering and death, considered in themselves, have no ultimate meaning at all.” In other words, the problem of suffering is not as important as we might think it to be, and when Christian theologians treat this problem as something that calls into question the existence of God, they are giving it more importance than it deserves (as a theological question). If this world is all that there is, then the problem of suffering is enhanced – for in the face of suffering and death, how can meaning be established? Yet if – as Christian theology insists – there is more to life than what we can perceive with our immediate material senses, then it is possible to assert that meaning (and therefore the language of faith – Godtalk – theology) persists in the face of suffering.

One way of bringing this out is to return to the question of Voltaire and the response to the earthquake in Lisbon. There was no immediate cessation of belief in God on the part of the residents of Lisbon, rather the opposite. It was only on the cultured sensibilities of Voltaire and his ilk that this event had such an impact; as Hart implies, it was only to theodicy – which, as a form of justifying God to humanity, cannot be orthodox Christianity – that such events were a shock. I do not believe it to be accidental that it is to the increasingly affluent and cultured despisers of faith that such traumas are experienced as shocking. Those who spend their lives more closely engaged with the daily reality and struggle for existence, who are much more acquainted with suffering on a daily basis, are also the ones in whom religious faith is most deeply rooted. (But then, they tend not to be educated in the Western sense, so their views don’t count…)

The possibility and relevance of unmediated experience

An essay I wrote for my MA at Heythrop, relevant to a debate going on at the moment.

1. This essay will be concerned with the possibility and relevance of unmediated experience, that is, an experience which is not determinatively shaped by the prior conceptual background of the subject. The essay therefore seeks to understand the debate provoked by Steven Katz in his original article ‘Language, Epistemology and Mysticism’[1], and taken forward in particular by Robert Forman in his edited work ‘The Problem of Pure Consciousness’[2]. Forman’s work was provoked by the work of Steven Katz, and much of the development of his ideas comes in dialogue with Katz. In this essay, therefore, I shall first outline the argument as Katz presents it, provide a summary of Forman’s response, and indicate my own position. I shall then consider what is at stake in the debate as a whole, drawing on some criticisms made by Grace Jantzen.

‘There are NO pure (i.e. unmediated) experiences’

2. Katz’s article is concerned to argue the following case:

> there is no such thing as a pure experience;

> therefore all mystical experience is constituted by a formative tradition; and therefore

> the proper form of study of mystical experience is through respecting difference.

Katz begins his article[3] by taking issue with the attempt to account for the phenomena of mystical experience by assuming that there can be any experience apart from the cultural grounding in which such experience is found. Katz claims quite baldly that there can be no such thing as a pure experience. He writes:

‘…let me state the single epistemological assumption that has exercised my thinking and which has forced me to undertake the present investigation: There are NO pure (i.e. unmediated) experiences. Neither mystical experience nor more ordinary forms of experience give any indication, or any ground for believing, that they are unmediated. That is to say, all experience is processed through, organized by, and makes itself available to us in extremely complex epistemological ways. The notion of unmediated experience seems, if not self-contradictory, at best empty.’[4]

For Katz both the experience itself as well as the report made of it are ‘shaped by concepts which the mystic brings to, and which shape, his experience…the forms of consciousness which the mystic brings to experience set structured and limiting parameters on what the experience will be’[5]. Once Katz has explained this guiding assumption, the remainder of his article is concerned with drawing out the implications for the study of mysticism.

3. Katz develops his argument by first considering recent work by Zaehner and Stace. He criticises Stace for being arbitrary in choosing which experiences are to be counted as prior, and for seeing the full force of the point that experience is mediated. Zaehner is criticised on three counts: he is concerned only with post-experiential testimony; his account is distorted by the need for Catholic apologetic; and his phenomenology, although not without merit, is ultimately too simplistic – ‘Zaehner’s well known investigations flounder because his methodological, hermeneutical, and especially epistemological resources are weak.’[6]

4. This is followed by discussions of different forms of mysticism: Jewish, Buddhist and then Christian, the weight of which is concerned to establish the way in which tradition and formation shapes what is experienced. In the course of this discussion, Katz also criticises reliance upon a sense of the ‘ineffable’ to establish commonality between mysticisms. He points out that, purely as a logical matter, if ‘the mystic does not mean what he says and his words have no literal meaning whatsoever then not only is it impossible to establish my pluralistic view, but it is also logically impossible to establish any view whatsoever. If none of the mystics’ utterances carry any literal meaning then they cannot serve as the data for any position…’ (This is supported later in the paper when he points out that merely to say that mystics share an experience of an ineffable and paradoxical nature is not to say that those experiences are of the same ineffability or paradox: ‘To assume, as James, Huxley, Stace and many others do, that, because both mystics claim that their experiences are paradoxical, they are describing like experiences is a non sequitur.’) Katz reaches the interim conclusion that ‘mystical experience is ‘over-determined’ by its socio-religious milieu: as a result of his process of intellectual acculturation in its broadest sense, the mystic brings to his experience a world of concepts, images, symbols, and values which shape as well as colour the experience he eventually and actually has.’[7]

5. In the final section of his paper, Katz broadens his concern to look at questions of language in the study of mysticism. He is concerned to argue that much study of mysticism is misled by superficial resemblances in the surface grammar of mystical speech, without proper regard to what the meaning of such speech might be in its original context. He writes ‘What emerges clearly from this argument is the awareness that choosing descriptions of mystic experience out of their total context does not provide grounds for their comparability but rather severs all grounds of their intelligibility for it empties the chosen phrases, terms, and descriptions of definite meaning.’[8] For Katz, such considerations ‘lead us back again to the foundations of the basic claim being advanced in this paper, namely that mystical experience is contextual’[9] because ‘This much is certain: the mystical experience must be mediated by the kind of beings we are.’[10]

The Possibility of Unmediated Experience

6. This paper is concerned primarily with the possibility of ‘unmediated experience’, which Katz openly describes as an ‘assumption’ in his article, and so it will not closely examine other elements of his paper. Suffice to say that the assertion that the traditional background of a mystic will play some part in preparing for or influencing what is experienced, and that it will determine the way in which such experiences are described – in other words, the second element in his argument – is comparatively uncontroversial; and consequently the third element of his argument, although not without problems relating to the emphasis on difference[11], is also comparatively uncontroversial. However, before beginning to focus on his guiding assumption, it would be worth pointing out that Katz’s avowed pluralism leads to significant problems with his overall project, on three separate grounds:

a) The claim to neutrality between different religious claims is self-refuting, as it takes up a position antagonistic to the claims of the religions themselves;

b) Similarly, with respect to his relativistic perspective, which pretends to a neutral stance from which to observe phenomena without acknowledging the commitments of that stance itself; and

c) His claim that religious perspectives are incommensurable is problematic as that would disallow any form of comparative religious study (for what is to count as a religion?) and therefore rule out the possibilities of articles such as his own.

Put broadly, Katz is situated within a distinctly modernist (post-Kantian) sensibility, which seeks to articulate an objective perspective over diverse phenomena, and which is silent on its own (significant) commitments, as it seeks to arbitrate between different concerns. Such a standpoint is illegitimate if it claims to provide the ‘final truth’ about the nature of mysticism.

7. Forman takes issue with Katz on a number of grounds. He begins his criticisms[12] by stating that Katz ‘maintains two interconnected theses which are linked by an unstated presupposition’. Those theses are, first, Katz’s assertion that all experiences are mediated by our conceptual understanding, and, second, that different religions provide different ‘sets’, i.e. different beliefs and concepts. According to Forman, the logical product of these theses is pluralism, which Forman takes to be important for Katz and others as it represents the rejection of the ‘perennial philosophy’ which maintains that there is a common experience in mysticisms across different traditions.[13] The first of these theses Forman characterises as constructivism, and for Forman this is the source of the difficulties in Katz’s outlook (Forman considers the second thesis, concerning different ‘sets’ to be something which ‘no right thinking person would disagree with’[14]). According to Forman, Katz describes ‘a process in which we impose our blanks or formularies onto the manifold of experience and encounter things in the terms those formularies define for us’[15], which can fairly be characterised as a constructivist position. Forman argues that Katz needs to be committed to a ‘complete’ constructivist thesis for his argument to hold. A modified constructivism might allow for some experiences to be only partly formed by the prior conceptual map, yet that would immediately allow for the claim that it is the non-conceptually formed part of an experience which is essentially mystical, and Katz’s argument breaks down: ‘the best way (perhaps the only way) to protect the pluralist hypothesis is through a complete constructivism’.[16]

8. Moving to specific criticisms of Katz’s article, Forman argues that Katz’s position has the virtues of credibility and respect for the differences between different traditions, but that these virtues are vitiated by fundamental problems with the overall perspective. Forman makes the following points:

a) Katz commits the fallacy of petitio principii, by which he assumes what he is trying to prove. Katz does assert that his paper ‘will attempt to provide the full supporting evidence and argumentation that this process of differentiation of mystical experience into the patterns and symbols of established religious communities is experiential and does not only take place in the post-experiential process of reporting and interpreting the experience itself: it is at work before, during, and after the experience.’[17] Yet as Forman correctly points out, ‘All [Katz] offers are summaries of religious doctrines and restatements of the original assumption. These are instances of an assumed claim, not arguments.’[18]

b) The argument as developed by Katz and colleagues is systematically incomplete. That is, there is no indication as to what concepts and beliefs are to count as important for the shaping of experience. Yet if no limits are applied, the argument is evacuated of meaningful content, for at that point it would have to be argued that all concepts shape all experiences, and ‘all of my experiences would change with every new notion learned. This is clearly absurd, for…I can only learn within a coherent set of experiences which are part of a single consistent background for any experience’.[19] This impales Katz upon a dilemma, for either no limits are applied, which renders the argument empty, or else limits are applied, and this opens up scope for asserting the existence of parallel experiences shaped by a common heritage (e.g. from neo-Platonism in Jewish, Sufi and Christian mysticism), which undermines the pluralism thesis.

c) Katz is careless of the distinction between sense and reference, i.e. that similar language can refer to different things, or, conversely, divergent language can refer to the same thing. Conceptually, as Forman points out, it makes sense to imagine cases where different religious traditions might consider the experiences of a concrete individual, and say ‘that is experience X’ or ‘that is experience Y’. Forman writes ‘There is no problem in using different terms with different senses to refer to the same experience. Whether this is, in fact, what they would say is not a matter for a philosopher to decide in advance’.[20]

d) Forman’s final specific point claims that Katz commits the fallacy of post hoc, ergo propter hoc. Logically, it is perfectly possible that the relationship between belief and experience is contingent rather than necessary, and Forman refers to the different gastro-intestinal experiences undergone by an Eskimo and a Frenchman – the differences in culture and expectation will no doubt shape the experiences undergone, but that does not mean that the culture caused the experiences themselves (the food did that).

Interim conclusions

9. What can be made of Katz’s assertion that ‘There are NO pure (ie umediated) experiences’, for this does represent the foundation of his argument? The first thing to note is that there is no epistemological discussion concerning what is to count as ‘experience’ – whether pure or not – and this is part of Katz’s general inadequacy on questions of epistemology.[21] If experience is taken to mean ‘whatever may happen to an individual’ then it would seem uncontentious to suggest that humans might experience something which is unmediated by prior concepts or beliefs – an obvious example is of a small child experiencing pain, but that can extend to, eg, the instinctive recoil from a hot stove which happens without any nerve signal passing through to the brain. Yet this is not of great significance for our discussions, as the discussion of mysticism depends upon the reports made by mystics of what they have experienced (or, more accurately, upon the teaching of the mystics). The question therefore stands as to what is to count as an experience. An interim definition might be ‘an event undergone by an aware subject, which impinges upon their understanding’. The argument that there is no such thing as a pure experience is therefore that there are no events, which have consequent implications in terms of understanding etc., that are not themselves the products of a prior understanding, and related to this is the argument that it is meaningless to talk of ‘non-conceptual’ experience (because ‘non-conceptual’ is itself a conceptual term). A useful interlocutor to introduce at this point would be Thomas Kuhn, for his understanding of the way that scientific understandings change can provide a non-religious parallel for our discussions. It seems to me that there is a parallel between the constructivist position articulated by Katz and what Kuhn describes as ‘normal’ science, and between the experiences that Forman is concerned with and what Kuhn describes as ‘creative’ or ‘revolutionary’ science.

10. Over the last thirty five years or so there has been a great deal of historical investigation of the way in which scientific revolutions or paradigm shifts take place, sparked in the main by Thomas Kuhn’s ground-breaking study The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. [22] Contrary to the received (modernist) opinion that science provided a sure path to knowledge, and that science developed in slow methodical steps to a greater understanding of the truth, Kuhn showed that there were a large number of non-rational factors at work in any paradigm shift. For Kuhn, the great majority of scientific enquiry normally takes place within a particular paradigm. For example, to establish the particular way in which one species has evolved requires research, and the way that that research is constructed is governed by the assumptions inherent within the dominant paradigm. It is rather as if the paradigm has set down railway tracks down which the practice of scientific enquiry must travel. In this way the normal practice of science, in fact the vast majority of what is currently described as science, is a deductive and non-innovative activity. The practice of scientific method is applied to a particular area, in line with the assumptions of the dominant paradigm, and the conclusions derived from experiment or observation are then added in to the relevant body of knowledge. Most science is essentially puzzle solving. As such, this form of scientific endeavour is determinatively shaped by the conceptual background of the researcher, and is open to the type of constructivist interpretation favoured by Katz.

11. However, in contrast to this is revolutionary science, which is when a dominant paradigm is overturned in favour of a different understanding. Classic examples of revolutionary science are the change from a Ptolemaic to a Copernican cosmology, Darwin’s theory of evolution, and the change from a Newtonian paradigm to an Einsteinian paradigm. As normal science proceeded within a particular paradigm data experienced would be either incorporated into the prevailing worldview or be rejected as erroneous, but over time there would develop an increasing number of anomalies and inconsistencies between the information gathered and the dictates of the overarching paradigm. The paradigm would be revised piece by piece until the weight of anomalies became too great. At that point the most creative scientists would develop a different paradigm which, once articulated, would then be used to interpret the information gathered in a new and more productive way. As Kuhn writes[23] ‘the perception of anomaly – of a phenomenon, that is, for which his paradigm had not readied the investigator – played an essential role in preparing the way for perception of novelty’. This would seem prima facie to be a well understood example of an experience which was not conceptually determined by the background attitudes and beliefs of the observer. Indeed, by definition, such background details cannot have formed the experience, for it is the status of the attitudes and beliefs that is called into question by the experience.

12. I would argue that the constructivist position, as articulated by Katz, is ultimately a sterile one, which precludes any understanding of normal intellectual (or spiritual) development. Forman makes this point when he argues that the constructivist hypothesis has difficulties in finding a place for creative novelty in their schema[24]. As such I would argue that it IS possible to have an experience which is not mediated by a prior conceptual world-view, and that there is such a thing as unmediated experience. The anomalies described by Kuhn fall into that category by definition, because they are experiences which are not fully understood – the scientist is baffled – and it is only at a later stage, once the overall conceptual framework has changed, that the experiences are able to be linked in with the beliefs and conceptual heritage of the individual concerned. I therefore judge that Katz is wrong to disallow any possibility of unmediated experience, and that Forman is correct to argue for its possibility.

The relevance of unmediated experience

13. Forman spends much time, with his colleagues, in developing a theory of the ‘Pure consciousness event’ and exploring some of the ramifications of this theory. Whilst I have some sympathy for his account, not least in the way in which it can have a spiritually beneficial function in provoking a growth of understanding, this last section of my essay shall be concerned with a criticism of Forman’s approach. This line of criticism is not concerned so much with the possibility of a pure experience, as with its religious relevance.

14. In her book ‘Power, Gender and Christian Mysticism’[25] Grace Jantzen makes the argument that who is to count as a mystic, and what is to count as mystical writing, has changed over time, and been subject to political, especially patriarchal control. From its original sense relating to ancient Greek mystery cults, through the early Christian understanding relating to the discernment of meaning in scripture, in our present age mysticism has come to refer to a highly exalted state of feeling: ‘Instead of referring to the central, if hidden, reality of scripture or sacrament, the idea of “mysticism” has been subjectivised beyond recognition, so that it is thought of in terms of states of consciousness or feeling.’[26] This transition from the public realm to private sensation has the political consequence of marginalising the testimony of the mystics and a significant part of Jantzen’s argument is to show that this transition coincided with the growth of women’s voices in the mystical tradition – so part of the effect of this shift has been to minimise the impact of women’s voices: ‘It was only with the development of the secular state, when religious experience was no longer perceived as a source of knowledge and power, that it became safe to allow women to be mystics…The decline of gender as an issue in the definition of who should count as a mystic was in direct relation to the decline in the perception of mystical experience, and religion generally, as politically powerful’.[27]

15. My interest here is not so much with the gender issue as with the broader political issue. For it seems clear that the modern conception of mystical experience, deriving from Schleirmacher via William James[28], which emphasises the importance of personal feelings, stands in marked contrast to the testimony of the Christian mystics themselves. In particular, the idea of ineffability (that is, the via negativa, or the apophatic path) has changed from being an imagery concerned with letting go of false idols to being a direct report of personal experience. The principal reservation that I have about Forman’s account is that he is concerned with an abstraction from living religious traditions. Although he concedes that this is only one part of the spectrum of mystical experiences, and he does ‘not regard it as salvific in and of itself’[29] I would put the case more strongly: unless these experiences are able to be absorbed and valued by a religious community, then they are irrelevant to theology.

Conclusions

16. Katz’s paper was explicitly based on the assumption that ‘There are NO pure (i.e. unmediated) experiences.’ This assumption is unwarranted. For the reasons outlined by Forman, and by consideration of the parallel experiences in scientific research it would seem clear that there are experiences which are not wholly constructed by the conceptual background of the individual. To assert that there are no such experiences is to deny any possibilty of creative development, and, if nothing else, that stands in contrast to the mystical teachings which Katz is claiming to study. However, the existence of unmediated experience is, of itself, not religiously significant. Forman would appear to stand in the line of modernist interpretation which emphasises the importance of the individual experience[30]. Yet this highly academic approach does seem to have disengaged with all that is most vital and distinctive in the religious tradition itself. Two points are worth making in conclusion. The first is that the mystics worked and taught within the context of a living tradition – they were deeply engaged with the inheritance of faith. As Bernard McGinn puts it, ‘No Mystics (at least before the present century) believed in or practiced “mysticism”. They believed in and practiced Christianity (or Judaism, or Islam, or Hinduism), that is, religions that contained mystical elements as parts of a wider historical whole’.[31] Secondly, the mystical path, the attempt to discern the nature of God – and to thereby be transformed by God in turn – has what would now be considered essentially political consequences. The fruits of mystical contemplation were to be found in increased social engagement – in the search for justice and mercy in the wider social sphere, hence the concern for the relief of poverty on the part of the mendicant orders and the Beguines. As such, the existence of unmediated experience needs to be subjected to a rigorous religious critique. Fortunately, the writings of the mystics themselves provide the ideal raw material for such a study.

Bibliography

Language, Epistemology and Mysticism, Steven Katz, in Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis, Steven Katz (editor), Oxford University Press (London: Sheldon Press), 1978.

The Problem of Pure Consciousness, Robert K C Forman (editor), Oxford University Press, 1990.

Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Chicago, 2nd Edition, 1970.

Grace Jantzen, Power, Gender and Christian Mysticism, Cambridge University Press, 1995

Mark A McIntosh, Mystical Theology, Blackwell, 1998

Denys Turner, The Darkness of God, Cambridge University Press, 1995

Footnotes

[1] Language, Epistemology and Mysticism, Steven Katz, in Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis, Steven Katz (editor), Oxford University Press (London: Sheldon Press?#), 1978. Hereafter LEM.

[2] The Problem of Pure Consciousness, Robert K C Forman (editor), Oxford University Press, 1990. Hereafter: PPC.

[3] LEM p23-4.

[4] LEM p26. Emphases in the original.

[5] LEM p26-7. Emphasis in the original.

[6] LEM p32.

[7] LEM p46.

[8] LEM p46-7.

[9] LEM p56-7.

[10] LEM p59.

[11] For example, the fact the people share a common humanity (a common physiology), born of a common existence on one planet, would provide some grounds for optimism relating to the exploration of common elements between different religions.

[12] PPC p9.

[13] I should point out that Forman is not consistent in his discussion of ‘theses’ and ‘axioms’. He moves from claiming that there are “two theses” linked by a “presupposition”, to describing the second thesis AS the “unstated presupposition”, and then to describing a “third axiom of the essay”, as a product of the first two. The “two theses” that he refers to at the beginning can therefore be taken to mean either 1. No unmediated experiences AND 2. Different religions have different sets; or 1. No unmediated experiences AND 2. Pluralism. My account takes the first of these two options as determinative, as the references later in the article seem to imply that this is Forman’s own preference.

[14] PPC p10.

[15] PPC p11.

[16] PPC p14.

[17] LEM p 27.

[18] PPC p16.

[19] PPC p17.

[20] PPC p18.

[21] For a detailed discussion of this point, see the essay by Donald Rothberg, Contemporary Epistemology and the study of Mysticism, in PPC, pp163 – 210.

[22] Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Chicago, 2nd Edition, 1970.

[23] Kuhn, 1970, p57.

[24] PPC 19-21.

[25] Grace Jantzen, Power, Gender and Christian Mysticism, Cambridge University Press, 1995

[26] Jantzen, p317.

[27] Jantzen, p 326.

[28] For an overview of the history, see Jantzen pp304-321.

[29] PPC p9

[30] To be fair to Forman, his position is a little more subtle. In his discussion of Eckhart, for example, he concedes that Eckhart’s intention is that ‘the contemplative life is only complete when brought into action’ (PPC p114).

[31] Bernard McGinn, The Presence of God: A history of Western Christian Mysticism, p xvi, quoted in Denys Turner, The Darkness of God, Cambridge University Press, 1995, p261.