I resubscribed to the Economist a few months back, largely because I became interested in current affairs again as a result of understanding Peak Oil. Ironic really. In the latest edition there is an article criticising the Peak Oil theory. As there are some serious errors and omissions in the article, I thought that I would write a detailed rebuttal of it here. My comments below are in bold, the text of the Economist article (relevant extracts) is in normal type.

~~~

…Now comes what appears to be the most powerful threat to oil’s supremacy in a century: growing fears that the black gold is running dry. For years a small group of geologists has been claiming that the world has started to grow short of oil, that alternatives cannot possibly replace it and that an imminent peak in production will lead to economic disaster. …But is the world really starting to run out of oil? And would hitting a global peak of production necessarily spell economic ruin? Both questions are arguable. Despite today’s obsession with the idea of “peak oil”, what really matters to the world economy is not when conventional oil production peaks, but whether we have enough affordable and convenient fuel from any source to power our current fleet of cars, buses and aeroplanes.

So far, so good. The issue is only secondarily an energy crisis, it is primarily a liquid fuels crisis. The Hirsch report is good on explaining this.

With that in mind, the global oil industry is on the verge of a dramatic transformation from a risky exploration business into a technology-intensive manufacturing business. And the product that big oil companies will soon be manufacturing, argues Shell’s Mr Van der Veer, is “greener fossil fuels”. The race is on to manufacture such fuels for blending into petrol and diesel today, thus extending the useful life of the world’s remaining oil reserves. This shift in emphasis from discovery to manufacturing opens the door to firms outside the oil industry (such as America’s General Electric, Britain’s Virgin Fuels and South Africa’s Sasol) that are keen on alternative energy. It may even result in a breakthrough that replaces oil altogether.

I find this line of argument profoundly strange. If we are not running out of oil, why the shift? But if there is the shift, doesn’t this mean that we are running out of oil, and therefore needing to look at substitutes? This is a theme in the article that I find incoherent. There are other problems with this, but I’ll discuss them below.

To see how that might happen, consider the first question: is the world really running out of oil? Colin Campbell, an Irish geologist, has been saying since the 1990s that the peak of global oil production is imminent. Kenneth Deffeyes, a respected geologist at Princeton, thought that the peak would arrive late last year.

It did not. In fact, oil production capacity might actually grow sharply over the next few years (see chart 1).

This I find astonishing – brazen untruth from the Economist! To say baldly ‘It did not’ would imply that we have increased our production from the time of Deffeyes prophecy (one of many he has made, to be fair). Yet it is not the case that our oil production has increased – but unless you were following the situation, and knew the details, simply reading the Economist would be profoundly misleading. Stuart Staniford has been keeping track of the production data, and the current ‘record’ of actual production was in May 2005 (matched in December 2005 – Deffeyes prediction) . His most recent analysis is available here. NB There have been previous ‘plateaus’ in oil production, this may prove to be another. Note, of course, the heavy weight placed on the weasel word ‘might’ in the last sentence.

Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA), an energy consultancy, has scrutinised all of the oil projects now under way around the world. Though noting rising costs, the firm concludes that the world’s oil-production capacity could increase by as much as 15m barrels per day (bpd) between 2005 and 2010—equivalent to almost 18% of today’s output and the biggest surge in history. Since most of these projects are already budgeted and in development, there is no geological reason why this wave of supply will not become available (though politics or civil strife can always disrupt output).

The CERA figures are fairly widely accepted as accurate for the amount of new capacity coming on stream. What they ignore, however – and where the real meat of the discussion lies – is whether the depletion rate of established oil fields will overwhelm this new capacity. In other words, whether the running down of production from old oilfields will outweigh the production from the new fields. All the signs are that this is exactly what is happening.

Peak-oil advocates remain unconvinced. A sign of depletion, they argue, is that big Western oil firms are finding it increasingly difficult to replace the oil they produce, let alone build their reserves. …It is true that the big firms are struggling to replace reserves. But that does not mean the world is running out of oil, just that they do not have access to the vast deposits of cheap and easy oil that are left in Russia and members of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). And as the great fields of the North Sea and Alaska mature, non-OPEC oil production will probably peak by 2010 or 2015. That is soon—but it says nothing of what really matters, which is the global picture.

This is an optimistic analysis of non-OPEC oil. At least they have implicitly accepted the notion of ‘peaking’ – and this represents progress.

When the United States Geological Survey (USGS) studied the matter closely, it concluded that the world had around 3 trillion barrels of recoverable conventional oil in the ground. Of that, only one-third has been produced. That, argued the USGS, puts the global peak beyond 2025.

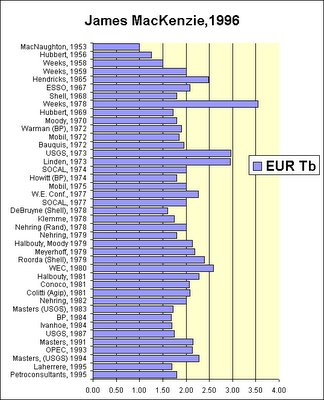

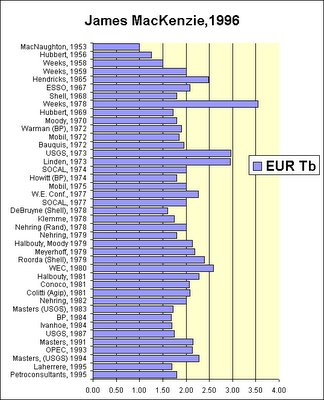

This is probably the biggest error in the article – an uncritical acceptance of the USGS figures, which have been widely discredited. The USGS figures for total reserves are hypothetical, based upon a 50% probability of discovery (in other words, it is equally likely that they are wrong) and the total figure stands in stark contrast to that arrived at from many other academic studies. Consider this chart:

Here you should be able to see how much of an oddity the USGS figure is, compared to that arrived at by many other independent geologists. The figure of 2.1 trillion barrels of oil, ultimately recoverable, is more soundly based, and undermines the point that the Economist writer is making.

It is also true that oilmen will probably discover no more “super-giant” fields like Saudi Arabia’s Ghawar (which alone produces 5m bpd). But there are even bigger resources available right under their noses. Technological breakthroughs such as multi-lateral drilling helped defy predictions of decline in Britain’s North Sea that have been made since the 1980s: the region is only now peaking.

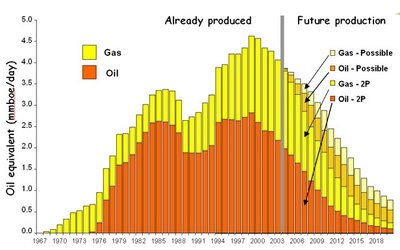

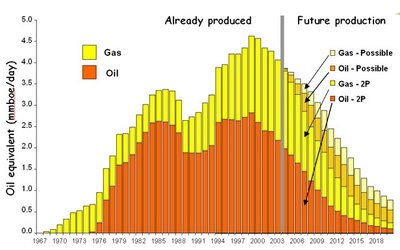

This is either a simple error or disingenuous. Britain’s North Sea fields peaked in 1999 and are declining extremely rapidly – see graph below (source for figures: DTI).

If the world fields decline as swiftly then the doomer scenario will unfold and we are looking at severe population decline. However, the change of language in the article (from ‘Britain’s North Sea’ to ‘the region’) makes me suspect that the writer is shifting to include the Norwegian sectors, etc, when ‘only now’ might (just) be defensible (ie only a year or three out). This is just sloppy journalism.

Globally, the oil industry recovers only about one-third of the oil that is known to exist in any given reservoir. New technologies like 4-D seismic analysis and electromagnetic “direct detection” of hydrocarbons are lifting that “recovery rate”, and even a rise of a few percentage points would provide more oil to the market than another discovery on the scale of those in the Caspian or North Sea.

This line of argument has been extensively discussed by Deffeyes et al. Whilst there is undoubtedly some element of technological impact, it is nowhere near enough to offset the decline in production, and in fact is more likely to increase the decline rate, from gentle slope to scary cliff – as has been demonstrated in the North Sea, where all the most modern technology in the world is doing nothing to slow the decline.

Further, just because there are no more Ghawars does not mean an end to discovery altogether. Using ever fancier technologies, the oil business is drilling in deeper waters, more difficult terrain and even in the Arctic (which, as global warming melts the polar ice cap, will perversely become the next great prize in oil). Large parts of Siberia, Iraq and Saudi Arabia have not even been explored with modern kit.

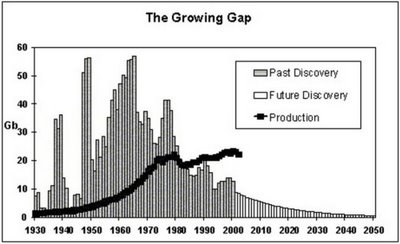

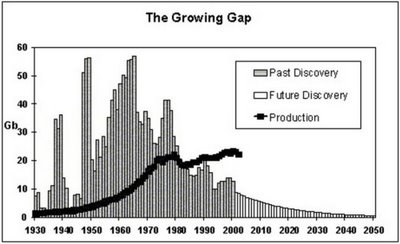

It’s possible that there will be more oil discovered – indeed, that is assumed in most Peak Oil analysis, as by Colin Campbell, for example – but again, this is disingenuous, as it ignores the scale of the problem. I still find this the most striking graph (based on Exxon figures, it’s a couple of years old now)

Essentially, the area under the black line can’t be bigger than the area of oil discovered. The rate of production WILL decrease. What figures like this don’t examine, of course, are the ‘alternative’ sources. Yet an honest analysis would account for those separately, in terms of net energy (EROEI). Otherwise we could simply include the worlds coal reserves in the equation – because they can be converted to liquid fuels too. (This analysis has been done, of course – a wholesale plan to replace oil with coal etc pushes the peak back by two decades. It’ll make global warming much worse as well, of course).

The petro-pessimists’ most forceful argument is that the Persian Gulf, officially home to most of the world’s oil reserves, is overrated…. So vast are the remaining reserves, and so well distributed are today’s producing areas, that a radical revision downwards—even in an OPEC country—does not mean a global peak is here.

This is just garbage. Total reserves aren’t the issue. The issue is rate of production, and despite all their words the Saudis a) aren’t able to increase production, and b) admit to serious declines (8%) in existing fields.

…The baleful thesis [of economic recession] arises from concerns both that a cliff lies beyond any peak in production and that alternatives to oil will not be available. If the world oil supply peaked one day and then fell away sharply, prices would indeed rocket, shortages and panic buying would wreak havoc and a global recession would ensue. But there are good reasons to think that a global peak, whenever it comes, need not lead to a collapse in output.

For one thing, the nightmare scenario of Ghawar suddenly peaking is not as grim as it first seems. When it peaks, the whole “super-giant” will not drop from 5m bpd to zero, because it is actually a network of inter-linked fields, some old and some newer. Experts say a decline would probably be gentler and prolonged. That would allow, indeed encourage, the Saudis to develop new fields to replace lost output. Saudi Arabia’s oil minister, Ali Naimi, points to an unexplored area on the Iraqi-Saudi border the size of California, and argues that such untapped resources could add 200 billion barrels to his country’s tally. This contains worries of its own—Saudi Arabia’s market share will grow dramatically as non-OPEC oil peaks, and with it the potential for mischief. But it helps to debunk claims of a sudden change.

The notion of a sharp global peak in production does not withstand scrutiny, either. CERA’s Peter Jackson points out that the price signals that would surely foreshadow any “peak” would encourage efficiency, promote new oil discoveries and speed investments in alternatives to oil. That, he reckons, means the metaphor of a peak is misleading: “The right picture is of an undulating plateau.”

This is fair enough, although it perhaps places too much trust in the free market – the position there is not as reassuring as the writer would have us believe (track the oil price futures market and see what they make of it!). Stuart Staniford reckons on a Slow Squeeze which is reassuring. But virtually everyone I read in the Peak Oil community is expecting an ‘undulating plateau’ – not least because of the lessening of demand through ‘demand destruction’.

What of the notion that oil scarcity will lead to economic disaster? Jerry Taylor and Peter Van Doren of the Cato Institute, an American think-tank, insist the key is to avoid the price controls and monetary-policy blunders of the sort that turned the 1970s oil shocks into economic disasters. Kenneth Rogoff, a Harvard professor and the former chief economist of the IMF, thinks concerns about peak oil are greatly overblown: “The oil market is highly developed, with worldwide trading and long-dated futures going out five to seven years. As oil production slows, prices will rise up and down the futures curve, stimulating new technology and conservation. We might be running low on $20 oil, but for $60 we have adequate oil supplies for decades to come.”

Again, this is ignoring EROEI.

The other worry of pessimists is that alternatives to oil simply cannot be brought online fast enough to compensate for oil’s imminent decline. If the peak were a cliff or if it arrived soon, this would certainly be true, since alternative fuels have only a tiny global market share today (though they are quite big in markets, such as ethanol-mad Brazil, that have favourable policies). But if the peak were to come after 2020 or 2030, as the International Energy Agency and other mainstream forecasters predict, then the rising tide of alternative fuels will help transform it into a plateau and ease the transition to life after oil….Alternative fuels will not become common overnight, as one veteran oilman acknowledges: “Given the capital-intensity of manufacturing alternatives, it’s now a race between hydrocarbon depletion and making fuel.” But the recent rise in oil prices has given investors confidence. As Peter Robertson, vice-chairman of Chevron, puts it, “Price is our friend here, because it has encouraged investment in new hydrocarbons and also the alternatives.” Unless the world sees another OPEC-engineered price collapse as it did in 1985 and 1998, GTL, tar sands, ethanol and other alternatives will become more economic by the day (see chart 2).

The sense of this depends upon the peak being far enough off that we have time to prepare – which is the gist of the Hirsch report, which argues that it will take twenty years of determined effort to switch fuels. The Economist is assuming that the USGS figures give that length of time. If they’re right, then we really don’t have anything to worry about. I don’t think they are though.

This is not to suggest that the big firms are retreating from their core business. …China also has deposits of heavy oil that would benefit from such an advanced approach. America, Canada and Venezuela have deposits of heavy hydrocarbons that surpass even the Saudi oil reserves in size. …All this explains why, in the words of Exxon Mobil, the oil production peak is unlikely “for decades to come”. Governments may decide to shift away from petroleum because of its nasty geopolitics or its contribution to global warming. But it is wrong to imagine the world’s addiction to oil will end soon, as a result of genuine scarcity.

There is another major factor which the Economist writer doesn’t address – rather surprisingly given their area of alleged expertise – which will exacerbate the problem and make the decline swifter (price rise larger) than the pure amount of oil would suggest. That relates to the exporting capacity of oil producer nations. Only a small number of oil producer nations are exporters; each also has an internal demand for oil and oil products. As the oil production itself declines, and the internal demand rises, the amount of oil available for export is being shrunk from two directions. This can be seen clearly in the case of Mexico, whose Cantarell oilfield is entering rapid decline. See the discussion here.

OK, summary of main flaws: dependence on over-optimistic USGS analysis, underestimate of difficulty in transition from oil to alternatives, complete ignorance of the principles of EROEI and the impact that this has on the mining of, eg, Canadian oil sands. Two serious factual flaws: denial of Deffeyes’ point (it’s too soon to tell if he’s wrong or not) and discussion of North Sea decline. On the whole, sloppy, biased, ill-informed reporting. Not what I would expect from the Economist. Makes me wonder whether those analyses which I read and enjoy in the Economist are any better informed.

UPDATE: ‘Heading Out’ gives a more sophisticated analysis here.