Solid, competent action-thriller. Director is obviously a 9/11 conspiracy theorist, and there are elements of the story that seem like a parable. 3.5/5

Monthly Archives: October 2008

New vehicle

We’ve reached a point where one vehicle is not enough – the kids need ferrying to their activities at the same time that I need to be able to move around the parishes swiftly (eg Sunday mornings) – and, not least for climate change reasons (that’s for Al), we didn’t want to get another car. So here you have me on a nice new(ish) Honda CG125. A very nice motorcycle, driven by someone who doesn’t quite know how to ride it yet; but soon, I shall become: a hairy biker!

TBTM20081024

Paris by night. (Click on the image to enlarge it if necessary).

TBTM20081023

Reasonable Atheism (30): some brief comments on the problem of suffering

It seems to me that there are two ways to understand the problem of suffering: the abstract question and the existential question.

The abstract question says that God has certain attributes – fully good, fully powerful, fully knowing – and that these three attributes are inconsistent with the presence of suffering in the world. (Stephen Law has a variation of this argument which states that these attributes are inconsistent with the degree of suffering in the world. I don’t find that this variation adds much to the argument; I’m with Alyosha Karamazov.)

My answer to the abstract question is to say that defining God’s attributes is a mistake. That is, we’re never in a position to give an overview of God’s attributes; in particular, attributing ‘goodness’ to God seems to presume too much, and I don’t think we’re in a position to judge whether God is good or not. To my mind God is ‘beyond good and evil’. In that assessment I view myself as being four-square in the mainstream mystical tradition of the church.

Yet, as I’ve tried to articulate before, these discussions, whilst of some interest in themselves, don’t actually address the core of the issue, which I see as existential. They are abstract and philosophical, and end up provoking more or less ‘so what?’ responses, rather like the decision about choosing one way of organising a library rather than another. The existential question is much more important, which is simply: how should one live in the face of suffering? In particular, in an environment where random events may render any person’s life-projects impossible, how are we to retain any sense in the meaningfulness of life?

Martha Nussbaum does an excellent job of describing the Ancient Greek response to this issue in her marvellous ‘The Fragility of Goodness’ – so answers to these questions by no means need to be Christian. Yet, obviously, the Christian faith also has an answer – indeed, I view the story of crucifixion and resurrection as the answer to Greek tragedy. The only perspective, in fact, that doesn’t seem to have an answer to the existential question is that of the humourless atheist – but then, they seem content to play in the abstract shallows, avoiding the muck and bloodiness of full-bodied life.

Stephen continues to believe that my answer to the problem of evil ‘does not exist’. I continue to believe that he doesn’t understand what I’m saying. He could persuade me differently by, eg, discussing Nussbaum’s work and his views on it.

One more thing about 9/11

James commented that the Popular Mechanics book does a thorough job of debunking the 9/11 conspiracy theories. It doesn’t, and David Ray Griffin does a very thorough debunking job on the Popular Mechanics book. I said this to James in the comments, which is worth bringing up front:

“If you don’t know then you obviously haven’t read it. I have read it and it’s crap. The site that I linked to does a much more coherent and thorough job in debunking the conspiracy theories, can I suggest you read that and become a little better informed?

I could easily be wrong about this – particularly the second as I’m not a physicist or civil engineer – but the pathetic level of argumentation put out by the Popular Mechanics book, mindlessly parroted by other ignoramuses, only encourages the speculation. The best thing about the site that I linked to is that it takes the conspiracy arguments seriously and takes the time to show why they are wrong – and I accept that most of them are wrong.”

In particular, after posting what I wrote yesterday, I watched this video at that site, which I think is very good, and, with the accompanying analysis, goes a long way to answer one of my core concerns about ‘the gravity of the question‘:

I remain sceptical about my scepticism because this whole issue provokes a lot of cognitive dissonance in me, and as I’ve said before I’d be tremendously grateful to be relieved of it.

TBTM20081022

I am absurdly pleased with this picture.

Today’s link: Every road leads you somewhere.

TBTE20081021

Two things that I don’t believe about 9/11

Gave a talk about the 9/11 truth movement to the ‘learning church’ here on Mersea, which has emboldened me to write something more on the blog. (In other words, I’m persuaded that I’m not completely bonkers, even if I remain a fan of Sarah Palin.) Hit ‘full post’ for text.

The first thing that I don’t believe about the official account of what happened on 9/11 is that Hani Hanjour was the pilot of the plane that hit the Pentagon. These are my reasons:

1. Hanjour was someone ‘who couldn’t fly at all’ according to the people who tried to train him (source). He was refused permission to rent a Cessna in August 2001 because his flying skills were so poor.

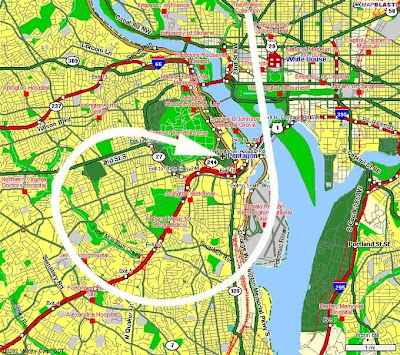

2. The path that flight 77 took in order to crash into the Pentagon was an extremely demanding one that would have taxed an experienced military pilot.

The pilot executed a 270 degree turn whilst simultaneously dropping by 7,000 feet, before levelling off to fly just above ground level in order to hit the Pentagon’s ground floor.

3. This flight path took Hanjour past the White House, past the obvious and immediate wall of the Pentagon (where Rumsfeld’s office was based) and into the only wall of the Pentagon that had – purely coincidentally – recently been reinforced to withstand an impact.

The second thing that I don’t believe about the official story of 9/11 is that the three skyscrapers toppled that day were brought down by fire. These are my reasons:

1. No steel skyscrapers either before or since have collapsed as a result of fire. This includes skyscrapers where the fires burnt hotter, for longer, over a wider area than on 9/11. Fire damage looks like this:

This is the Windsor tower in Madrid, which caught fire in February 2005. Despite having intense fires burning for many hours it did not collapse – indeed, the building functioned in exactly the way anticipated by the relevant fire regulations.

2. The collapse of the three skyscrapers on 9/11 exhibited a large number of features that are inconsistent with fire damage. These include

- sudden onset,

- symmetrical collapse,

- vertical collapse,

- total collapse,

- at virtually free-fall speed,

- within substantially its own footprint.

3. There is an extremely well understood means of collapsing buildings which produces these effects (controlled demolition). If the controlled demolition hypothesis is ruled out then it is proven that the laws of physics can be overcome in the right circumstances (eg conservation of momentum).

I don’t know what this means in a wider sense as I find most of the more plausibly worked out conspiracy theories incredible. Yet as Mr Holmes once said, once the impossible has been ruled out, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the case.

For an alternative view, go here.

TBTM20081021

Killed for being a Christian.

Not a headline I ever expected the Independent to ever lead with – the times they are a’changin.