Not sure about this one. Anything which opens with a few minutes of half-accurate exposition of Wittgenstein has to be good in my book but… I watched it with my mother-in-law who described it as flat in pacing and like a TV movie. Couldn’t disagree really. 3/5

Monthly Archives: August 2010

What I think about the Bible, reposted

First posted in February 2007; reposted as an answer to Paul’s meme

The I-Monk interviewed himself (go read it here, it’s very interesting) and I thought I’d steal the “Ten Questions About the Bible”

1. State briefly what you believe about the Bible.

Scripture contains all things necessary for salvation; it witnesses to Christ – and in Christ is eternal life. (John 5.39)

2. How is the Bible inspired?

‘God-breathed’ – God is the subject of the text. Also: at each stage of the process: composition; collation; reading.

3. So is the book of Judges inspired, or only the Gospels?

At what point does the valley become the mountain? God was present at the time of the Judges, the book of Judges records what the community understood of Him at that time. The understanding of the gospel writers was significantly in advance of that.

4. How is the Bible authoritative?

The Bible carries the authority given to it by the church – so, for the Church of England, it is the controlling authority, which is best understood with the help of tradition and reason.

5. Is the Bible a human book?

All books are human. There is a docetic suspicion lurking behind this question – an assumption that because something is human it cannot also bear the stamp of divinity.

6. Are there aspects of the Bible that are not divine?

All of it. And none of it. The Spirit, being the relational part of the Trinity, is what is needed for anything to become divine. It is not ‘inertly’ divine (that seems more like the Islamic understanding of the Koran).

7. Why do you call the Bible a conversation?

Because there are lots of competing voices in it. The way to read the Bible, the way for it to help you to walk in the Christian way, is to listen to the different voices and get a handle on the common subject – then you are in a position to take the conversation forward in your own life.

8. What do you believe about canonization?

Canonisation is the process by which the church discriminates between those writings which give life and those which destroy life. I trust its discernment. I also don’t see any canon as final; I think the church universal has the capacity to amend the canon, either positively or negatively.

9. Do you reject the inspiration of some books?

No.

10. Anything else you want to say?

Inerrancy is never claimed by the Bible. It is an alien importation from the doctrines of men and represents a crippling disease in the Body of Christ.

11. is your theology “inconsistent?”

God knows.

Even if it’s not explicitly a meme, I’d be very interested in other people’s answers to these questions.

(Picture taken last week; chosen because you can’t sail on a reflection, even if a reflection can tell you an awful lot about the original…)

Rev.isited

This is by way of a response to Jon who thinks I’m too harsh on Adam Smallbone and who argues “Smallbone’s ‘I’m tired of having to tell people what they want to hear all the time’ is something that I would guess most of us think at some stage in our ministry. Moments like those have been the basis for much of the comedy in the series and, in my experience at least, seem an authentic reflection on an aspect of being in ministry. In the context of the story told in the final episode, that comment was then deliberately undercut by the writers in the denouement to the episode where he says exactly what his dying parishioner wants and needs to hear and this is restorative both for the parishioner and himself.”

Trouble is, if that is the truth – and yes, all good art is open to multiple interepretation – but if that is the truth then, for me, the ending is denuded of all value. Let me explain.

I read the climax of the series, when Smallbone is collected by the police and taken off to do his proper work, as a moment of anagnorisis. In other words, in the midst of his drunken gropings, the overflow of self-pity and self-hatred, Smallbone is recalled to his essential vocation, a vocation expressed in ministering with truth and dignity in a sacramental fashion. In other words, there is a break with what has gone before – which, in retrospect, is seen unfavourably. That had great power for me – it is why I liked it.

If, however, Jon’s analysis is true, and Smallbone is still saying ‘exactly what his dying parishioner wants and needs to hear’ then there is a consistency between Smallbone’s behaviour leading up to this moment and what he then does. In other words, there is no anagnorisis, there is no crisis, there is no growth in self-knowledge. How dull!

The trouble is that I really could believe Jon’s analysis of the writers’ intention to be true. That is, I found the ending so wonderful because it undercut what had gone before, not because it was consistent with what had gone before.

Something else needs to be touched on.

The problem is that ‘saying what people want to hear’ is a consistent part of Smallbone’s nature, and it ties in with what I see as a lack of character. A previous moment that I felt was telling was when Smallbone half-apologises to his wife that they have never had children, and the wife responds that she already has one, ie him! Perhaps they should have called the character ‘Adam No-Backbone’ instead.

There is all the difference in the world between refraining from speaking the truth – out of pastoral concern and sensitivity to kairos, say – and speaking what people want to hear. The one is a prudent forebearance that keeps at least one eye on the main purpose, the other is a rootless drifting in the currents of the world. It is because Smallbone had seemed to be so much of the latter kind that I found the ending so wonderful a contrast.

I would not wish to argue, either, that this is a matter of strength of character. Indeed, that is to perpetuate the most fundamental theological error in the programme. God is more than happy to make use of weak vessels to accomplish his own ends, indeed, as St Paul tells us, this is in some ways the essential point in being a Christian. Again, this is what I found so wonderful and true about the ending – a weak man being the means of divine grace.

The trouble with Smallbone is that he lacked a place to stand outside of himself, somewhere that is not comprised of (and compromised by) his own narcissism. He lacked, so it seemed to me, any sense of the otherness of God, of that power greater than himself within which he found his own true calling and nature, which loved him and enabled him to be himself – to precisely not be a false self, presenting what other people wanted to hear. I don’t think it a coincidence that there was so little exploration of worship in the programme – perhaps they couldn’t, as it was a comedy – yet without that, any true presentation of priesthood collapses. I often felt that the programme could have been changed into a non-religious context without any serious alterations of character being required – Smallbone could easily have been a social worker or government bureaucrat, and much of the comedy would have remained.

To put it succinctly, Smallbone had no fear of God in him. That is why I shall continue to see him as the construct of the secular, liberal elite – they have no understanding of the fear of God, no sense of it as a living (and life-giving) reality – and their presentation of the faith shares that failing. They don’t understand it, therefore it doesn’t exist – other than as a quaint delusion shared by the uneducated or mentally deficient. Smallbone is a nice guy, doing his best.

Forgive me, but I believe that there is more to being a Rev. than that.

The collapse of civilisations (part one)

A courier article, based on my original Tainter review

Pretty much every civilisation that has ever existed has come to an end (we can argue about China another time). Our civilisation will be no different. There has, as you might expect, been a fair bit of academic research into why this is the case. What I’d like to do in the next few articles is describe how this collapse might be understood, first in general terms with a book review; then thinking more locally, in terms of the UK and Mersea itself; finally thinking about what sort of response we might make.

The seminal work in this field is ‘The Collapse of Complex Civilisations’ by Joseph Tainter. Tainter’s work was originally published in 1988 and has the feel of a work which is establishing a new field of study. Tainter is concerned to explore what ‘collapse’ means, when applied to a society; how collapse happens; and, in the conclusion, to draw some possible lessons for our present situation. The first chapter is a swift survey of eighteen historical examples of collapsed societies around the world, from the Harappans to the Hohokams. This serves to introduce the field that Tainter wishes to study, and also indicates the absence of rigorous empirical investigation. This is the cue for Tainter to begin his systematic analysis. He outlines what is meant by ‘collapse’, describing it as “a matter of rapid substantial decline in an established level of complexity. A society that has collapsed is suddenly smaller, less differentiated and heterogeneous, and characterised by fewer specialised parts…” Then in chapter three, Tainter surveys the explanations commonly given for why a particular society collapses, finding them all more or less deficient, and saving an especial scorn for ‘mystical explanations’ (eg Spengler or Toynbee), about which he writes: “Mystical explanations fail totally to account scientifically for collapse. They are crippled by reliance on a biological growth analogy, by value judgements, and by explanation by reference to intangibles.” In the course of this chapter he also gives a resounding declaration of the benefit of excluding value-judgements: “A scholar trained in anthropology learns early on that such valuations are scientifically inadmissible, detrimental to the cause of understanding, intellectually indefensible, and simply unfair”.

Tainter then takes the best existing explanation for collapse (economic) and proceeds to develop a hypothesis to explain why complex societies might suddenly shift from a more complex to a less complex state. His thesis can be concisely stated: increasing complexity gives rise to diminishing marginal returns on investment; when those returns become negative, the society has a progressively diminishing capacity to withstand stress, and is vulnerable to collapse.

Essentially at point C3 there is no benefit from the increase of complexity (C3-C1) – hence the collapse from C3 to C1.

This thesis is built upon four working assumptions:

– human societies are problem-solving organisations;

– sociopolitical systems require energy for their maintenance;

– increased complexity carries with it increased costs per capita; and

– investment in sociopolitical complexity as a problem-solving response often reaches a point of declining marginal returns.

What happens is that, as a complex society initially develops, there is a very high return on investment in complexity – the resources made available through that adoption of complexity are far higher than are used up through the complex organisation itself. However, over time, the ‘low hanging fruit’ are used up, and for every increase in complexity there is a lower and lower resource return until there comes a point where simply maintaining the existing complexity has a negative impact upon available resources – in other words, the resources are more efficiently deployed through a less complex system.

Tainter gives a number of different specific and small-scale examples where this decline in marginal returns applies, for example in terms of the return on research and development investment, or medical research, but his next chapter applies the theory to understanding three different examples of collapse. The most telling example, to my mind, was that of the farmers in the latter stages of the Western Roman Empire, who were taxed more and more heavily in order to maintain the apparatus of the Roman state, and who eventually welcomed the barbarian invasions as a release from what had become Roman oppression. A Roman structure of high complexity had been viable for as long as there were increasing resources made available – and this was accomplished through conquest. However, once the limits of conquest were reached (either with the German tribes, whose relative poverty made their conquest uneconomic, or through coming up against another Empire strong enough to resist Rome, eg the Parthian) then that model of development became untenable. The accumulated resources available to Rome were drawn down, its capacity to absorb shocks to the system was eroded, and thus the collapse of that form of complexity became a matter of time. As Tainter writes, “Once a complex society enters the stage of declining marginal returns, collapse becomes a mathematical likelihood, requiring little more than sufficient passage of time to make probable an insurmountable calamity”. As a complex society enters into this terminal phase, the advantages to retreating to a previously existing level of complexity become more and more obvious, and local communities start to shift their allegiance: “…a society reaches a state where the benefits available for a level of investment are no higher than those available for some lower level…Complexity at such a point is decidedly not advantageous, and the society is in danger of collapse from decomposition or external threat”.

Next time, I’ll start to link these generalities with the specifics that we face in England generally, and on Mersea in particular.

Clouds and silver linings

Cloud: getting a puncture on the back wheel of my motorbike on my way back from Colchester, 5 miles from home, and having to push it home.

Silver linings: all the lovely parishioners who stopped to give me practical and moral support

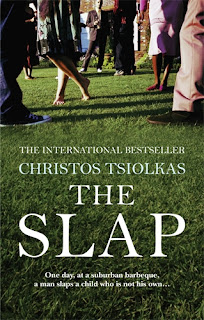

The Slap – Christos Tsiolkas

Jane Austen, with added pornography.

Let me expand slightly on that: a very interesting portrait of a small group of middle-aged, middle-class parents, and the consequences upon their lives when one of their number slaps the child of another. I might have wished for a little less crudity, but it was an absorbing read, and it raises some important issues into the light. Recommended.

Rev.

Two brilliant things about that latest and last episode of Rev, which was watched late by me:

– the ending,

– the portrayal of what it is to be a fed up vicar, flopped on the sofa watching rubbish TV with beer in hand (‘I feel like a remnant of an illusion that people used to believe in’ – great line).

Could relate to both of those things.

What I really got frustrated with, however, was the continued lack of authenticity in the portrayal of the vocation, summed up when Smallbone says ‘I’m tired of having to tell people what they want to hear all the time’. Throughout the series he seemed to have no moral centre, no anchor – a representation of what the liberal elites think about faith. Gah!

I’ve enjoyed the programme – and I’d watch another series if they made one – but I still long for a portrayal of a priest that isn’t filtered through a secular mindset.

Inception

A very clever film, and very enjoyable, and even has an emotional punch, but… not sure. There’s something not quite perfect about it (might just be that I don’t like Leo very much). Perhaps the overall balance wasn’t completely right. Not enough emotional substance? Perhaps I’m just being too picky – it’s certainly a cut above most films.

It was also not as confusing as I had thought it was going to be, though I’d kept clear of various reviews so as not to prejudge things, which probably helped. I look forward to watching it again when it comes out on DVD.

I think – in sum – it’s a contrast between two things for me – the end shot (reproduced above) which reminded me so much of the end of Tarkovsky’s Mirror (no higher praise) with wonderful ambivalence – and the distraction of some of the action sequences (some were phenomenal, but the snow-battle was a distraction I feel). Hmmm. Still thinking about it – must be a good sign.

4.5/5

PS I think this review says it.

Three factors

A bit of a riff on my ‘hate it here’ post (NB newish readers should probably see this post for a bit more on the ‘hate’ part).

I’m not very good at discerning the timing of events – that is, I underestimate the amount of inertia in the system, and things happen much more slowly than might be expected on abstract logical grounds. That said, these are things that I see being important over the next fifteen years or so:

– first, the whole question of Islam/terrorism, and the likely political and strategic conflicts and realignments that might come about in the Middle East;

– second, the ongoing financial crisis and deflation, leading to (probably) a shift in economic power to the East;

– thirdly, crashing into resource limits, especially the peaking of the oil supply.

Now all of these three are going to interact in multiple and unpredictable ways. What I’m pretty sure about, however, is that coming out on the other side, we will be in a very different place. Which is why a lot of the prognostications that depend upon more or less ‘business as usual’ seem rather unreal to me.