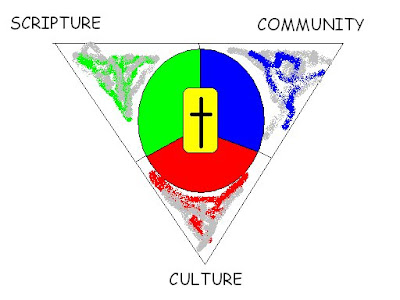

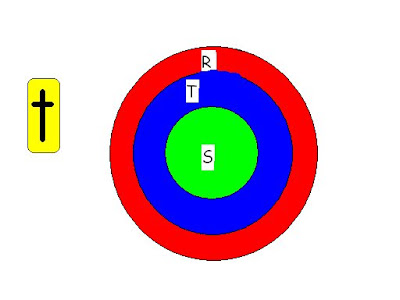

I didn’t succeed in recording the first part of my Learning Church sequence on evangelicalism, which is rather a shame. I’m going to try and write up my talk, in two parts. The first one about where I personally am coming from and why I have the perspective that I do. The second one will be about my triangle and how I use it to interpret goings-on in the Anglican Communion.

So you could call this my “testimony”, if you were so inclined.

I grew up in what might be considered a typically Anglican family – there was belief but not a great deal of belonging. As a family we went to church three or four times a year (always at Christmas and Easter) and the Bible, stories of faith and prayer were a part – not a huge part – but definitely a part of the context of my early life. I have a distinct memory of when I was about seven years old of starting to read the Bible from the beginning – I think I got as far as the first genealogy! There was an occasional attendance at Sunday School, but no great commitment to it. On one side of the family was an active Anglican commitment (one grandparent being a church warden for some fifty years); on the other side a much more non-conformist ‘chapel’ heritage, with a strong commitment to social activism. It’s interesting seeing those two strands wrestle within me every so often.

At the age of eleven I was sent off to Boarding School. This was a Christian foundation and the school assemblies every morning were embedded in Christian worship, including the singing of a hymn every day; in addition there was a full church service every Sunday morning, in the chapel, attendance at which was compulsory. In my second year at boarding school I remember a conversation with a class mate about Gandhi, and whether he was bound for hell or not. As I took my friend’s understanding of Christianity to be ‘the truth’, and as I couldn’t accept the justice of Gandhi being doomed to eternal torment, I became an atheist. At first not a very active one, but over time, more and more determined. When I was about fourteen some Jehovah’s Witnesses came to visit and left a tract detailing their opposition to the theory of evolution. I read the tract; thought ‘this is interesting’, and decided to explore further. I wanted to hear from an alternative point of view so I purchased Richard Dawkins’ ‘The Blind Watchmaker’. This I found much more persuasive, and, along with the acceptance of evolution I accepted his general antagonism towards religious belief.

In essence the rejection of Christianity was driven by two things: a sense that it was unjust, and a sense that it was untrue. However, being at boarding school meant that I continued to be fed the diet of worship, including the singing of hymns, recitation of set prayers, and listening to sermons on a regular basis. I am certain that this has strongly shaped many of my attitudes to liturgy today, both positively and negatively.

My antagonism towards Christian belief manifested itself as antagonism towards religious believers, ie my classmates, including the very same classmate with whom I had had that original conversation about Gandhi. The trouble with me, however, was that I wouldn’t let things alone, and whenever the opportunity arose I would engage vigorously in discussion about the truth or otherwise of Christian doctrine. The real truth was that I was obsessed with God! (I still am really.)

When I was seventeen there were a couple of knocks to my sense of self and sense of purpose, one of the more significant being a rejection from Oxford University. I had a distinct sense that I was going to end up at Oxford, so, whilst ‘banking’ an offer from the LSE I resolved to try again in the context of a year out. What actually happened over that year, however, was a more general ‘drift’. Most of my ambitions had either been realised or put on hold and I had the opportunity to explore and read more widely. Most crucially, whilst thinking through my re-application for Oxford I came across a description of the Philosophy and Theology course, written by one of the students, which was headlined ‘You don’t have to be religious to work here’. This caught my interest, and the more I explored it, the more I thought ‘this is actually what I want to study’.

My motivation was not entirely honourable. I read ‘The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail’ at around this time, and was intrigued by the thought that modern scholarship provided much more heavyweight tools for attacking Christians with! Following some pleasing A Level results I then reapplied to Oxford and the experience could not have been more different than before – all the doors seemed to open up before me, and I got my place, to go up in the Autumn of 1989.

That summer, with my future settled, and after working in Colchester doing various exciting and exotic jobs(!) I spent three months travelling around the United States and Canada with a friend. I had recently read Robert Pirsig’s ‘Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance’ for the first time, and that had a huge impact upon me. I had always had a strongly ‘mystical’ streak, even in my aggressive atheism, and I devoured a lot of material on the occult and New Age spirituality. Pirsig’s account of Quality made a tremendous amount of sense to me – it still does – but it was probably the most important factor in dismantling the aggressive atheism that I had imbibed from Dawkins.

So I went up to Oxford, all the chips on my shoulder still intact, and waded in to my tutorials with my prejudices. Which didn’t last for very long. Very gently – astonishingly gently really – my principal tutor, who was the College chaplain, slowly took apart all of my beliefs about what Christianity actually was, and demonstrated, both through his teaching and example, that Christianity was intellectually credible. You didn’t have to leave your brain behind when you walked in the door. Essentially, what I had been rejecting as Christianity I would now recognise as fundamentalism, and there is the world of difference between the two.

However, this change in my attitude was not enough to bring me to a form of belief. Logic and reason can do many things but our foundational commitments are not borne on either, they’re much too important for that. What triggered the change was a religious experience. I was on my own at home in the August of 1990 and reading the book ‘Green Christianity’ by Tim Cooper. I remember vehemently disagreeing with him about God, and thinking ‘but God’s not like that!’. And I caught myself thinking that, and realising that I was arguing from a position of accepting God – in other words I realised that I did believe in God – and at this point my head exploded. I fell to my knees and my sight was wiped out with white brightness. Two things in particular erupted into my consciousness. The first was about the overwhelming priority of love. That love was, in the strictest scientific sense, the fundamental force governing the universe; that I loved God – and always had – and that I was loved by God; that love literally made the world go round. The second is caught in the phrase ‘become who you are’. There was an astonishing degree of affirmation involved – an affirmation I still draw on today – and I was on an emotional high for quite some time – weeks – afterwards. This was the foundation of my vocation.

Well I returned to Oxford a little chastened, in that a lot of the positions I had adopted I now repudiated, and I largely withdrew from active involvement in many wider endeavours. I had received the wound of knowledge and I needed to dig down and work out where that wound had come from. So I actively pursued my studies, and explored Christianity, and slowly more and more pieces fell into place. I was confirmed in the Church of England one year later – as someone who still had lots of doubts, and was undoubtedly ‘unorthodox’ in belief, but someone who was also committed to this path.

In 1992 I left Oxford and went to London, working for the Civil Service. Church attendance fell away during this time, although my own personal explorations of the faith continued actively. The next really significant breakthrough occurred in 1995, when, as a result of my wider personal life becoming rather complicated (see here) I had another religious epiphany. This one was not so positive, in that God made it clear to me that I was embarked upon the road to hell. He also made it clear that I was called to the priesthood; specifically I was given a vision of celebrating the Eucharist – THIS was what I was called to do. I resisted for as long as I was able to – about two days – because the thought of becoming a vicar was anathema to me. To me a vicar was a figure of fun, an ineffectual wimp tossed hither and thither by cultural forces beyond his comprehension, an intellectually vacant space. I gave in, of course. (In retrospect I’m sure that reading the Susan Howatch novels in the months preceding laid a foundation for this; ignoring the literary merit I think they’re pretty sound theologically).

Once more my life changed course, but this time it was through a commitment not simply to exploring the faith in an intellectual sense, but through starting to change my life and habits away from ‘the works of darkness’ and putting on the armour of light. I became actively involved in the church I had recently begun to attend and put out feelers concerning potential ordination. I left the Civil Service one year later and worked as the school caretaker in the church school, joining in the Daily Office and generally getting embedded in the church life.

I also started up a Master’s degree at Heythrop, as this seemed to be a part of the vocation. My intellectual gifts had helped open up the path of faith for me in the first place, and it seemed natural that they would be a part of the vocation itself. In this I was encouraged and affirmed by the church hierarchy. This was a mistake. The first fruits of the mistake came at the end of the first year when I received a mark in an examination on Wittgenstein which was a) by far the worst mark I had ever received in such an examination, b) on the basis of what was, without doubt, the best work I had ever done, and c) which caused consternation to my tutor and fellow students (in other words, it wasn’t just me who thought the mark surpassing strange). Despite their best efforts to have the work re-marked the college refused and the papers were later destroyed. I later discovered, through a friend, that the principal examiner for the paper was not familiar with one of the key works on the topic (Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer). In my various answers I had adopted an extremely allusive style, with a great many references to Wittgenstein’s writings on religion, which someone familiar with the field would have recognised instantly. However, for someone not familiar with the writings, they would undoubtedly have appeared strange and idiosyncratic – hence the low mark. I abandoned the MA in bewilderment, but trusted that God was in charge.

I was accepted for training for ordination, and after a tour around different theological colleges – I was keen to go to an evangelical college like Ridley, but my Bishop talked me out of it(!) – I went up to Westcott where my training was a combination of vocational work and a PhD. At first I flourished – there is an important part of me that revels in academic life – but in the second term the academic side completely fell apart. I realised that I had a profoundly different approach to the role of academic theology in the life of the Spirit, and that the essential thing for me was to be formed as a priest, not trained as an academic. I abandoned the PhD but then had a frankly awful time at Westcott as the institution sought to ensure that my academic training was sufficient, while I was spiritually straining in a completely different direction. I also met my wife at this time – in church – and after an extremely rapid courtship we got married. All of this rather overwhelmed me and with the benefit of hindsight I can see that I was deeply depressed throughout my second year there.

I then returned to London where I pursued my curacy in the East End. This was, on the whole, a very positive experience, a good grounding for ministry, but the last year of this was intense and draining, and involved the sudden death of my father (for more in this see here). Once more I was in a state of bewilderment, but it became clear that I needed to take time out. Through a legacy, my wife and I – and a newborn son – were able to spend a year on sabbatical in Alnwick, Northumberland, surely one of the most beautiful places on God’s green earth. This was a year in which I was able to catch up with myself, and digest all that had happened. In particular this was a time when I was able to come to terms properly with the collapse of all my academic pretensions and ambitions. I gave very serious consideration to pursuing a PhD at Durham, but in the end it became clear that parish ministry was the right next step. I still have a distinct academic ‘itch’, but I am much more relaxed about whether it will end up being scratched or not. In particular it is much more clear to me that the role of the intelligence is in the service of the church and whilst it may be possible for that service to overlap with the needs of the academic institutions there are definite times when there is conflict. And my calling is to serve the Body – the cloister not the academy.

All this was prior to Mersea. When I saw the post advertised I immediately felt ‘this is it’. I withdrew from another post that I was exploring and, as had happened occasionally before, felt that all the doors were opening up. It’s a bit like cracking the combination of a safe – slowly all the tumblers fall into place, things get turned one way or another and then – it all opens up.

Now since my rejection of fundamentalism at the age of 12; and then my intellectual explorations of the faith through University; and then my immersion in serious religion of the Anglo-Catholic sort through my church sponsorship, training and curacy, I had never had to deal all that seriously with evangelicals. They represented a sort of ‘here there be dragons’ element in my mental map, and, in particular, I found it hard to distinguish them from fundamentalists and other lunatics. Yet here on Mersea I was immediately immersed in a context where there were a great many evangelicals, and even more on the way, especially amongst my colleagues. So I have been forced to engage with what evangelicalism is and means. I am an outsider to evangelicalism; it would be a mistake to class me AS an evangelical; but I find, after a number of years getting to know it as an ideology and getting to know evangelicals as individuals, that I am much more sympathetic to it than I would ever have expected.

That is the context in which I shall be exploring evangelicalism from an outsider’s perspective. As someone convinced of the reality of God and the overwhelming love of God; one who is committed to a historically grounded orthodox faith; and one who has a growing sympathy with the evangelical tradition – but also as someone who remains an outsider.